Tumor heterogeneity: a central foe in the war on cancer

Citation JCSO 2018;16(3):e167-e174

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi: ttps://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0407

Submit a paper here

A major challenge to effective cancer treatment is the astounding level of heterogeneity that tumors display on many different fronts. Here, we discuss how a deeper appreciation of this heterogeneity and its impact is driving research efforts to better understand and tackle it and a radical rethink of treatment paradigms.

A complex and dynamic disease

The nonuniformity of cancer has long been appreciated, reflected most visibly in the variation of response to the same treatment across patients with the same type of tumor (inter-tumor heterogeneity). The extent of tumor heterogeneity is being fully realized only now, with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies. Even within the same tumor, there can be significant heterogeneity from cell to cell (intra-tumor heterogeneity), yielding substantial complexity in cancer.

Heterogeneity reveals itself on many different levels. Histologically speaking, tumors are composed of a nonhomogenous mass of cells that vary in type and number. In terms of their molecular make-up, there is substantial variation in the types of molecular alterations observed, all the way down to the single cell level. In even more abstract terms, beyond the cancer itself, the microenvironment in which it resides can be highly heterogeneous, composed of a plethora of different supportive and tumor-infiltrating normal cells.

,Heterogeneity can manifest spatially, reflecting differences in the composition of the primary tumor and tumors at secondary sites or across regions of the same tumor mass and temporally, at different time points across a tumor’s natural history. Evocative of the second law of thermodynamics, cancers generally become more diverse and complex over time.1-3

A tale of 2 models

It is widely accepted that the transformation of a normal cell into a malignant one occurs with the acquisition of certain “hallmark” abilities, but there are myriad ways in which these can be attained.

The clonal evolution model

As cells divide, they randomly acquire mutations as a result of DNA damage. The clonal evolution model posits that cancer develops as the result of a multistep accumulation of a series of “driver” mutations that confer a promalignant advantage to the cell and ultimately fuel a cancerous hallmark.

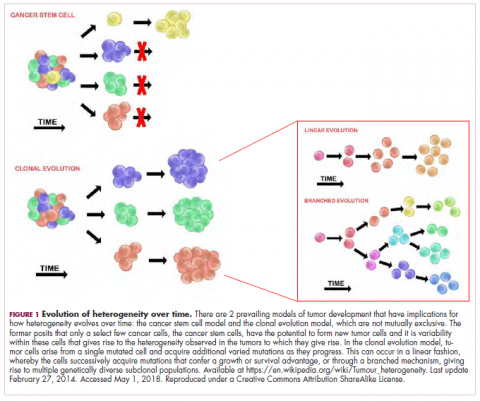

This evolution can occur in a linear fashion, whereby the emergence of a new driver mutation conveys such a potent evolutionary advantage that it outcompetes all previous clones. There is limited evidence for linear evolution in most advanced human cancers; instead, they are thought to evolve predominantly through a process of branching evolution, in which multiple clones can diverge in parallel from a common ancestor through the acquisition of different driver mutations. This results in common clonal mutations that form the trunk of the cancer’s evolutionary tree and are shared by all cells and subclonal mutations, which make up the branches and differ from cell to cell.

More recently, several other mechanisms of clonal evolution have been proposed, including neutral evolution, a type of branching evolution in which there are no selective pressures and evolution occurs by random mutations occurring over time that lead to genetic drift, and punctuated evolution, in which there are short evolutionary bursts of hypermutation.4,5

The CSC model

This model posits that the ability to form and sustain a cancer is restricted to a single cell type – the cancer stem cells – which have the unique capacity for self-renewal and differentiation. Although the forces of evolution are still involved in this model, they act on a hierarchy of cells, with stem cells sitting at the top. A tumor is derived from a single stem cell that has acquired a mutation, and the heterogeneity observed results both from the differentiation and the accumulation of mutations in CSCs.

Accumulated experimental evidence suggests that these models are not mutually exclusive and that they can all contribute to heterogeneity in varied amounts across different tumor types. What is clear is that heterogeneity and evolution are intricately intertwined in cancer development.1,2,6

An unstable genome

Heterogeneity and evolution are fueled by genomic alterations and the genome instability that they foster. This genome instability can range from single base pair substitutions to a doubling of the entire genome and results from both exposure to exogenous mutagens (eg, chemicals and ultraviolet radiation) and genomic alterations that have an impact on important cellular processes (eg, DNA repair or replication).

Among the most common causes of genome instability are mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway proteins or in the proofreading polymerase enzymes. Genome instability is often associated with unique mutational signatures – characteristic combinations of mutations that arose as the result of the specific biological processes underlying them.7

Genome-wide analyses have begun to reveal these mutational signatures across the spectrum of human cancers. The Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database has generated a set of 30 mutational signatures based on analysis of almost 11,000 exomes and more than 1,000 whole genomes spanning 40 different cancer types, some of which have been linked with specific mutagenic processes, such as tobacco, UV radiation, and DNA repair deficiency (Table 1).8