Detecting sepsis: Are two opinions better than one?

The diagnosis of sepsis requires that objective criteria be met with a corresponding subjective suspicion of infection. We conducted a study to characterize the agreement between different providers’ suspicion of infection and the correlation with patient outcomes using prospective data from a general medicine ward. Registered nurse (RN) suspicion of infection was collected every 12 hours and compared with medical doctor or advanced practice professional (MD/APP) suspicion, defined as an existing order for antibiotics or a new order for blood or urine cultures within the 12 hours before nursing screen time. During the study period, 1386 patients yielded 11,489 screens, 3744 (32.6%) of which met at least 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria. Infection was suspected by RN and MD/APP in 5.8% of cases, by RN only in 22.2%, by MD/APP only in 7.2%, and by neither provider in 64.7%. Overall agreement rate was 80.7% for suspicion of infection (κ = 0.11, P < 0.001). Progression to severe sepsis or shock was highest when both providers suspected infection in a SIRS-positive patient (17.7%), was substantially reduced with single-provider suspicion (6.0%), and was lowest when neither provider suspected infection (1.5%) (P < 0.001). Provider disagreement regarding suspected infection is common, with RNs suspecting infection more often, suggesting that a collaborative model for sepsis detection may improve timing and accuracy. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:256-258. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

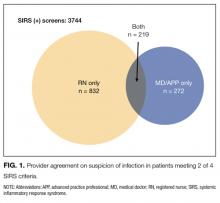

During the study period, 1386 distinct patients had 13,223 screening opportunities, with a 95.4% compliance rate. A total of 1127 screens were excluded for missing nursing documentation of suspicion of infection, leaving 1192 first screens and 11,489 total screens for analysis. Of the completed screens, 3744 (32.6%) met SIRS criteria; suspicion of infection was noted by both RN and MD/APP in 5.8% of cases, by RN only in 22.2%, by MD/APP only in 7.2%, and by neither provider in 64.7% (Figure 1). Overall agreement rate was 80.7% for suspicion of infection (κ = 0.11, P < 0.001). Demographics by subgroup are shown in the Supplemental Table. Progression to severe sepsis or shock was highest when both providers suspected infection in a SIRS-positive patient (17.7%), was substantially reduced with single-provider suspicion (6.0%), and was lowest when neither provider suspected infection (1.5%) (P < 0.001). A similar trend was found for in-hospital mortality (both providers, 6.3%; single provider, 2.7%; neither provider, 2.5%; P = 0.01). Compared with MD/APP-only suspicion, SIRS-positive patients in whom only RNs suspected infection had similar frequency of progression to severe sepsis or septic shock (6.5% vs 5.6%; P = 0.52) and higher mortality (5.0% vs 1.1%; P = 0.32), though these findings were not statistically significant.

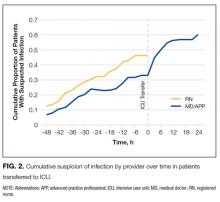

For the 121 patients (10.2%) transferred to ICU, RNs were more likely than MD/APPs to suspect infection at all time points (Figure 2). The difference was small (P = 0.29) 48 hours before transfer (RN, 12.5%; MD/APP, 5.6%) but became more pronounced (P = 0.06) by 3 hours before transfer (RN, 46.3%; MD/APP, 33.1%). Nursing assessments were not available after transfer, but 3 hours after transfer the proportion of patients who met MD/APP suspicion-of-infection criteria (44.6%) was similar (P = 0.90) to that of the RNs 3 hours before transfer (46.3%).

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal that bedside nurses and ordering providers routinely have discordant assessments regarding presence of infection. Specifically, when RNs are asked to screen patients on the wards, they are suspicious of infection more often than MD/APPs are, and they suspect infection earlier in ICU transfer patients. These findings have significant implications for patient care, compliance with the new national SEP-1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services quality measure, and identification of appropriate patients for enrollment in sepsis-related clinical trials.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore agreement between bedside RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection in sepsis screening and its association with patient outcomes. Studies on nurse and physician concordance in other domains have had mixed findings.9-11 The high discordance rate found in our study points to the highly subjective nature of suspicion of infection.

Our finding that RNs suspect infection earlier in patients transferred to ICU suggests nursing suspicion has value above and beyond current practice. A possible explanation for the higher rate of RN suspicion, and earlier RN suspicion, is that bedside nurses spend substantially more time with their patients and are more attuned to subtle changes that often occur before any objective signs of deterioration. This phenomenon is well documented and accounts for why rapid response calling criteria often include “nurse worry or concern.”12,13 Thus, nurse intuition may be an important signal for early identification of patients at high risk for sepsis.

That about one third of all screens met SIRS criteria and that almost two thirds of those screens were not thought by RN or MD/APP to be caused by infection add to the literature demonstrating the limited value of SIRS as a screening tool for sepsis.14 To address this issue, the 2016 sepsis definitions propose using the quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to identify patients at high risk for clinical deterioration; however, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign continues to encourage sepsis screening using the SIRS criteria.15

Limitations of this study include its lack of generalizability, as it was conducted with general medical patients at a single center. Second, we did not specifically ask the MD/APPs whether they suspected infection; instead, we relied on their ordering practices. Third, RN and MD/APP assessments were not independent, as RNs had access to MD/APP orders before making their own assessments, which could bias our results.

Discordance in provider suspicion of infection is common, with RNs documenting suspicion more often than MD/APPs, and earlier in patients transferred to ICU. Suspicion by either provider alone is associated with higher risk for sepsis progression and in-hospital mortality than is the case when neither provider suspects infection. Thus, a collaborative method that includes both RNs and MD/APPs may improve the accuracy and timing of sepsis detection on the wards.