Family report compared to clinician-documented diagnoses for psychiatric conditions among hospitalized children

BACKGROUND

Psychiatric comorbidity is common in pediatric medical and surgical hospitalizations and is associated with worse hospital outcomes. Integrating medical or surgical and psychiatric hospital care depends on accurate estimates of which hospitalized children have psychiatric comorbidity.

OBJECTIVE

We conducted a study to determine agreement of family report (FR) and clinician documentation (CD) identification of psychiatric diagnoses in hospitalized children.

DESIGN AND SETTING

This was a cross-sectional study at a tertiary-care children’s hospital.

PATIENTS

The patients were children and adolescents (age, 4-21 years) who were hospitalized for medical or surgical indications.

MEASUREMENTS

Psychiatric diagnoses were identified from structured interviews (FR) and from inpatient notes and International Classification of Diseases codes in medical records (CD). We compared estimates of point prevalence of any comorbid psychiatric diagnosis using each method, and estimated FR–CD agreement in identifying psychiatric comorbidity in hospitalized children.

RESULTS

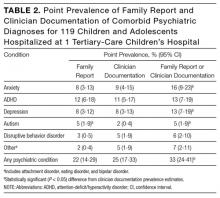

Of 119 study patients, 26 (22%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 14%-29%) had a psychiatric comorbidity identified by FR, 30 (25%; 95% CI, 17%-34%) had it identified by CD, and 37 (23%-40%) had it identified by FR or CD. Agreement between FR and CD was low overall (κ = .46; 95% CI, .27-.66), highest for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (κ = .78; 95% CI, .59-.97), and lowest for anxiety disorders (κ = .11; 95% CI, –.16 to .56).

CONCLUSIONS

Current methods may underestimate the prevalence of psychiatric conditions in hospitalized children. Information from multiple sources may be needed to develop accurate estimates of the scope of the population in need of services so that mental health resources can be appropriately allocated. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Patients eligible for inclusion in the study were 4 to 21 years old and hospitalized for a medical or surgical indication. Patients were ineligible if they were hospitalized for a primary psychiatric indication, were medically unstable (eg, received end-of-life care or escalating interventions for a life-threatening condition), had significant cognitive impairment precluding communication (eg, history of severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy), or did not speak English (pertains to consenting parent, guardian, or patient).

The cross-sectional patient sample was selected using a point prevalence recruitment strategy. All eligible patients on each of CHOP’s 20 inpatient medical, surgical, and critical care units were approached for study participation on 2 dates between July 2015 and March 2016. To avoid enrolling the same patient multiple times for a single hospitalization, we separated recruitment dates on each unit by at least 3 months. A goal sample size of 100 to 150 patients was selected to provide precision sufficient to achieve a confidence interval (CI) of 10% around an estimate of the point prevalence of any mental health condition.

To obtain family report of prior psychiatric diagnoses, we interviewed patients and/or their parents during the hospitalization. For 18- to 21-year-old patients, the adolescent patient completed the interview. For patients under 18 years old, parents completed the interview, and for 14- to 17-year-old adolescents,either the parent, the patient, or both could complete the interview. Adolescents were asked to complete the interview confidentially without a parent present. The structured interview included questions derived from the National Survey of Children’s Health24 and the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents22 to report the patient’s active psychiatric conditions. Interviewees reported whether the patient had ever been diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder, whether the condition was ongoing in the year prior to hospitalization, and whether the patient received any mental health services in clinical settings or school in the 12 months prior to hospitalization.

For CD, we identified a psychiatric diagnosis associated with the index hospitalization if a psychiatric diagnosis was noted in the patient’s admission note, discharge summary, or hospital problem list, or if an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code for a psychiatric diagnosis was submitted for billing for the index hospitalization. The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project condition classification system was used to sort psychiatric condition codes25-27 into 5 categories: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, depression, disruptive behavior disorders, and autism spectrum disorders. A residual category of other, less common psychiatric conditions included eating disorders, attachment disorders, and bipolar disorder.

For each condition category, we determined the point prevalence of having a psychiatric diagnosis identified by FR and having a diagnosis identified by CD. We used McNemar tests to compare point prevalence estimates, the Clopper-Pearson method to calculate CIs around the estimates,28 and Cohen κ statistics to estimate FR–CD agreement regarding psychiatric diagnoses, grouping patients by type of psychiatric diagnosis and by clinical and demographic characteristics. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < 0.05 was used for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata Version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

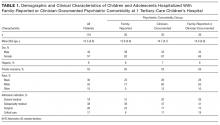

Of 640 patients hospitalized on study recruitment dates, 411 were ineligible for the study (282 were <4 or >21 years old, 42 were not English speakers, 37 had cognitive impairment, 30 were not medically stable, and 20 were admitted for a primary psychiatric diagnosis). Of the 229 eligible patients, 119 (52%) enrolled. Included patients were 57% female; 9% Hispanic; and 35% black, 55% white, and 15% other race. Forty-eight percent of the enrollees had Medicaid (48%), and 52% had private health insurance. Mean age was 12.3 years. Of enrolled patients, 38% were admitted to subspecialty medical services. Enrollee demographics were representative of hospital-level demographics for the study-eligible population; there were no significant differences in age, sex, race, ethnicity, payer type, or hospital service admission type between enrollees and patients who declined to participate (all Ps > 0.05). Table 1 lists demographic and clinical characteristics of the complete study sample and of the groups with FR- or CD-identified psychiatric diagnosis.

Of 119 enrollees, 26 (22%; 95% CI, 15%-30%) had at least 1 FR-identified comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, and 30 (25%; 95% CI, 17%-33%) had at least 1 CD-identified diagnosis. In 13 cases, adolescents (age, 14-17 years) and their parents both completed the structured interview; there were no discrepancies between interview results.

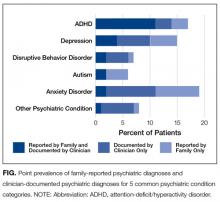

In total, 39 of 119 patients (33%, 95% CI: 24-42%) had either a family-reported or clinician-documented psychiatric diagnosis at the time of hospitalization. For 17 of 119 patients (14%; 95% CI: 9-22%), family-report and clinician-documentation both identified the patient as having a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. For 9 of 119 patients (8%; 95% CI: 4-14%) families reported a psychiatric diagnosis, but clinicians did not document one. Conversely, for another 13 of 119 patients (11%; 95% CI: 6-18%), a clinician documented a psychiatric diagnosis but the family did not report one. The Figure shows the point prevalence of family-reported psychiatric diagnoses and clinician-documented psychiatric diagnoses for 5 common psychiatric condition categories.

The most common psychiatric conditions reported by families or documented by clinicians were ADHD (n=16, 13%),

Although point prevalence estimates were similar for FR- and CD-identified comorbid psychiatric conditions, FR–CD agreement was modest. It was fair for any psychiatric diagnosis (κ = .49; 95% CI, .30-.67), highest for ADHD (κ = .79; 95% CI, .61-.96), and fair or poor for other psychiatric conditions (κ range, .11-.48). Table 3 lists the FR–CD agreement data for psychiatric diagnoses for hospitalized children and adolescents.

We compared the distribution of FR and CD psychiatric diagnoses with FR use of mental health services. Of the 119 patients, 47 (39%; 95% CI, 31%-49%) had used mental health services within the year before hospitalization. Of these 47 patients, 15 (32%; 95% CI, 19%-47%) had a psychiatric diagnosis identified by both FR and CD, 6 (13%; 95% CI, 5%-26%) had a diagnosis identified only by FR, 8 (17%; 95% CI, 8%-30%) had a diagnosis identified only by CD, and 18 (38%; 95% CI, 25%-54%) had no FR- or CD-identified diagnosis. For 5 (38%; 95% CI, 14%-68%) of the 13 patients with a CD-only diagnosis, the family reported no use of mental health services within the year before hospitalization.