Enhancing communication between oncology care providers and patient caregivers during hospice

Background When patients enroll in hospice, they and their close family and friends (ie, caregivers) often report feeling a sense of abandonment because of the break in routine communication with their oncology clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]).

Objective To assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients in hospice care.

Methods Caregivers of patients with cancer who enrolled in home hospice were eligible to participate. The intervention consisted of supportive phone calls from their oncology clinicians, an optional clinic visit, and a bereavement call. The primary outcome was feasibility, defined as >70% of caregivers receiving >50% of phone calls and >70% of caregivers completing >50% of questionnaires. We also assessed caregiver satisfaction with the supportive intervention, stress, decision regret, and perceptions of end-of-life care.

Results Of 38 eligible caregivers, 6 declined participation, 7 could not be reached, and 25 (81%) enrolled in the study. Of those, 22 caregivers were evaluable after 2 patients died before the intervention began and 1 caregiver withdrew. Oncology clinicians completed 164 of the expected 180 calls (91%) to caregivers. The majority of the calls were made by the RN or NP. Caregivers completed 78 of the expected 99 (79%) questionnaires. All of the caregivers received >50% of scheduled phone calls, and 73% completed >50% of the questionnaires. During exit interviews, caregivers reported satisfaction with the intervention.

Limitations Single-institution, small sample size

Conclusions This intervention proved feasible because caregivers received the majority of planned phone calls from oncology clinicians, completed the majority of study assessments, and reported satisfaction with the intervention. A randomized trial to evaluate the impact on caregiver outcomes is warranted.

Funding Supported on NIH T32CA071345

Accepted for publication January 31, 2018

Correspondence Jessica R Bauman, MD; Jessica.Bauman@fccc.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e72-e80.

2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0391

Related articles

The need for decision and communication aids: a survey of breast cancer survivors

Submit a paper here

Results

Baseline characteristics

During March 2014-June 2015, we enrolled caregivers of patients with advanced cancer from 5 participating disease centers: thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological malignancy. We screened 123 patients to determine the eligibility of their caregivers (Figure 2). Of 38 eligible caregivers, 7 could not be reached, 6 declined participation, and 25 enrolled in the study (81% enrollment rate). Of the 25 caregivers who enrolled, 3 withdrew – 2 because the patients they were caring for died before the intervention began, and 1 who withdrew from the study because the family wanted less contact with the oncology clinician/s. Thus, we had data for 22 caregivers for our feasibility evaluation. One caregiver stopped study assessments after 3 months because the patient dis-enrolled from hospice. Median time from the patients’ hospice enrollment to caregiver study enrollment was 3 days (range, 1-9). Median time from study enrollment to patient death was 36 days (range, 2-135). Patients were receiving care from 10 different hospice agencies.

All of the patients had metastatic cancer, and 64% were women (Table 1).

,Most of the caregivers were white (n = 18, 90%) and women (n = 12, 55%). The majority were the patient’s spouse (n = 12, 60%) or child (n = 6, 30%), and they lived with the patient (n = 16, 80%). Many of the caregivers had other responsibilities in addition to caring for the patients, including part- or full-time work (n = 10, 50%) or caring for others in addition to the patient (n = 10, 50%).

Feasibility

Over the study period, oncology clinicians completed 164 of 180 possible phone calls (91%). All 22 caregivers received >50% of the phone calls. Caregivers completed 78 of 99 possible questionnaires (79%), and 16 of 22 completed >50% of the questionnaires (73%). None of the caregivers/patients wanted to schedule the optional visit with an oncology clinician that was offered as part of the intervention; however, 5 patients had a clinic visit after hospice enrollment. In addition, 2 oncologists visited a patient and caregiver at home. All caregivers received bereavement contact from the oncology team.

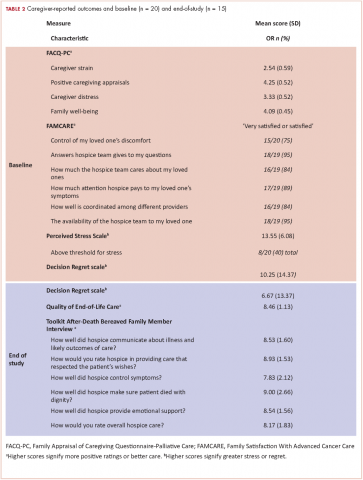

Caregiver-reported outcomes

In all, 20 of the 22 enrolled caregivers completed baseline measures (Table 2), and they all chose to complete questionnaires by e-mail. Caregivers’ attitudes toward caregiving and satisfaction with hospice services were overall positive. They reported high mean scores on the 2 domains on the FACQ-PC of positive caregiver appraisal (mean, 4.25; SD, 0.52) and family well-being (mean, 4.09; SD, 0.45). The majority of caregivers (75%-95%) reported they were satisfied or very satisfied with various dimensions of hospice care based on the FAMCARE questionnaire.

Overall, caregivers reported moderate levels of stress (mean, 13.55; SD, 6.08) based on the PSS scores. Of the 20 caregivers who completed the baseline measures, 8 had clinically meaningful stress, and stress was numerically higher in female caregivers than in their male counterparts, but it did not reach statistical significance (55% vs 22%, P = .197). Finally, at baseline, caregivers indicated relatively low levels of decisional regret about enrolling in hospice, although there was considerable variation (mean, 10.25; SD, 14.37).

We conducted exit interviews with 15 caregivers because we were not able to reach 6 of the original 21 (Table 2). Caregivers rated hospice services highly for communication, symptom control, emotional support, and overall care. They also rated quality of death highly (mean, 8.46; SD 1.13). Regret was lower at the end of the study, but this did not reach statistical significance (baseline mean 9.29; end of study mean 3.57; P = .161).

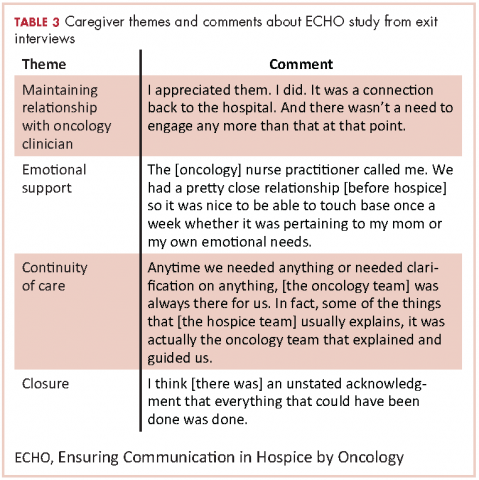

In the recorded exit interviews, all of the caregivers responded they were satisfied with the phone calls. Two caregivers commented that they would have preferred the calls were more scheduled or at more suitable times. Overall, they described the phone calls as excellent, supportive, responsive, comfortable, and appreciated. All caregivers reported contact with the oncology team after the patient died, but one caregiver was disappointed she was only contacted by the nurse practitioner and not the oncologist. Participants did not feel as if there were other ways that the oncology team could have been helpful for them while their loved one was in hospice.

Table 3 highlights other representative comments from the exit interviews.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who are receiving hospice care. Despite the challenges of oncology clinicians delivering an intervention to caregivers during hospice, we found this intervention was feasible and acceptable. Although the transition to hospice can be stressful, caregivers reported high satisfaction with hospice care and the quality of the patient’s death. In exit interviews, they also reported high satisfaction with the intervention and appreciation for maintaining their relationship with the oncology team. It is worth noting that no caregiver requested the optional clinic visit after hospice enrollment, and most caregivers were not seen again in clinic after hospice enrollment.