The impact of patient education on consideration of enrollment in clinical trials

Background Advances in clinical care depend on well-designed clinical trials, yet the number of adults who enroll is suboptimal.

Objective To evaluate whether providing brief educational material about clinical trials would increase willingness to participate.

Methods From October 23, 2015, through November 12, 2015, 1511 adults in the United States completed an anonymized electronic survey in a single-group, cross-sectional-design study to measure the impression of and willingness to enroll in a hypothetical cancer clinical trial before and after reading brief educational material on the topic.

Results Participants had a worse impression of and were less likely to enroll in a clinical trial before reading the material. Most participants (86.2%) noted that the educational material was believable, easy to understand (84.8%), and included information that was new (81.5%). After reading the material, the overall impression of clinical trials improved (mean standard deviation [SD], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.35-0.50). This improved outlook was greater among participants with a lower level of completed education (Pinteraction < .001). Education level effect was no longer significant after reading the document. Similar results were observed for likeliness of enrolling.

Limitations The study was not randomized, so it is uncertain if the increase in interest and likelihood of enrolling in a clinical trial was solely a result of the intervention; the findings may not be generalizable to a cancer-only cohort, and only English-speaking participants were included.

Conclusion Participants were receptive of educational material and expressed greater interest and likelihood of enrolling in a clinical trial after reading the material. The information had a greater effect on those with less education, but it increased the willingness of all participants to enroll.

Funding/sponsorship Supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. Julien Mancini was supported through mobility grants from Fondation ARC (SAE20151203703), ADEREM, and Cancéropôle PACA (Mobilités-2015). He has also received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under the REA grant agreement, and he received PCOFUND-GA-2013-609102 through the PRESTIGE Programme coordinated by Campus France.

Accepted for publication April 19, 2018

Correspondence Paul J Sabbatini, MD; sabbatip@mskcc.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e81-e88

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0396

Submit a paper here

Education level and baseline impression of and

willingness to enroll in a clinical trial

A lower level of education was associated with a decreased likelihood of previous trial participation or of knowing a trial participant, as well as with less awareness and inaccurate perceptions of clinical trials (Table 2).

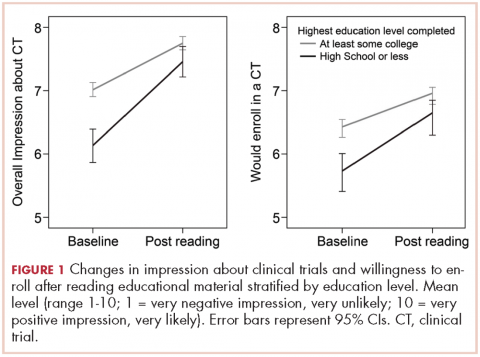

,Participants with a high school degree or less were more likely to have a worse impression of and were less likely to enroll in a future hypothetical clinical trial before reading the educational material (Figure 1). Multivariable analyses confirmed that lower education level was associated with lower baseline overall impression, regardless of other personal characteristics (Table 3). Lowest household income was also associated with a more negative impression of trials, whereas participants with a current medical condition and with previous contact with clinical trials had a more positive impression of them. The same effects were observed with likeliness to enroll in a future hypothetical clinical trial (correlated with the overall impression: r, 0.63; P < .001), except that the negative effect of female gender was statistically significant (Table 3).

Posteducation impression of and willingnes to enroll

willingness to enroll in a clinical trial

The brief educational material was mostly considered believable (86.2%), easy to understand (84.8%), and included information that was new to participants (81.5%; Table 2). Participants with a high school diploma or less more often noted that the material provided them with new information, but they also reported more difficulties in fully understanding and believing the information. Overall, however, few participants found the information difficult to understand (4.6%) or hard to believe (1.8%; Table 2).

Most participants had an improved overall impression of clinical trials (standardized mean difference, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.35-0.50; P < .001) after reading the educational material. This increase was higher among participants with a lower completed level of education (Figure 1; standardized mean difference, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45-0.79; Pinteraction < .001). The same effects were observed for likeliness to enroll in a future hypothetical clinical trial (P < .001; Figure 1).

After reading the informational statement, education level effect was no longer significantly associated with the overall impression of clinical trials (P = .23) and willingness to enroll in a clinical trial (P = .34), whereas the effects of income, current medical condition, and previous engangement with clinical trials remained statistically significant (Table 3).

Remaining challenges

Regarding hypothetical participation in a future clinical trial after a cancer diagnosis, the most critical concerns were related to side effects and the uncertainty of insurance coverage (Figure 2).10 The lack of understanding of clinical trials was the least critical concern; however, it was significantly higher among participants with a lower completed level of education. These participants also expressed more critical concerns about feeling like a “guinea pig,” inconvenient trial location, and the frequent visits needed.

Discussion

Findings from this survey demonstrated that providing brief educational material about cancer clinical trials was associated with a more favorable impression of clinical trials and higher interest in trial participation. Furthermore, as far as we can ascertain, this is the first report showing how a simple intervention such as this may help close the knowledge gap on clinical trials among people of different educational backgrounds. Although most respondents in this interventional survey noted an increased willingness to consider participation in a clinical trial after reading the educational material, those with a lower level of education and knowledge about clinical trials received the most benefit. Previous participation in a clinical trial was also strongly associated with the impression of and willingness to enroll in a trial, both before and after reading the statement.11

Most of the interventions evaluated to date12 have focused on patients who are faced with having to decide whether to participate in a clinical trial2,3 or on very specific populations, such as select ethnic communities.13,14 However, it may be beneficial to provide simple, concise educational information about clinical trials to the general population, especially to those with minimal education. Although level of education concerns the minority of our sample (19%) sourced from an online panel, in the 2015 Current Population Survey, 41% of US participants aged 25 and older had not reached college education.15 Those with a lower level of education have reported a general lack of familiarity with clinical trials and were more likely to have inaccurate perceptions about trials. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown the lack of awareness and knowledge of clinical trials in this population.5,16,17 Our findings suggest that this knowledge gap can be reversed through a simple educational intervention and result in an increased willingness to participate.

The provision of information on clinical trials was positively associated with the 2 outcomes analyzed – improved impression of clinical trials and increased likelihood to enroll in a hypothetical trial. Such improvement might not translate to improved accrual,18 but it is a step toward closing the overall knowledge gap related to clinical trials and increasing the number of people who would consider trial participation. The lack of awareness of clinical trials has been reported as a legitimate explanation for why participation rates are lower in less-educated patient populations.19,20 This brief educational intervention is a simple, technology-sparing way to increase clinical trial awareness in the general population. In a similar survey, most physicians who reviewed an educational statement noted they were likely to use it with patients.21Less-educated patients, those who lived outside of urban areas, and those with lower household incomes were most concerned about trial location and the frequent visits needed when participating in a trial (Figure 2). Living in a nonurban area was not associated with participant impression of clinical trials or willingness to enroll in a trial. However, rural residency may be a barrier to enrollment depending on distance to the hospital22 and out-of-pocket expenses related to travel.23 Some comprehensive cancer centers, such as MSK, have developed alliances with community centers24 as a means of overcoming geographical barriers and increasing clinical trial participation rates.

Another concern shared by most respondents was the uncertainty in insurance coverage and potential out-of-pocket costs related to care. Lower household income, unlike location of residence and lack of insurance, was significantly associated with negative impressions of clinical trials and lower willingness to enroll in a trial, even after adjusting for education level. Cancer patients with higher financial burden have reported more attitudinal barriers, even after accounting for the negative effect of lower education level.25 Recent studies have also discussed the negative impact of lower income on cancer clinical trial participation,19,20,26,27 and new attention has been paid to the negative financial implications or “financial toxicity” of participating in a trial.23,28

White and older survey participants showed similar interest in clinical trial participation after accounting for other characteristics. There is growing evidence that outcome differences attributed to race may in fact be more dependent on socioeconomic status.8 A recent study among breast cancer patients showed that low socioeconomic status, but not race, was associated with decreased participation in clinical trials.29,30 Previous findings have also indicated that interest in clinical trials and barriers to enrollment among older, less-educated patients31 are often related to ineligibility, comorbidity, or communication difficulties.

Among our participants, the fear of side effects also was a common attitudinal barrier to clinical trial participation, as has been reported in previous studies.3,20 However, contrary to one previous study,20 this fear was not significantly increased among our less-educated participants.

Less-educated participants also reported more difficulties in understanding the information they were provided with, and they remained more concerned about being treated like “guinea pigs.” These concerns are consistent with other results showing that decisional conflict about clinical trial participation among patients with a high school diploma or less remained high even after they had received a National Cancer Institute text as pre-education material.3