Prescriber adherence to antiemetic guidelines with the new agent trifluridine-tipiracil

Background In 2015 alone, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 18 cancer drugs, but to our knowledge, few studies, if any, have examined prescribers’ adherence to antiemetic guidelines as new chemotherapy agents become available. This issue is important because poor adherence to antiemetic guidelines has been shown in previous studies to have a negative impact on the control of nausea and vomiting. Here we report on antiemetic practices and outcomes for trifluridine-tipiracil, a drug newly approved in 2015.

Objective To test the hypothesis that patients prescribed a newly available chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil, are at risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting because of providers’ poor adherence to antiemetic guidelines.

Methods All patients who received their first dose of trifluradine-tipiracil for metastatic colon cancer in 2015 were included in this retrospective, single-institution study of pretreated patients. The study time frame was the 2015 calendar year: 9 months before the drug was approved in September 2015, when patients received the medication through a compassionate-use program, and the 3 months immediately after drug approval. First-cycle antiemetic prescribing was examined for adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines (v1.2015) and categorized as guideline adherent, non–guideline-adherent/aggressive (received more prophylaxis than called for), and non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive (including no antiemetics).

Results Of the 44 patients in this study, 28 (64%) had had nausea and vomiting with previous chemotherapy. With the first cycle of trifluridine-tipiracil, 25 patients (57%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 42%, 70%) were prescribed prophylactic antiemetics in a guideline-adherent manner; 15 (34%; 95% CI: 22%, 49%) in a non–guideline-adherent/aggressive manner; and 4 (9%; 95% CI: 4%, 21%) in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner. In guideline-adherent patients, rates of nausea and vomiting were 52% and 24%, respectively. In non–guideline-adherent/aggressive patients, those rates were 33% and 27%, respectively. In both the aforementioned groups, a total of 2 patients received interim care for nausea and vomiting. No nausea or vomiting was reported among non–guideline-adherent/less aggressively managed patients.

Limitations Single-institution, retrospective study of a small group of patients

Conclusions Poor adherence to antiemetic guidelines was common. However, because adherence was not consistently associated with better control of nausea and vomiting, clinical judgment should complement guideline adherence when prescribing trifluridine-tipiracil and other newly approved cancer drugs.

Accepted for publication November 3, 2016

Correspondence Aminah Jatoi, MD; Jatoi.aminah@mayo.edu

Disclosures All of the authors are with the Mayo Clinic, which has received research grants from Taiho Oncology, the maker of trifluridine-tipiracil.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(3):e142-e146

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0314

Related articles

Omission of dexamethasone from antiemetic treatment for highly emetogenic chemotherapy in breast cancer patients with hepatitis B infection or diabetes mellitus

APF530 for nausea and vomiting prevention following cisplatin: phase 3 MAGIC trial analysis

A modified olanzapine regimen for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

Submit a paper here

Data reporting

The primary goal of this study was to report the percentage of patients who had been prescribed a first-cycle antiemetic prophylaxis regimen concordant with NCCN guidelines. Secondary goals included reporting the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the use of rescue antiemetics other than those prescribed up front, the need for an unplanned medical encounter to address nausea and vomiting, and change in antiemetic prescribing before the second chemotherapy cycle. Confidence intervals were calculated with JMP Pro 10.0.0. This study was too limited in sample size to assess sex-based differences in outcomes.

Results

Demographics

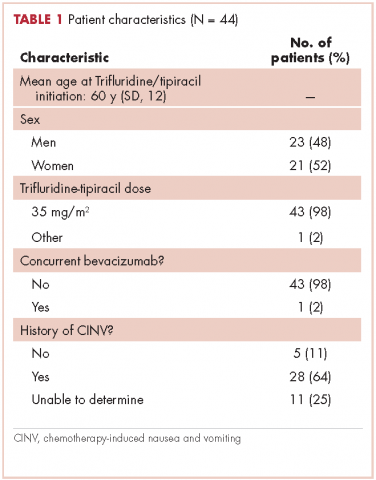

This report focuses on 44 patients who received first-cycle trifluridine-tipiracil during the first calendar year of the drug’s FDA approval. All patients had metastatic colorectal cancer and had previous exposures to other chemotherapy agents (Table 1). Of note, 28 patients (64%) had experienced CINV before starting trifluridine-tipiracil and all these patients had been heavily pretreated with multiple lines of chemotherapy.

Guideline adherence

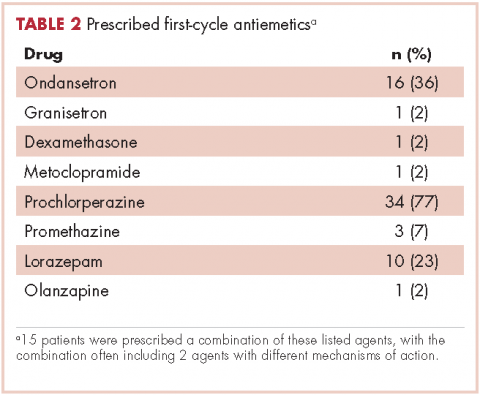

Patients were most commonly prescribed prochlorperazine and ondansetron prophylaxis for CINV before the first chemotherapy cycle of trifluridine-tipiracil (Table 2): 15 patients were prescribed combination antiemetic therapy, typically two of the most commonly prescribed single agents with different mechanisms of action. Twenty-five patients (57%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 42%, 70%) were prescribed antiemetics in a manner consistent with guidelines; 15 (34%; 95% CI: 22%, 49%) were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive manner (received more prophylaxis than called for); and 4 (9%; 95% CI: 4%, 21%) were prescribed them in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner.

Clinical outcomes based on guideline adherence

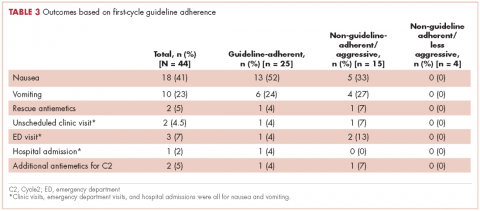

In guideline-adherent patients, first-cycle nausea and vomiting occurred in 13 patients (52%) and 6 patients (24%), respectively, with 1 patient requiring an unscheduled clinic visit and another an emergency department visit and hospital admission – all for nausea and vomiting (Table 3). In non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive patients, those symptoms occurred in 5 patients (33%, nausea) and 4 patients (27%, vomiting), with 1 patient requiring a clinic visit and emergency department visit and another an emergency department visit – again, all for nausea and vomiting. In non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive patients, no nausea or vomiting was reported.

Discussion

This study examined adherence to antiemetic guidelines in the setting of a soon-to-be-approved or newly approved antineoplastic agent. As hypothesized, a substantial proportion of patients (43% in this study) were prescribed antiemetics in a nonadherent manner with respect to guidelines, thus identifying the period shortly before and after FDA approval as a particularly vulnerable interval with respect to antiemetic guideline adherence. It is possible that our institution’s practice of testing novel chemotherapy agents for the treatment of colorectal cancer prompted a heightened awareness of potential adverse events, leading to greater guideline adherence than might have occurred in other settings and resulting in judicious straying from guideline adherence only when appropriate.12-14 Thus, these high rates of poor adherence may in fact represent an underestimate of what one might see in other clinical practices; and, similarly, these rates of symptom control might also be more favorable than those one might see in other clinical practices. To our knowledge, antiemetic prescribing practices with newer chemotherapy agents have not been explored before now, and our data underscore a clear need to do so – particularly during this limited interval when health care providers begin to prescribe new chemotherapy agents for the first time.

It is worth noting that despite the high rates of guideline nonadherence, rates of nausea and vomiting seemed to be comparable in patients prescribed antiemetics in a guideline-adherent manner and those prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/aggressive manner.A small number of patients in both the guideline-adherent and non–guideline-adherent/aggressive groups required rescue medications, unscheduled medical visits for nausea and vomiting, and additional antiemetics during the second cycle of chemotherapy. Of note,none of those interventions occurred in patients who were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner. These findings might reflect the fact that the patients had proven themselves to be at risk for nausea and vomiting with previous chemotherapy. Before they became candidates for trifluridine-tipiracil, patients had been heavily pretreated with other chemotherapy agents, most had experienced CINV, and many were therefore highly predisposed to nausea and vomiting. These observations underscore the fact that guidelines – even those that are well accepted and widely used – should be implemented in concert with good clinical judgment.10,11 This study has shortcomings, most notably its small sample size. However, had we extended our study beyond 3 months of the FDA approval to include more patients, our findings would have reflected more experienced prescribing practices and we thereby would have deviated from our primary goal of assessing antiemetic prescribing practices with only recently-approved and available chemotherapy agents. In this context, this limited sample size aptly serves a primary role of capturing outcomes within a fleeting but critical interval of new drug availability.In summary, this study found a notable rate of poor guideline adherence when prescribing antiemetics for trifluridine-tipiracil, a new chemotherapy agent of low emetogenic potential. Although the resultant rates of nausea and vomiting suggest that good clinical judgment might have influenced whether or not guidelines were adhered to, these findings nonetheless underscore the need to assess adherence to antiemetic guidelines when new chemotherapy drugs become available and potentially to put in place institutional infrastructure rapidly to promote improved adherence. Such an assessment should be deliberate, formalized, and prompt within individual oncology clinics and cancer centers after a new cancer drug becomes available. In conjunction with clinical judgment, such measures might lead to improved symptom control.