Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Update on Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Treatment

Neoadjuvant Therapy

Case Continued

The patient is referred to oncology. Blood work reveals a CA 19-9 level of 100 U/mL (reference range < 35 U/mL) and a staging CT scan of the chest reveals a benign-appearing 3-mm nodule (no prior imaging for comparison). CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis does not define venous vasculature involvement appropriately and hence MRI of the abdomen and pelvis is performed. MRI reveals a pancreatic head mass measuring 3.0 × 2.7 cm, without arterial or venous vasculature invasion. However, the mass is abutting the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein and there is a new nonspecific 8-mm aortocaval lymph node.

- What are the current approaches to treating patients with resectable, unresectable, and metastatic disease?

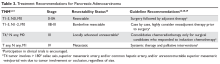

Accurate staging and assessment of surgical resectability in pancreatic cancer are paramount as these steps prevent a futile morbid Whipple procedure in patients with advanced disease and a high risk of recurrence. Conversely, it allows patients with low-volume disease to undergo a potentially curative surgery. Approximately 20% of patients present with resectable disease, 40% present with locally advanced unresectable tumors (eg, involvement of critical vascular structures), and 40% present with metastatic disease.3 Treatment for resectable pancreatic cancer continues to be upfront surgery, although neoadjuvant therapy with either chemoradiation, radiation alone, or chemotherapy is an option per guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO),28 the NCCN,26 and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO),29 particularly for patients with borderline resectable tumors (Table 3).

Systemic chemotherapy is recommended for fit candidates with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic disease, with an emphasis on supportive palliative measures. Palliative interventions include biliary stenting, duodenal stent for relieving gastric-outlet obstruction, and celiac axis nerve blocks, when indicated. Routine preoperative biliary stent placement/drainage in patients undergoing subsequent surgery for pancreatic cancer located in the head is associated with an increased risk of surgical complications when compared with up-front surgery without prior biliary drainage, and thus stent placement/drainage is not recommended.26 Aggressive supportive management of symptoms, such as cancer-associated pain, anorexia-cachexia syndromes, and anxiety-depression disorders, should remain a primary palliative focus.

Case Continued

A multidisciplinary tumor board discusses the patient’s case and deems the cancer borderline resectable; neoadjuvant therapy is recommended. The patient is started on treatment with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel as first-line neoadjuvant therapy. After 4 cycles, the CA 19-9 level drops to 14 U/mL, and MRI reveals a smaller head mass of 1.3 × 1.4 cm with stable effacement of the superior mesenteric vein and no portal vein involvement; the aortocaval lymph node remains stable. At tumor board, it is evident that the patient has responded to therapy and the recommendation is to treat with gemcitabine chemoradiotherapy before surgery.

- What neoadjuvant therapy strategies are used in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma?

There are no established evidence-based recommendations for neoadjuvant therapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer or patients with unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. However, there are ongoing trials to investigate this treatment approach, and it is offered off-label in specific clinical scenarios, such as in the case patient described here. In patients with borderline resectable disease, preoperative chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation is a routine practice in most cancer centers,32 and ongoing clinical trials are an option for this cohort of patients (eg, Southwest Oncology Group Trial 1505, NCT02562716). The definitions of borderline resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer have been described by the NCCN,26 although most surgeons consider involvement of the major upper abdominal blood vessels the main unresectability criterion; oncologists also consider other parameters such as suspicious lesions on scans, worsening performance status, and a significantly elevated CA 19-9 level suggestive of disseminated disease.28 The goal of a conversion approach by chemotherapy with or without radiation for borderline and unresectable cancers is to deliver a tolerable regimen leading to tumor downstaging, allowing for surgical resection. No randomized clinical trial has shown a survival advantage of this approach. Enrollment in clinical trials is preferred for patients with borderline and unresectable cancer, and there are trials that are currently enrolling patients.

The main treatment strategies for patients with locally advanced borderline and unresectable pancreatic cancer outside of a clinical trial are primary radiotherapy, systemic chemotherapy, and chemoradiation therapy. Guidelines from ASCO, NCCN, and ESMO recommend induction chemotherapy followed by restaging and consolidation chemoradiotherapy in the absence of progression.26,28,29 There is no standard chemoradiation regimen and the role of chemotherapy sensitizers, including fluorouracil, gemcitabine, and capecitabine (an oral fluoropyrimidine substitute), and targeted agents in combination with different radiation modalities is now being investigated.

Fluorouracil is a radio-sensitizer that has been used in locally advanced pancreatic cancer based on experience in other gastrointestinal malignancies; data shows conflicting results with this drug. Capecitabine and tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1) are oral prodrugs that can safely replace infusional fluorouracil. Gemcitabine, a more potent radiation sensitizer, is very toxic, even at low-doses twice weekly, and does not provide a survival benefit, as demonstrated in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 89805 trial, a phase 2 study of patients with surgically staged locally advanced pancreatic cancer.33 Gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy was also evaluated in the Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) E4201 trial, which randomly assigned patients to receive gemcitabine alone (at 1000 mg/m2/wk for weeks 1 through 6, followed by 1 week rest, then weekly for 3 out of 4 weeks) or gemcitabine (600 mg/m2/wk for weeks 1 to 5, then 4 weeks later 1000 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks) plus radiotherapy (starting on day 1, 1.8 Gy/fraction for total of 50.4 Gy).34 Patients with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer had a better OS outcome with gemcitabine in combination with radiation therapy (11.1 months) as compared with patients who received gemcitabine alone (9.2 months). Although there was a greater incidence of grade 4 and 5 treatment-related toxicities in the combination arm, no statistical differences in quality-of-life measurements were reported. Gemcitabine-based and capecitabine-based chemoradiotherapy were compared in the open-label phase 2 multicenter randomized SCALOP trial.35 Patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer were assigned to receive 3 cycles of induction with gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 days 1, 8, and 15 and capecitabine 830 mg/m2 days 1 to 21 every 28 days; patients who had stable or responding disease were randomly assigned to receive a fourth cycle followed by capecitabine (830 mg/m2 twice daily on weekdays only) or gemcitabine (300 mg/m2 weekly) with radiation (50.4 Gy over 28 fractions). Patients treated with capecitabine-based chemoradiotherapy had higher nonsignificant median OS (17.6 months) and median progression-free survival (12 months) compared to those treated with gemcitabine (14.6 months and 10.4 months, respectively).