Poison ivy: How effective are available treatments?

In this study, only one treatment approach significantly reduced pruritus. Three approaches were often associated with recurrences of rash or symptoms.

No statistically significant associations were found between the baseline non-treatment variables and duration of symptoms and signs. Patient-initiated treatments were also not associated with duration of symptoms and signs following the initial clinician visit.

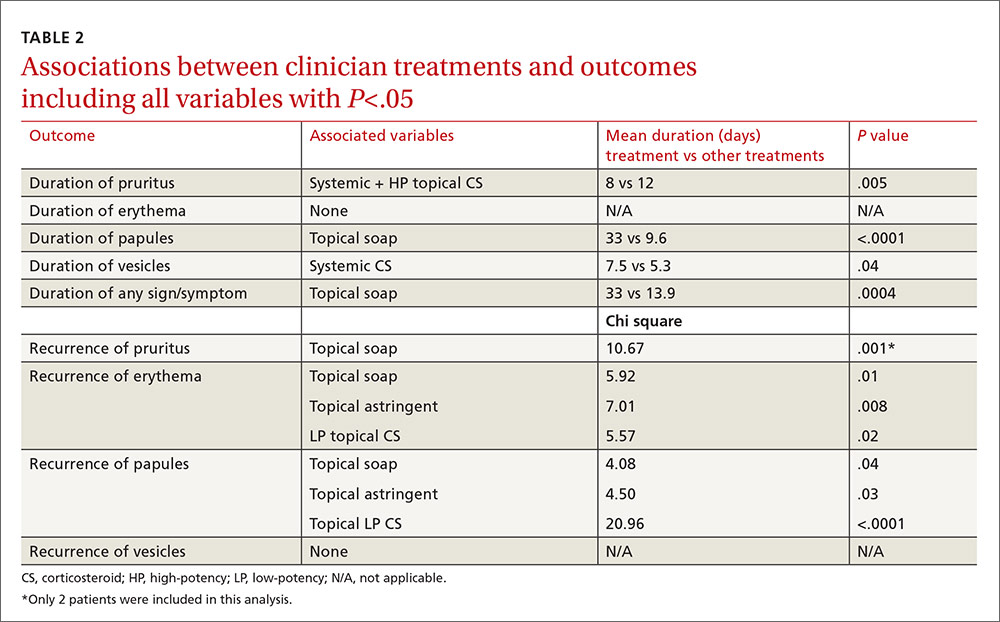

Of the treatments prescribed by clinicians or independently chosen by patients following their initial office visit, only systemic corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids were associated with a significantly shorter duration of itching (P=.005). No treatment was associated with reduced duration of erythema, papules, or vesicles. Use of topical soaps was associated with a longer duration of papules (P<.0001) and of total duration of signs or symptoms (P=.0004) compared with other treatments.

Location and characteristics of the rash were not associated with likelihood of recurrence following treatment. Post-visit use of a topical soap was associated with recurrence of itching (P=.001) and erythema (P=.01). Recurrence of erythema was also more frequent in patients prescribed topical astringents (beta coefficient=0.28; P=.008), and recurrence of papules was more common in patients treated with low-potency topical corticosteroids (P<.0001). These results and several others that almost reached statistical significance are shown in TABLE 2.

In the multivariable models, the only variable associated with duration of pruritus was the combination of systemic and high-potency topical corticosteroids (8 vs 12 days.) Use of only parenteral or only high-potency topical corticosteroids did not predict shorter duration of pruritus. Use of topical soaps was associated with longer duration of papules (33 vs 9.6 days) and longer duration of any symptoms (33 vs 13.9 days). It was also associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence of pruritus (chi square test [χ2], 10.67) and recurrence of erythema (χ2, 5.92) after initial resolution. Topical astringent use was predictive of recurrence of erythema (χ2, 7.01) and use of low-potency corticosteroids was associated with recurrence of papules (χ2, 20.96).

DISCUSSION

While network clinicians felt that studying poison ivy was of interest and importance, and we had preliminary survey information to suggest it was a common problem treated in primary care, our data suggest that clinical encounters for poison ivy are actually quite uncommon (less than 0.4% of all encounters) even during peak months. Our problems with recruitment were therefore unexpected, and we ended up with far fewer enrolled patients than we had projected, and needed, based on our power analysis. Also based on our preliminary survey, we anticipated considerably more variation in treatment approach than we found. Most clinicians recommended either an oral, parenteral, or high-potency topical corticosteroid, and some also recommended an oral antihistamine, usually diphenhydramine.

The literature and common sense suggest that most patients who seek medical treatment for poison ivy are primarily concerned about itching. Even with the smaller-than-anticipated number of participants in this study, we were able to show that the combination of a systemic (oral or parenteral) corticosteroid and a high-potency topical corticosteroid was associated with a statistically significant shorter duration of pruritus with no recurrence following treatment. We found no evidence that systemic corticosteroids alone, parenteral corticosteroids alone, or high-potency topical corticosteroids alone had any effect on duration of signs or symptoms, even at an alpha of .05. We also found no evidence that oral antihistamines were associated with a shorter duration of pruritus (P=.06); with a larger sample size, we might have found a difference.