Screening for depression in hospitalized medical patients

Depression among hospitalized patients is often unrecognized, undiagnosed, and therefore untreated. Little is known about the feasibility of screening for depression during hospitalization, or whether depression is associated with poorer outcomes, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates. We searched PubMed and PsycINFO for published, peer-reviewed articles in English (1990-2016) using search terms designed to capture studies that tested the performance of depression screening tools in inpatient settings and studies that examined associations between depression detected during hospitalization and clinical or utilization outcomes. Two investigators reviewed each full-text article and extracted data. The prevalence of depression ranged from 5% to 60%, with a median of 33%, among hospitalized patients. Several screening tools identified showed high sensitivity and specificity, even when self-administered by patients or when abbreviated versions were administered by individuals without formal training. With regard to outcomes, studies from several individual hospitals found depression to be associated with poorer functional outcomes, worse physical health, and returns to the hospital after discharge. These findings suggest that depression screening may be feasible in the inpatient setting, and that more research is warranted to determine whether screening for and treating depression during hospitalization can improve patient outcomes. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:118-125. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Study Selection

Articles were eligible if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals, included at least 20 adults hospitalized for nonpsychiatric reasons, and described the use of at least 1 measure of depression. The studies must have either tested the validity of a depression screening tool or examined the association between depression screening and clinical or utilization outcomes. Two investigators reviewed each title, abstract, and full-text article to determine eligibility, then reached a consensus on which studies to include in this review.

Data Extraction

Two investigators reviewed each full-text article to extract information related to study design, population, and outcomes regarding screening tool analysis or clinical results. From articles that assessed the performance of depression screening tools, we extracted information related to the nature and application of the index test, the nature and application of the reference test, the prevalence of depression, and the sensitivity and specificity of the index test compared with the reference test. For articles that focused on the association between depression screening and clinical or utilization outcomes, the data on relevant clinical outcomes included symptom severity, quality of life, and daily functioning, whereas the data on utilization outcomes included length of stay, readmission, and the cost of care.

RESULTS

Altogether, the search identified 3226 records. After eliminating duplicates and abstracts not suitable for inclusion (Figure), 101 articles underwent full-text review and 32 were found to be eligible. Of these, 12 focused on the association between depression and clinical or utilization outcomes, while 20 assessed the performance of depression screening tools.

Depression Screening Tools

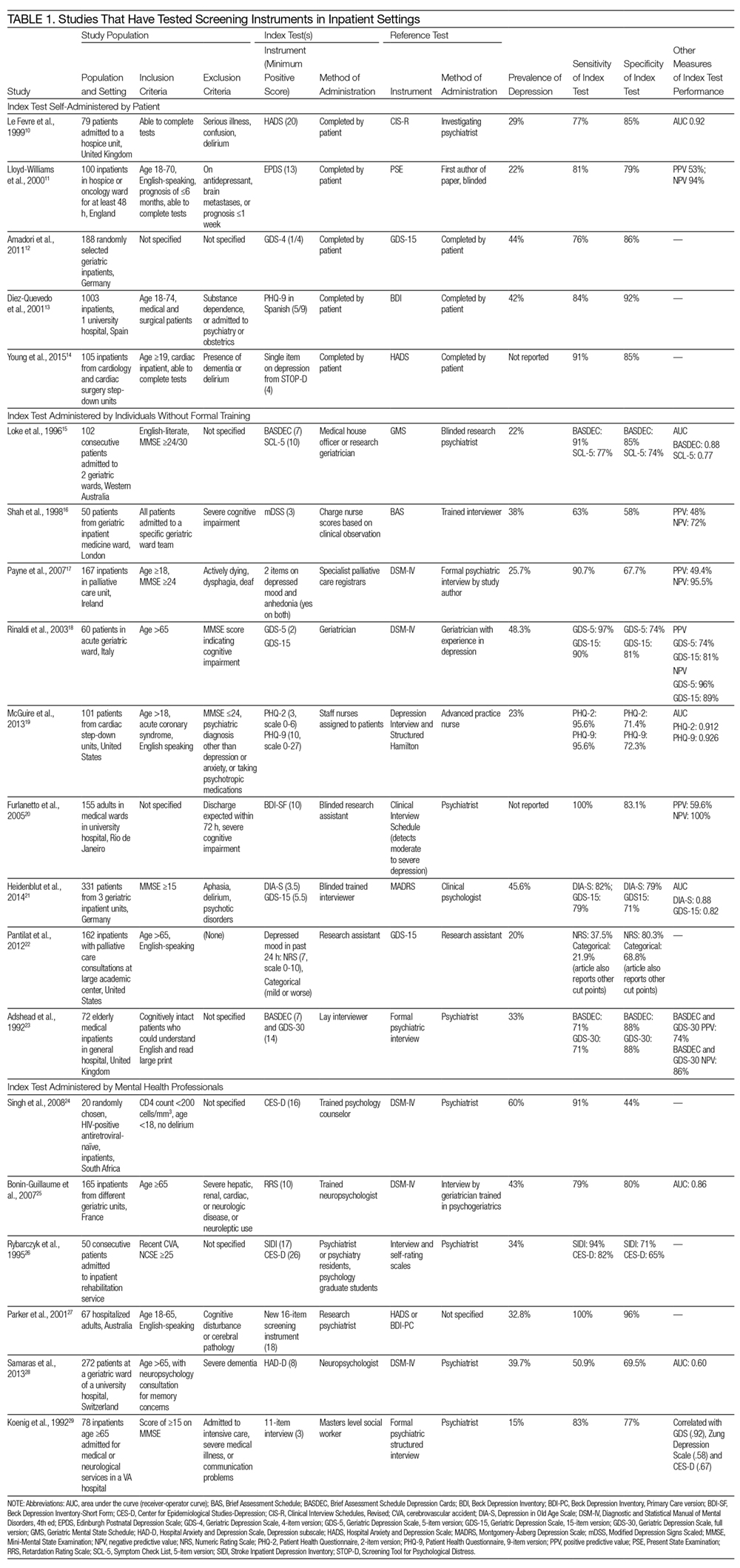

Table 1 describes the index and reference instruments as well as methods of administration, the prevalence of depression, and the sensitivity and specificity of the index instruments relative to the reference instruments. Across the 20 studies, the prevalence of depression ranged from 15% to 60%, with a median of 34%.10–29 This finding may reflect different methods of screening or variation among diverse hospitalized populations. Many of the studies excluded patients with cognitive impairment or communication barriers.

The included studies tested a wide range of unique instruments, and compared them with diverse reference standards. Five studies examined instruments that were self-administered by patients10–14; 9 studies assessed instruments administered by nurses, physicians, or research staff members without formal psychiatric training15–23; and 6 studies evaluated instruments administered by mental health professionals.24–29 Four studies compared different instruments that were administered in the same manner (eg, both self-administered by patients).12–14,22 In the remaining studies, both instruments and methods of administration differed between the index and reference conditions.

Eight studies tested brief instruments with 5 or fewer items, most of which exhibited good sensitivity (range 38%–91%) and specificity (range 68%–86%) relative to longer instruments.12,14–19,22 In 2 of these studies, instruments were self-administered. In 1 case, a single self-administered item from the STOP-D instrument (“Over the past 2 weeks, how much have you been bothered by feeling sad, down, or uninterested in life?”) performed nearly as well as the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.14 In the other 6 studies testing brief instruments, the instruments were administered by individuals without formal training.15–19,22 In 1 such study, geriatricians asking 2 questions about depressed mood and anhedonia performed well compared with a formal psychiatric interview.17

Four studies tested variations of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).12,18,21,23 In 3 of these studies, abbreviated versions of the GDS exhibited relatively high sensitivity and specificity.12,18,21 However, a study comparing the 15-item GDS (GDS-15) with the GDS-4 found that GDS-15 correctly classified 10% more patients with suspected depression.12 Two studies examined variations of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). One study found that both the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 obtained by staff nurses performed well relative to a comprehensive assessment by a trained advanced practice nurse.13,19

When reported, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and area under the receiver-operator curve were generally high.

Depression and Clinical or Utilization Outcomes

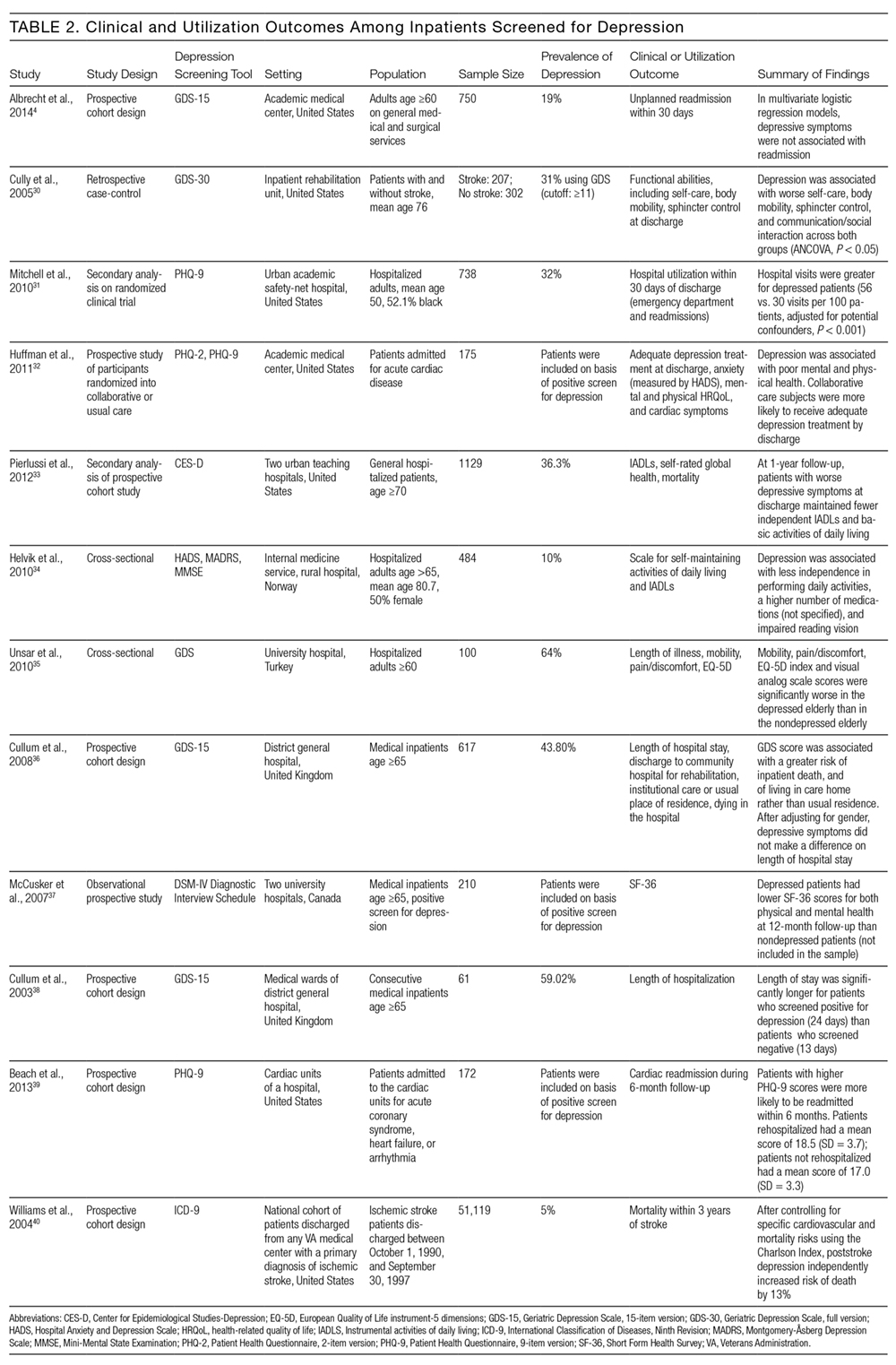

Of the 12 studies that reported either clinical or utilization outcomes for depression screening in an inpatient setting,4,30–40 3 measured rates of rehospitalization.4,31,39 The other 9 studies tested for associations between symptoms of depression and either health or treatment outcomes. Table 2 provides a more detailed description of the study designs and results.

Other studies found that depression was associated with reduced functional abilities such as mobility and self-care,30,32–34 and increased hospital readmission31 as well as physical and mental health deficits.37 Interestingly, although 1 study did not find that depression and hospital readmission were closely linked (frequency at 19%), it found that comorbid illness and previous hospitalizations predicted readmission.4

We also evaluated the associations between depression diagnosed in the inpatient studies and 2 types of outcomes. The first type includes clinical outcomes including symptom severity, quality of life, and daily functioning. Most studies we identified assessed clinical outcomes, and all detected an association between depression and worse clinical outcomes. The second type includes healthcare utilization, which can be measured with the patients’ length of hospital stay, readmission and cost of care. In 1 such study, Mitchell aet al.31 reported a 54% increase in readmission within 30 days of discharge among patients who screened positive for depression.31 Additionally, Cully et al.30 found that depression may impinge on the recovery process of acute rehabilitation patients.