Predicting 30-day pneumonia readmissions using electronic health record data

BACKGROUND

Readmissions after hospitalization for pneumonia are common, but the few risk-prediction models have poor to modest predictive ability. Data routinely collected in the electronic health record (EHR) may improve prediction.

OBJECTIVE

To develop pneumonia-specific readmission risk-prediction models using EHR data from the first day and from the entire hospital stay (“full stay”).

DESIGN

Observational cohort study using stepwise-backward selection and cross-validation.

SUBJECTS

Consecutive pneumonia hospitalizations from 6 diverse hospitals in north Texas from 2009-2010.

MEASURES

All-cause nonelective 30-day readmissions, ascertained from 75 regional hospitals.

RESULTS

Of 1463 patients, 13.6% were readmitted. The first-day pneumonia-specific model included sociodemographic factors, prior hospitalizations, thrombocytosis, and a modified pneumonia severity index; the full-stay model included disposition status, vital sign instabilities on discharge, and an updated pneumonia severity index calculated using values from the day of discharge as additional predictors. The full-stay pneumonia-specific model outperformed the first-day model (C statistic 0.731 vs 0.695; P = 0.02; net reclassification index = 0.08). Compared to a validated multi-condition readmission model, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services pneumonia model, and 2 commonly used pneumonia severity of illness scores, the full-stay pneumonia-specific model had better discrimination (C statistic range 0.604-0.681; P < 0.01 for all comparisons), predicted a broader range of risk, and better reclassified individuals by their true risk (net reclassification index range, 0.09-0.18).

CONCLUSIONS

EHR data collected from the entire hospitalization can accurately predict readmission risk among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. This approach outperforms a first-day pneumonia-specific model, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services pneumonia model, and 2 commonly used pneumonia severity of illness scores. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:209-216. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

Of 1463 index hospitalizations (Supplemental Figure 1), the 30-day all-cause readmission rate was 13.6%. Individuals with a 30-day readmission had markedly different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics compared to those not readmitted (Table 1; see Supplemental Table 2 for additional clinical characteristics).

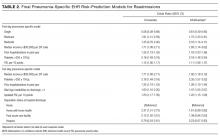

Derivation, Validation, and Performance of the Pneumonia-Specific Readmission Risk-Prediction Models

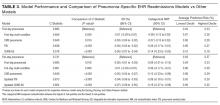

The final first-day pneumonia-specific EHR model included 7 variables, including sociodemographic characteristics; prior hospitalizations; thrombocytosis, and PSI (Table 2). The first-day pneumonia-specific model had adequate discrimination (C statistic, 0.695; optimism-corrected C statistic 0.675, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.667-0.685; Table 3). It also effectively stratified individuals across a broad range of risk (average predicted decile of risk ranged from 4% to 33%; Table 3) and was well calibrated (Supplemental Table 3).

The final full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR readmission model included 8 predictors, including 3 variables from the first-day model (median income, thrombocytosis, and prior hospitalizations; Table 2). The full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR model also included vital sign instabilities on discharge, updated PSI, and disposition status (ie, being discharged with home health or to a post-acute care facility was associated with greater odds of readmission, and hospice with lower odds). The full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR model had good discrimination (C statistic, 0.731; optimism-corrected C statistic, 0.714; 95% CI, 0.706-0.720), and stratified individuals across a broad range of risk (average predicted decile of risk ranged from 3% to 37%; Table 3), and was also well calibrated (Supplemental Table 3).

First-Day Pneumonia-Specific EHR Model vs First-Day Multi-Condition EHR Model

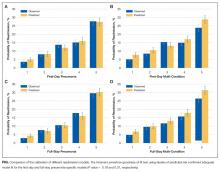

The first-day pneumonia-specific EHR model outperformed the first-day multi-condition EHR model with better discrimination (P = 0.029) and more correctly classified individuals in the top 2 highest risk quintiles vs the bottom 3 risk quintiles (Table 3, Supplemental Table 4, and Supplemental Figure 2A). With respect to calibration, the first-day multi-condition EHR model overestimated risk among the highest quintile risk group compared to the first-day pneumonia-specific EHR model (Figure 1A, 1B).

Full-Stay Pneumonia-Specific EHR Model vs Other Models

The full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR model comparatively outperformed the corresponding full-stay multi-condition EHR model, as well as the first-day pneumonia-specific EHR model, the CMS pneumonia model, the updated PSI, and the updated CURB-65 (Table 3, Supplemental Table 5, Supplemental Table 6, and Supplemental Figures 2B and 2C). Compared to the full-stay multi-condition and first-day pneumonia-specific EHR models, the full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR model had better discrimination, better reclassification (NRI, 0.09 and 0.08, respectively), and was able to stratify individuals across a broader range of readmission risk (Table 3). It also had better calibration in the highest quintile risk group compared to the full-stay multi-condition EHR model (Figure 1C and 1D).

Updated vs First-Day Modified PSI and CURB-65 Scores

The updated PSI was more strongly predictive of readmission than the PSI calculated on the day of admission (Wald test, 9.83; P = 0.002). Each 10-point increase in the updated PSI was associated with a 22% increased odds of readmission vs an 11% increase for the PSI calculated upon admission (Table 2). The improved predictive ability of the updated PSI and CURB-65 scores was also reflected in the superior discrimination and calibration vs the respective first-day pneumonia severity of illness scores (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Using routinely available EHR data from 6 diverse hospitals, we developed 2 pneumonia-specific readmission risk-prediction models that aimed to allow hospitals to identify patients hospitalized with pneumonia at high risk for readmission. Overall, we found that a pneumonia-specific model using EHR data from the entire hospitalization outperformed all other models—including the first-day pneumonia-specific model using data present only on admission, our own multi-condition EHR models, and the CMS pneumonia model based on administrative claims data—in all aspects of model performance (discrimination, calibration, and reclassification). We found that socioeconomic status, prior hospitalizations, thrombocytosis, and measures of clinical severity and stability were important predictors of 30-day all-cause readmissions among patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Additionally, an updated discharge PSI score was a stronger independent predictor of readmissions compared to the PSI score calculated upon admission; and inclusion of the updated PSI in our full-stay pneumonia model led to improved prediction of 30-day readmissions.

The marked improvement in performance of the full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR model compared to the first-day pneumonia-specific model suggests that clinical stability and trajectory during hospitalization (as modeled through disposition status, updated PSI, and vital sign instabilities at discharge) are important predictors of 30-day readmission among patients hospitalized for pneumonia, which was not the case for our EHR-based multi-condition models.19 With the inclusion of these measures, the full-stay pneumonia-specific model correctly reclassified an additional 8% of patients according to their true risk compared to the first-day pneumonia-specific model. One implication of these findings is that hospitals interested in targeting their highest risk individuals with pneumonia for transitional care interventions could do so using the first-day pneumonia-specific EHR model and could refine their targeted strategy at the time of discharge by using the full-stay pneumonia model. This staged risk-prediction strategy would enable hospitals to initiate transitional care interventions for high-risk individuals in the inpatient setting (ie, patient education).7 Then, hospitals could enroll both persistent and newly identified high-risk individuals for outpatient interventions (ie, follow-up telephone call) in the immediate post-discharge period, an interval characterized by heightened vulnerability for adverse events,28 based on patients’ illness severity and stability at discharge. This approach can be implemented by hospitals by building these risk-prediction models directly into the EHR, or by extracting EHR data in near real time as our group has done successfully for heart failure.7

Another key implication of our study is that, for pneumonia, a disease-specific modeling approach has better predictive ability than using a multi-condition model. Compared to multi-condition models, the first-day and full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR models correctly reclassified an additional 6% and 9% of patients, respectively. Thus, hospitals interested in identifying the highest risk patients with pneumonia for targeted interventions should do so using the disease-specific models, if the costs and resources of doing so are within reach of the healthcare system.

An additional novel finding of our study is the added value of an updated PSI for predicting adverse events. Studies of pneumonia severity of illness scores have calculated the PSI and CURB-65 scores using data present only on admission.16,24 While our study also confirms that the PSI calculated upon admission is a significant predictor of readmission,23,29 this study extends this work by showing that an updated PSI score calculated at the time of discharge is an even stronger predictor for readmission, and its inclusion in the model significantly improves risk stratification and prognostication.

Our study was noteworthy for several strengths. First, we used data from a common EHR system, thus potentially allowing for the implementation of the pneumonia-specific models in real time across a number of hospitals. The use of routinely collected data for risk-prediction modeling makes this approach scalable and sustainable, because it obviates the need for burdensome data collection and entry. Second, to our knowledge, this is the first study to measure the additive influence of illness severity and stability at discharge on the readmission risk among patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Third, our study population was derived from 6 hospitals diverse in payer status, age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Fourth, our models are less likely to be overfit to the idiosyncrasies of our data given that several predictors included in our final pneumonia-specific models have been associated with readmission in this population, including marital status,13,30 income,11,31 prior hospitalizations,11,13 thrombocytosis,32-34 and vital sign instabilities on discharge.17 Lastly, the discrimination of the CMS pneumonia model in our cohort (C statistic, 0.64) closely matched the discrimination observed in 4 independent cohorts (C statistic, 0.63), suggesting adequate generalizability of our study setting and population.10,12

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, generalizability to other regions beyond north Texas is unknown. Second, although we included a diverse cohort of safety net, community, teaching, and nonteaching hospitals, the pneumonia-specific models were not externally validated in a separate cohort, which may lead to more optimistic estimates of model performance. Third, PSI and CURB-65 scores were modified to use diagnostic codes for altered mental status and pleural effusion, and omitted nursing home residence. Thus, the independent associations for the PSI and CURB-65 scores and their predictive ability are likely attenuated. Fourth, we were unable to include data on medications (antibiotics and steroid use) and outpatient visits, which may influence readmission risk.2,9,13,35-40 Fifth, we included only the first pneumonia hospitalization per patient in this study. Had we included multiple hospitalizations per patient, we anticipate better model performance for the 2 pneumonia-specific EHR models since prior hospitalization was a robust predictor of readmission.

In conclusion, the full-stay pneumonia-specific EHR readmission risk-prediction model outperformed the first-day pneumonia-specific model, multi-condition EHR models, and the CMS pneumonia model. This suggests that: measures of clinical severity and stability at the time of discharge are important predictors for identifying patients at highest risk for readmission; and that EHR data routinely collected for clinical practice can be used to accurately predict risk of readmission among patients hospitalized for pneumonia.