Durable response to pralatrexate for aggressive PTCL subtypes

Accepted for publication September 13, 2017

Correspondence Jakub Svoboda, MD; jakub.svoboda@uphs.upenn.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e102-e105

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0369

Related articles

VIDEO: How to prepare PTCL patients for transplant

Submit a paper here

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of mature T- and natural killer-cell neoplasms that comprise about 10%-15% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States.1,2 The development of effective therapies for PTCL has been challenging because of the rare nature and heterogeneity of these lymphomas. Most therapies are a derivative of aggressive B-cell lymphoma therapies, including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vinicristine, prednisone) and CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vinicristine, etoposide, prednisone).1 Many centers use autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant in this setting,1 but outcomes remain poor and progress in developing effective treatments has been slow.

Pralatrexate is the first drug to have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for treating patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL.3 As a folate analog metabolic inhibitor, pralatrexate competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase and reduces cellular levels of thymidine monophosphate, which prevents the cell from synthesizing genetic material and triggers it to undergo apoptosis.4 The agency’s approval of pralatrexate was based on results from the PROPEL study, which is possibly the largest prospective study conducted in patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL (109 evaluable patients).2 Findings from the study showed an overall response rate (ORR) of 29%, and a median duration of response (DoR) of 10 months.2

Pralatrexate is administered intravenously at 30 mg/m2 once weekly for 6 weeks of a 7-week treatment cycle. It is generally continued until disease progression or an unacceptable level of toxicity.2 Alternative dosing schedules have been described, including 15 mg/m2 once weekly for 3 weeks of a 4-week treatment cycle for cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.5

,In this case series, we examine the outcomes of 2 patients with particularly aggressive subtypes of PTCL who were treated with pralatrexate. The significance of this report is in describing the long duration of response and reporting on a PTCL subtype – subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, alpha/beta type – that was underrepresented in the PROPEL study and is underreported in the literature.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

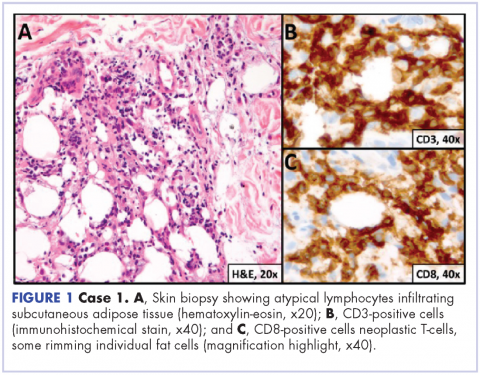

A 23-year-old Asian American man with a medical history of osteogenesis imperfecta presented to Emergency Department at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania with bilateral lower extremity edema, low-grade fevers, a weight loss of 25 lb, and flat hyperpigmented scaly skin patches across his torso. Symptoms had started manifesting around five months prior to the visit. A punch biopsy of a skin lesion revealed skin tissue with focal infiltrate of small- to medium-sized, atypical lymphocytes infiltrating subcutaneous adipose tissue (panniculitis-like) and adnexa. Immunohistochemical stains showed that the abnormal lymphocytes were positive for CD3, CD8, perforin, granzyme B, TIA-1 (minor subset), and TCR beta; and negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30. Proliferation index (Ki67) was 70%. The findings were consistent with primary subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, alpha/beta type (Figure 1). A staging positron-emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) scan demonstrated stage IVB lymphoma with subcutaneous involvement without nodal disease.

He was initially treated with aggressive combination regimens including EPOCH (etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin) and ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), but he had no response and his disease was primary refractory. Because of his osteogenesis imperfecta, he was not a candidate for allogenic stem cell transplant.

He responded to hyperCVAD B combination therapy (methotrexate and cytarabine), but the course was complicated by cytarabine-induced ataxia and dysarthia. He was then treated with 3 months of intravenous alemtuzumab without response. Intravenous methotrexate (2,000 mg/m2) was then used for 3 cycles, but this exacerbated his previous cytarabine-induced neurological symptoms and resulted in only partial response with persistent fluorine-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) avid lesions on a subsequent PET–CT scan.

At that point, the patient was started on pralatrexate at 15 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks on a 4-week cycle schedule. This was his fifth line of therapy and at 16 months from his initial diagnosis. This dosage was continued for 6 months, and he tolerated the therapy well. He reported no exacerbations of his dysarthia, and by the second month, he had achieved clinical and radiographic remission with complete resolution of B symptoms (fevers, night sweats, and weight loss). The dosing was modified to 15 mg/m2 every 2 weeks for 3 months. A whole body PET–CT scan showed resolution of previously FDG avid lesions.

The patient was then continued on 15 mg/m2 pralatrexate every 3 weeks for 1 year and he has been maintained on once-a-month dosing for a second and now third year of therapy. He continues to tolerate the therapy and remains disease free at nearly 2 years since starting pralatrexate.