Management of Metastatic Gastric Cancer

Persistent epigastric abdominal pain and weight loss are the most common early symptoms of gastric cancer. Nausea, early satiety, dysphagia, and occult GI bleeding can be other presenting signs. Patients presenting with alarm symptoms of nausea, emesis, early satiety, abdominal pain, or weight loss should be fully evaluated with upper GI endoscopy. Early diagnosis of gastric cancer is essential in obtaining a curative resection. However, at least 40% of patients present with de novo metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis.12 Gastric cancer spreads by direct extension through the gastric wall, with the liver, peritoneum, and regional lymph nodes being the most common sites of metastatic deposits.13 Classically, Virchow’s node, the left supraclavicular lymph node, is involved with metastatic gastric cancer. Involvement of the left axillary lymph node (Irish node) or a periumbilical nodule (Sister Mary Joseph node) may also be observed. Other, less commonly noted sites of metastatic disease include the ovaries, central nervous system, bone, lung, and soft tissues.13

Upper GI endoscopy is the best method for determining tumor location and extent and obtaining a specimen for a definitive tissue diagnosis.14 It is essential to accurately identify the location of the tumor in the stomach and relative to the GEJ. The American Joint Committee on Cancer classification defines tumors involving the GEJ with an epicenter no more than 2 cm into the proximal stomach as esophageal cancers.15 Tumors of the GEJ with their epicenter more than 2 cm into the proximal stomach are defined as gastric cancers. If metastatic disease is suspected, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast can be obtained to determine the extent of disease spread. In the absence of any metastatic disease, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be conducted to determine the depth of tumor invasion (T staging) and lymph node status. In the era of targeted therapy, patients with metastatic disease should undergo testing for human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER-2) expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. Patients should be staged according to the TNM staging system.

FIRST-LINE TREATMENT OPTIONS

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) and is found to have a gastric cardia mass extending into the distal esophagus. EUS also demonstrates multiple abdominal and mediastinal lymph nodes. No gastric outlet obstruction is found. Biopsy shows poorly differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma. Warthin–Starry stain is negative for H. pylori organism. The tumor cells are positive for cytokeratin (CK7), CK19, and mucin-1 gene (MUC1); focally positive for CK20; and negative for MUC2. HER2 testing results are reported as immunohistochemistry (IHC) 3+, consistent with strongly positive HER2 protein expression. Further IHC testing for mismatch repair (MMR) proteins shows intact nuclear expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 protein, consistent with a low probability of MSI-high tumor. The tumor is found to be PD-L1 positive. Imaging reveals abnormal mass-like nodular thickening of the gastric wall, with an infiltrative opacity within the pancreatico-duodenal groove, suspicious for tumor infiltration. Multiple metastatic deposits are noted in the liver, peritoneum, and bilateral lungs. There is extensive gastrohepatic ligament and periportal lymphadenopathy and mild enlargement of the pulmonary hilar lymph nodes. These findings are consistent with stage 4 (T4bN3aM1) gastric cancer. Given these findings, staging laparoscopy is deferred.

• What are the first-line treatment options for patients with metastatic gastric cancer?

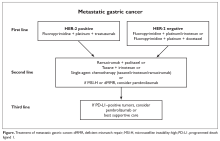

Patients with metastatic gastric cancer have a poor prognosis, and management is stratified based on performance status (Figure). In patients with good performance status, systemic chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. The goal of therapy is not curative, but rather treatment focuses on palliation of symptoms arising from tumor spread. Given this treatment goal, there has been considerable interest in clarifying the utility of chemotherapy as opposed to best supportive care. In a recent Cochrane review of 64 randomized control trials involving 11,698 patients, chemotherapy was found to improve OS by 6.7 months as compared to best supportive care (hazard ratio [HR] 0.3 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.24 to 0.55]).16 Five classes of cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents have demonstrated activity in gastric cancer. These include fluoropyrimidine (either infusional fluorouracil or capecitabine), platinum agents (cisplatin or oxaliplatin), taxanes (docetaxel or paclitaxel), anthracyclines (epirubicin), and irinotecan.13 Treatment options are further divided based on whether the patient has HER2-overexpressing or non-expressing malignancy.