Comprehensive assessment of cancer survivors’ concerns to inform program development

Background Health care professionals are caring for a growing number of diverse cancer survivors, often in an environment in which resources are limited. The identification of the most salient concerns of survivors is essential for targeted program planning and for providing quality care.

Objective To prioritize survivors’ physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns, and to assess the perceived importance of those needs and the extent to which staff were attentive to them. To demonstrate the usefulness of a broad survey approach.

Methods Surveys that used a quality-of-life framework to assess concerns were mailed to a convenience sample of 2,750 cancer survivors. Logistic regression models were used to identify associations with the 12 most highly rated moderate or high concerns.

Results A total of 1,005 surveys were returned for a 37% response rate. Fears of the cancer recurring (n = 486, 51%) and developing a new cancer (n = 459; 47.5%) were the 2 most prevalent concerns among respondents. Young age, unemployment, race other than white, and female sex were associated with greater moderate- or high-level concerns throughout the cancer trajectory. Spiritual and social concerns were least often attended to by staff.

Limitations Use of a nonvalidated survey and cross-sectional approach limited our ability to explore how concerns may change over the cancer trajectory.

Conclusion A comprehensive needs assessment is a valuable tool to inform survivorship and supportive care program development by highlighting common concerns, demographic and medical factors associated with specific concerns, and timing of moderate-or high-level concerns along the cancer trajectory.

Funding/sponsorship None

Accepted for publication February 21, 2017

Correspondence Susan R Mazanec, PhD, RN, AOCN; susan.mazanec@case.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(3):e155-e162

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0338

Related articles

Adolescent and young adult perceptions of cancer survivor care and supportive programming

Survivorship care planning in a comprehensive cancer center using an implementation framework

Submit a paper here

To identify the most prevalent concerns, ratings for concerns were recoded into no concern (rated as 0), low concern (1 or 2), and moderate/high concern (3, 4, or 5). Since our interest was in the moderate and high concerns, the responses were dichotomized into moderate/high concerns and all other levels. Logistic regression models were then used to identify associations between a set of survivor characteristics or covariates (age, sex, living status, marital status, employment status, cancer type, and time since treatment) with the 12 most highly rated moderate/high concerns. All the analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS 20 and Stata 13.0

Results

Respondents

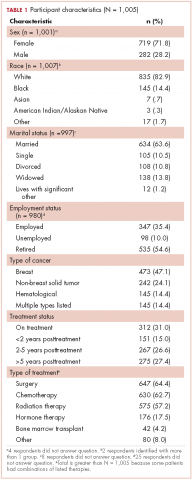

A total of 1,005 surveys were returned for a 37% response rate. Forty-two patients responded by telephone. The mean age of respondents was 64.9 years (range, 22-98; SD, 12.8). The typical respondent was female, white, and married (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of the respondents (n = 240) reported living alone. Although about 47% of respondents (n = 473) reported a breast cancer diagnosis, more than 17 cancers were identified, and 14% of respondents (n = 145) listed multiple diagnoses. About a third of respondents were receiving treatment when they completed the survey.

Just under half of the respondents (n = 498) reported using community resources for support and information about cancer, and 29.5% (n = 296) sought information on the internet during their cancer experience. The most commonly used community resources were The Gathering Place, a local organization offering free supportive programs and services to individuals with cancer and their families (n = 167), and the American Cancer Society (n = 138). Of the 496 respondents who reported accessing hospital resources, most (n = 322) said they used information that their health care team recommended. Other supportive options were used to a lesser degree: support groups (n = 92), chemotherapy and radiation therapy classes (n = 129), and supportive/educational programs offered by the cancer center (n = 27). Most of the respondents (n = 822, 88.6%) preferred to have their follow-up care remain with their cancer care team 1 year after treatments are completed. Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 601, 64%) cited being seen at the cancer center for follow-up care as the most important factor in considering follow-up care.

Concerns In determining whether the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer skewed the study results, it was determined that median scores differed significantly in only four concerns. Compared with respondents without breast cancer, respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly lower scores for concerns related to fatigue (P <.001) and sexual issues/intimacy (P = .001). Respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly higher scores than respondents without breast cancer for concerns related to genetic counseling (P = .001) and fear of developing a new cancer (P = .010).

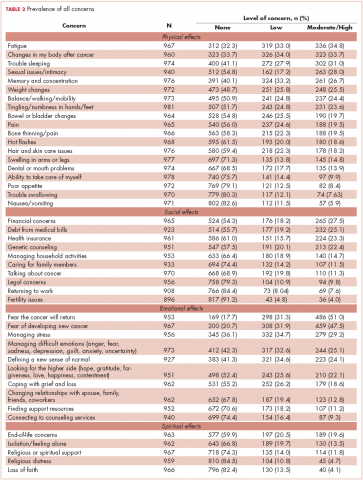

Fears of the cancer returning and developing a new cancer were the two most prevalent concerns, identified by 51% (n = 486) and 47.5% (n = 459), respectively (Table 2). Physical concerns, rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample, were fatigue (n = 336, 34.8%), changes in [the] body after cancer (n = 323, 33.7%), trouble sleeping (n = 302, 31.0%), sexual issues/intimacy (n = 263, 28.0%), memory and concentration (n = 261, 26.7%), and weight changes (n = 248, 25.5%). The most prevalent moderate/high social concerns were related to finances (n = 265, 27.5%) and debt from medical bills (n = 232, 25.1%). Managing stress (n = 279, 29.2%) and difficult emotions (n = 244, 25.1%) were prevalent moderate/high emotional concerns. Spiritual concerns were less often rated as moderate/high concerns. Having a breast cancer diagnosis was not significantly related to the number of reported moderate to high concerns (P = 1.00).

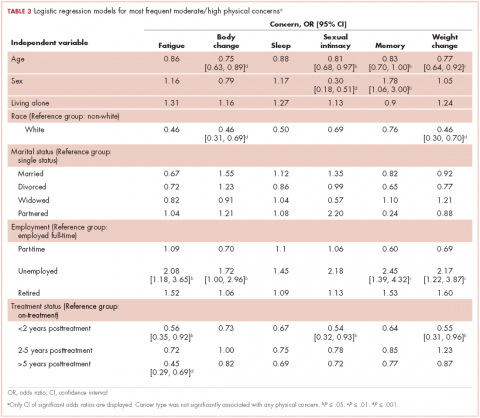

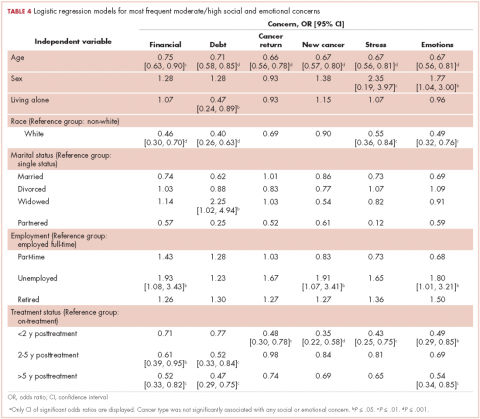

Variables associated with the 12 most frequent moderate/high concerns are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Age was associated with the most moderate/high concerns. With every decade of age, the odds of having the following moderate/high concerns decreased: bodily changes after cancer (odds ratio [OR], 0.75), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.81), memory and concentration (OR, 0.83), weight changes (OR, 0.77), financial (OR, 0.75), debt (OR, 0.71), cancer returning (OR, 0.66), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.67), managing stress (OR, 0.67), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.67).

Female sex was associated with lower odds of having a concern about sexual intimacy (OR, 0.30) and increased odds of having concerns related to memory and concentration (OR, 1.78), managing stress (OR, 2.35), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.77). Race was another demographic characteristic statistically associated with numerous moderate/high concerns. Survivors who identified white, were more likely than other people of other races to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding bodily changes after cancer (OR, 0.46), weight change (OR, 0.46), finances (OR, 0.46), debt (OR, 0.40), managing stress (OR, 0.55), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49). The odds of having a moderate/high concern regarding debt was 2.25 times higher given widowed marital status compared with those survivors who were single. Unemployment status, when compared with full-time employment, was significantly associated with increased odds of having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 2.08), bodily changes after cancer (OR, 1.72), memory and concentration (OR, 2.45), weight changes (OR, 2.17), finances (OR, 1.93), developing a new cancer (OR, 1.91), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.80).

As expected, respondents who had completed treatment were less likely to have many of the moderate/high concerns as those still undergoing treatment. Survivors who were up to 2 years posttreatment were significantly more likely than those survivors receiving treatment to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding fatigue (OR, 0.56), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.54), weight change (OR, 0.55), fears of the cancer returning (OR, 0.48), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.35), managing stress (OR, 0.43), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49).

However, those improved odds were not sustained over the cancer trajectory. Compared with survivors who were receiving treatment, survivors who were between 2-5 years posttreatment did not have significantly reduced odds for moderate/high concerns related to fatigue, sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress, and managing difficult emotions. They did have significantly reduced odds for having concerns only related to finances (OR, 0.61) and debt (OR, 0.52).

Long-term survivors, who were beyond 5 years posttreatment, had significantly reduced odds for having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 0.45), finances (OR, 0.52), debt (OR, 0.47), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.54), compared with survivors receiving treatment. Moderate/high concerns related to sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress did not have improved odds for these long-term survivors.