Management of polycythemia vera in the community oncology setting

Patients with the chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm polycythemia vera have shortened survival and often experience disease-related symptoms that negatively affect quality of life. Consequently, there is a demonstrable need for early diagnosis of polycythemia vera, followed by long-term, responsive, evidence-based disease management. The diagnostic and management landscape for polycythemia vera continues to improve, but gaps remain in diagnostic and treatment strategies. The diagnosis of polycythemia vera is based on World Health Organization criteria, and treatment goals for the condition include modifying the risk of cardiovascular and hemorrhagic events, reducing the risk of fibrotic and/or leukemic disease transformation, and alleviating polycythemia vera–related symptoms. The current treatment strategy for polycythemia vera is for all patients to receive aspirin and phlebotomy, with a hematocrit goal of <45%. Some patients may also benefit from cytoreductive therapy, typically with hydroxyurea. For those patients who become resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea, ruxolitinib is currently the only approved treatment option. This review provides community-based oncologists and other clinicians with an overview of current diagnostic and management strategies for polycythemia vera.

Accepted for publication April 28, 2017

Correspondence Michael R Grunwald, MD;

michael.grunwald@carolinashealthcare.org

Disclosures Dr Grunwald has served as a consultant, participated in advisory boards, and received research funding from Incyte Corp, the maker of ruxolitinib, a treatment option for polycythemia vera. Dr Scola has served on a speakers bureau for and is a stockholder of Incyte Corp. Dr Miller has served on advisory boards and speakers bureaus for, and received institutional research funding from, Incyte Corp and Novartis. Dr Onitilo has no conflicts to disclose. The authors received writing assistance from Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC, which was funded by Incyte Corp.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(4):e195-e203

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0349

Submit paper here

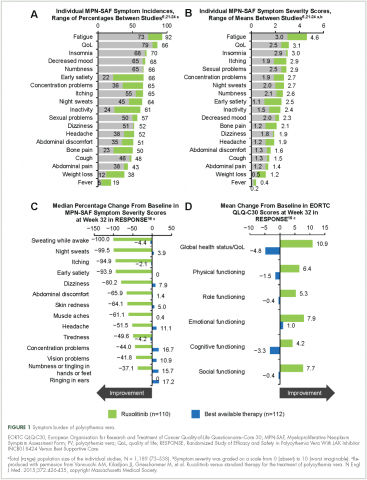

Symptoms and quality of life

Symptoms of polycythemia vera vary in severity, and patients often fail to attribute symptoms to the disease.20 Moreover, clinicians may underestimate a patient’s true disease burden or the effect it has on QoL.20 Point-of-care metrics, such as the MPN Symptom Assessment Form (MPN-SAF), were developed to aid in identifying and grading symptom burden. Studies using this metric have reported fatigue as the most common and most severe symptom (incidence, 73%-92%), with a variety of other symptoms also affecting a majority of patients (Figure 1).6,21-24 Although fatigue, pruritus, and a higher MPN-SAF total symptom score are significantly correlated with reduced QoL,22,25 the recent MPN Landmark survey suggests that even patients with low symptom severity scores have a reduction in their QoL.6 This study also highlighted that polycythemia vera can adversely affect multiple aspects of daily living: 48% of patients reported disease interfering with daily activities; 63% with family or social life; and 37% with employment, feeling compelled to work reduced hours.6

Splenomegaly is a common feature of polycythemia vera, affecting an estimated one in three patients, which may result in discomfort and early satiety.4

Identification and diagnosis

Most patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera are between the ages of 60 and 76 years,3-5 although about 25% are diagnosed before age 50.4 Tefferi and colleagues reported in a retrospective study that common features at presentation include JAK2 mutations (98%), elevated hemoglobin (73%), endogenous erythroid colony growth (73%), white blood cell count of >10.5 × 109/L (49%), and platelet count of ≥450 × 109/L (53%).4 In that same study, about a third of patients presented with a palpable spleen or polycythemia vera–related symptoms, including pruritus and vasomotor symptoms. However, many patients were asymptomatic at presentation, diagnosed incidentally by abnormal laboratory values.4 Patients can present with vascular thrombosis, occasionally involving atypical sites (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, other abdominal blood clots),26 thus, a heightened awareness and testing for JAK2 mutations may be appropriate in the evaluation of such individuals.

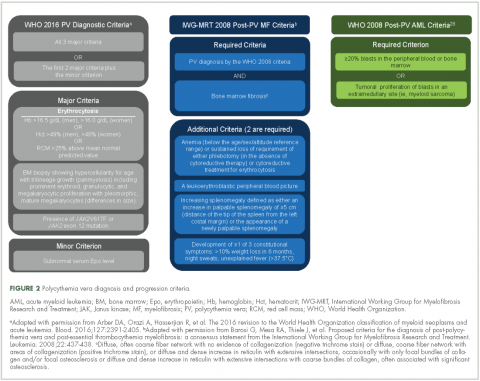

Evidence suggests many clinicians may not rigidly apply the WHO diagnostic criteria to establish a diagnosis.1,27,28 A recent retrospective claims analysis showed that only 40% of 121 patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera met the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria, and for some patients, the diagnosis was based solely on the presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation.29 One should be aware of individuals with “masked” polycythemia vera, who may present with characteristic polycythemia vera features but have hemoglobin levels below those established by the WHO in 2008, typically owing to iron deficiency and/or a disproportionate expansion of plasma volume.30 To improve polycythemia vera diagnosis, the WHO diagnostic criteria were updated in 2016 with reduced hemoglobin diagnostic thresholds (Figure 2).1

Management strategy

Treatment goals

The primary polycythemia vera–treatment goals are to reduce the risk of cardiovascular, thrombotic, and hemorrhagic events; reduce the risk of fibrotic and/or leukemic transformation; and alleviate polycythemia vera–related symptoms.11,31

Traditional treatment options

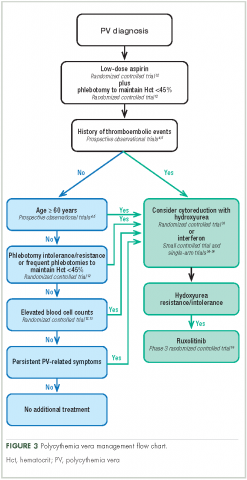

Aspirin. To reduce the risk of death from cardiovascular events, patients with polycythemia vera should receive low-dose aspirin32 and undergo phlebotomy to maintain a target hematocrit <45%, as established by the ECLAP and CYTO-PV trials (Figure 3).4,5,12,13,16,32-36 Higher doses of aspirin (ie, 325 mg 2 or more times a week) are associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.37 Low-dose aspirin is generally well tolerated; however, patients with extreme thrombocytosis may develop bleeding as a consequence of a well-described, thrombocytosis-associated acquired von Willebrand disease.11,38

Phlebotomy. This procedure is generally tolerated by most patients, although it can occasionally engender extreme anxiety in some patients39 and may promote clinical manifestations of iron deficiency, including restless leg syndrome,40 impaired cognition, and worsening of fatigue.41 In the CYTO-PV study, 28% of patients with a target hematocrit 45%-50% discontinued phlebotomy treatment, although the percentage that discontinued because of poor tolerance was not reported.12 To avoid potential complications in patients with underlying cardiovascular disease, smaller-volume phlebotomies are often pursued.42

Cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy with hydroxyurea or interferon (IFN) is recommended for high-risk patients (ie, those with a history of thrombosis or older than 60 years) as well as those with intolerable symptoms, progressive splenomegaly, or a burdensome phlebotomy requirement.11,31 Hydroxyurea is the typical first-line cytoreductive therapy11 based on clinical benefit,33,43 low cost, and feasibility of long-term treatment.33

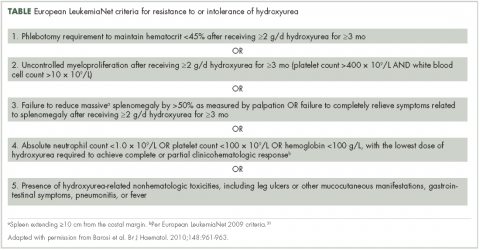

Most patients benefit from long-term treatment with hydroxyurea; however, 25% develop resistance to or intolerance of hydroxyurea therapy.44 Intolerance typically manifests as leg ulcers or other mucocutaneous toxicity, gastrointestinal side effects, or fever.44 Resistance to hydroxyurea is defined as failure to achieve phlebotomy independence, persistent leukothrombocytosis or splenomegaly despite adequate doses of hydroxyurea, or inability to deliver the drug owing to dose-limiting cytopenias. The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) formally codified and published a definition of hydroxyurea resistance/intolerance45 (Table), which can be used to identify patients at high risk of poor outcomes.44 In a retrospective chart review of 261 patients with polycythemia vera, those meeting the ELN definition of hydroxyurea resistance had a 5.6-fold greater risk of mortality and a 6.8-fold increased risk of fibrotic and/or leukemic disease transformation.44

The use of IFN-α and pegylated variants are associated with clinical benefit, including normalization of blood counts, reduction of splenomegaly, symptom mitigation, and reduction in JAK2 V617F allele burden.46 However, poor tolerance46 and an inconvenient route of administration often preclude the long-term use of these agents. Adverse events associated with IFN-α include chills, depression, diarrhea, fatigue, fever, headache, musculoskeletal pain, myalgia, nausea, and weight loss.46 In clinical trials, recombinant IFN-α discontinuation rates within the first year of administration were as high as 29% and may have been dose dependent.46

Traditional treatment options may not effectively alleviate polycythemia vera–related symptoms.23,47 Two prospective studies failed to show an improvement in patient-reported MPN-SAF scores after treatment with hydroxyurea, aspirin, phlebotomy, IFN-α, busulfan, or radiophosphorus,23,47 and symptoms may worsen with the use of IFN-α.47