Impact of patient-centered discharge tools: A systematic review

Patient-centered discharge tools provide an opportunity to engage patients, enhance patient understanding, and improve capacity for self-care and postdischarge outcomes.

Purpose

To review studies that engaged patients in the design or delivery of discharge instruction tools and that tested their effect among hospitalized patients.

Data Sources

We conducted a search of 12 databases and journals from January 1994 through May 2014, and references of retrieved studies.

Study Selection

English-language studies that tested discharge tools meant to engage patients were selected. Studies that measured outcomes after 3 months or without a control group or period were excluded.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers assessed the full-text papers and extracted data on features of patient engagement.

Data Synthesis

Thirty articles met inclusion criteria, 28 of which examined educational tools. Of these, 13 articles involved patients in content creation or tool delivery, with only 6 studies involving patients in both. While many of these studies (10 studies) demonstrated an improvement in patient comprehension, few studies found improvement in patient adherence despite their engagement. A few studies demonstrated an improvement in self-efficacy (2 studies) and a reduction in unplanned visits (3 studies).

Conclusions

Improving patient engagement through the use of media, visual aids, or by involving patients when creating or delivering a discharge tool improves comprehension. However, further studies are needed to clarify the effect on patient experience, adherence, and healthcare utilization postdischarge. Better characterization of the level of patient engagement when designing discharge tools is needed given the heterogeneity found in current studies. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:110-117. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement was followed as a guideline for reporting throughout this review.11

Data Sources

A literature search was undertaken using the following databases from January 1994 or their inception date to May 2014: Medline, Embase, SIGLE, HTA, Bioethics, ASSIA, Psych Lit, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EconLit, ERIC, and BioMed Central. We also searched relevant design-focused journals such as Design Issues, Journal of Design Research, Information Design Journal, Innovation, Design Studies, and International Journal of Design, as well as reference lists from studies obtained by electronic searching. The following key words and combination of key words were used with the assistance of a medical librarian: patient discharge, patient-centered discharge, patient-centered design, design thinking, user based design, patient education, discharge summary, education. Additional search terms were added when identified from relevant articles (Appendix).

Inclusion Criteria

We included all English-language studies with patients admitted to the hospital irrespective of age, sex, or medical condition, which included a control group or time period and which measured patient outcomes within 3 months of discharge. The 3-month period after discharge is often cited as a time when outcomes could reasonably be associated with an intervention at discharge.2

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not have clear implementation of a patient-centered tool, a control group, or those whose tool was used in the emergency department or as an outpatient were excluded. Studies that included postdischarge tools such as home visits or telephone calls were excluded unless independent effects of the predischarge interventions were measured. Studies with outcomes reported after 3 months were excluded unless outcomes before 3 months were also clearly noted.

All searches were entered into Endnote and duplicates were removed. A 2-stage inclusion process was used. Titles and abstracts of articles were first screened for meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria by 1 reviewer. A second reviewer independently checked a 10% random sample of all the abstracts that met the initial screening criteria. If the agreement to exclude studies was less than 95%, criteria were reviewed before checking the rest of the 90% sample. In the second stage, 2 independent reviewers examined paper copies of the full articles selected in the first stage. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion or a third reviewer if no agreement could be reached.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The following information was extracted from the full reference: type of study, population studied, control group or time period, tool used, and outcomes measured. Based on the National Health Care Quality report’s priorities and goals on patient and/or family engagement during transitions of care, educational tools were further described based on method of teaching, involvement of the care team, involvement of the patient in the design or delivery of the tool, and/or the use of visual aids.12 All primary outcomes were classified according to 3 categories: improved knowledge/comprehension, patient experience (patient satisfaction, self-management/efficacy such as functional status, both physical and mental), and health outcomes (unscheduled visits or readmissions, adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up, and mortality).

No quantitative pooling of results or meta-analysis was done given the variability and heterogeneity of studies reviewed. However, following guidelines for Effect Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Risk of Bias criteria,13 studies that had a higher risk of bias such as uncontrolled before-after studies or studies with only 1 intervention or control site (historical controls, eg) were excluded from the final review because of the difficulties in attributing causation. Only primary outcomes were reported in order to minimize type II errors.

RESULTS

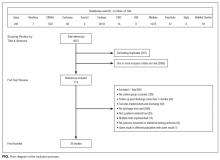

Our search revealed a total of 3699 studies after duplicates had been removed (Figure). A total of 714 references were included after initial review by title and abstract and 30 studies after full-text review. Agreement on a 10% random sample of all abstracts and full text was 79% (k=0.58) and 86% (k=0.72), respectively. Discussion was needed for fewer than 100 references, and agreement was subsequently reached for 100%.

There were 22 randomized controlled trials and 8 nonrandomized studies (5 nonrandomized controlled trials and 3 controlled before-after studies). Most of these studies were conducted in the United States (13/30 studies), followed by other European countries (5 studies), and the United Kingdom (4 studies). A large number of studies were conducted among patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors (10 studies), followed by postsurgical patients such as coronary artery bypass graft surgery or orthopaedic surgery (5 studies). Five of 30 studies were conducted among individuals older than 65 years. Most studies excluded patients who did not speak English or the country’s official language; only 3 studies included patients with limited literacy, patients who spoke other languages, or caregivers if the patients could not communicate.

Most studies tested the impact of educational discharge interventions (28 of 30 studies) (Table 1). Quite often, it was a member of the research team who carried out the patient education. Only 3 studies involved multiple members of the care team in designing or reviewing the discharge tool with the patient. Almost half (12 studies) targeted multiple aspects of postdischarge care, including medications and side effects, signs and symptoms to consider, plans for follow-up, dietary restrictions, and/or exercise modifications. Many (19 studies) provided education using one-on-one teaching in association with a discharge tool, accompanied by a written handout (13 studies), audiotape (2 studies), or video (3 studies). While 13 studies had patients involved in creating what content was discussed and 14 studies had patients involved in the delivery of the tool, only 6 studies had patients involved in both design and delivery of the tool. Nine studies also used visual aids such as pictures, larger font, or use of a tool enhanced for patients with language barriers or limited health literacy.

Among all 30 studies included, 16 studies tested the impact of their tool on comprehension postdischarge, with 10 studies demonstrating an improvement among patients who had received the tool (Table 2). Five studies evaluated healthcare utilization outcomes such as readmission, length of stay, or physician visits after discharge and 2 studies found improvements. Twelve studies also studied the impact on adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up instructions postdischarge. However, only 4 of these 12 studies showed a positive impact. Only 2 studies tested the impact on a patient’s ability to self-manage once at home, and both studies reported positive statistical outcomes. Few studies measured patient experience (such as patient satisfaction or improvement in self-efficacy) or mortality postdischarge.