Malignant olecranon bursitis in the setting of multiple myeloma relapse

Accepted for publication June 14, 2018

Correspondence

Maxwell M Krem, MD, PhD; maxwell.krem@louisville.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(4):e202-e205

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0393

Submit a paper here

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

,Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

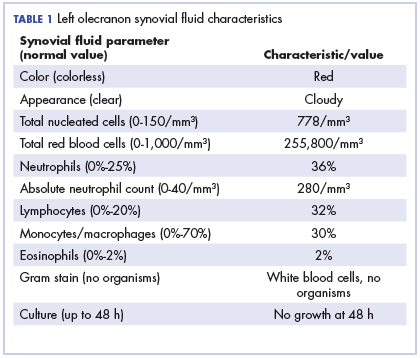

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

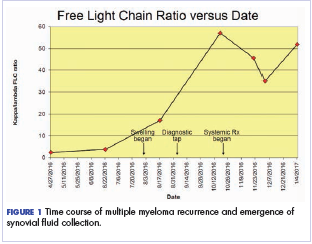

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

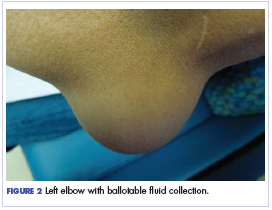

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

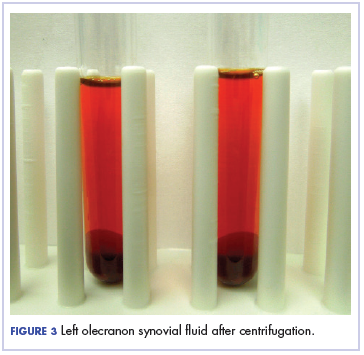

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.