Demystifying the diagnosis and classification of lymphoma: a guide to the hematopathologist’s galaxy

JCSO 2017;15(1):43-48. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications. doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0328.

Histomorphologic evaluation

Despite the plethora of new and increasingly sophisticated tools, histologic and morphologic analysis still remains the cornerstone of diagnosis in hematopathology. However, for the characterization of an increasing number of reactive and neoplastic lymphoid processes, hematopathologists may also require immunophenotypic, molecular, and cytogenetic tests for an accurate diagnosis. Upon review of the clinical information, a microscopic evaluation of the tissue submitted for processing by the histology laboratory will be performed. The results of concurrent flow cytometric evaluation (performed on fresh unfixed material) should also be available in most if not all cases before the H&E-stained slides are available for review. Upon receipt of H&E-stained slides, the hematopathologist will evaluate the quality of the submitted specimen, since many diagnostic difficulties stem from suboptimal techniques related to the biopsy procedure, fixation, processing, cutting, or staining (Figure 1). If deemed suitable for accurate diagnosis, a search for signs of preservation or disruption of the organ that was biopsied will follow. The identification of certain morphologic patterns aids the hematopathologist in answering the first question: “what organ is this and is this consistent with what is indicated on the requisition?” This is usually immediately followed by “is this sufficient and adequate material for a diagnosis?” and “is there any normal architecture?” If the architecture is not normal, “is this alteration due to a reactive or a neoplastic process?” If neoplastic, “is it lymphoma or a non-hematolymphoid neoplasm?”

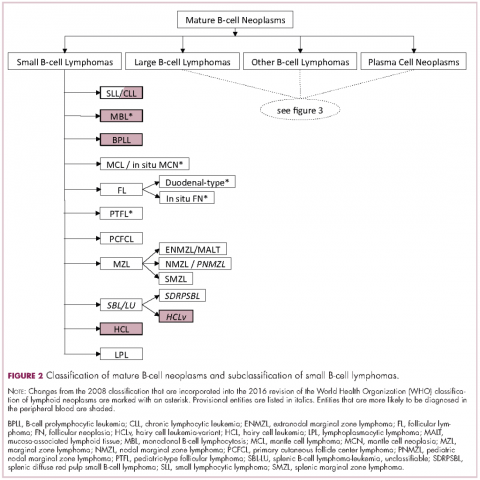

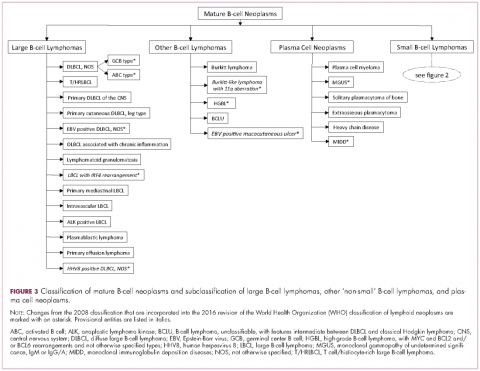

Both reactive and neoplastic processes have variably unique morphologic features that if properly recognized, guide the subsequent testing. However, some reactive and neoplastic processes can present with overlapping features, and even after extensive immunophenotypic evaluation and the performance of ancillary studies, it may not be possible to conclusively determine its nature. If the lymph node architecture is altered or effaced, the predominant pattern of infiltration (eg, nodular, diffuse, interfollicular, intrasinusoidal) and the degree of alteration of the normal architecture is evaluated, usually at low magnification. When the presence of an infiltrate is recognized, its components must be characterized. If the infiltrate is composed of a homogeneous expansion of lymphoid cells that disrupts or replaces the normal lymphoid architecture, a lymphoma will be suspected or diagnosed. The pattern of distribution of the cells along with their individual morphologic characteristics (ie, size, nuclear shape, chromatin configuration, nucleoli, amount and hue of cytoplasm) are key factors for the diagnosis and classification of the lymphoma that will guide subsequent testing. The immunophenotypic analysis (by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry or a combination of both) may confirm the reactive or neoplastic nature of the process, and its subclassification. B-cell lymphomas, in particular have variable and distinctive histologic features: as a diffuse infiltrate of large mature lymphoid cells (eg, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), an expansion of immature lymphoid cells (lymphoblastic lymphoma), and a nodular infiltrate of small, intermediate and/or mature large B cells (eg, follicular lymphoma).

Mature T-cell lymphomas may display similar histologic, features but they can be quite heterogeneous with an infiltrate composed of one predominant cell type or a mixture of small, medium-sized, and large atypical lymphoid cells (on occasion with abundant clear cytoplasm) and a variable number of eosinophils, plasma cells, macrophages (including granulomas), and B cells. HLs most commonly efface the lymph node architecture with a nodular or diffuse infiltrate variably composed of reactive lymphocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells and usually a minority of large neoplastic cells (Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells and/or lymphocyte predominant cells).

Once the H&E-stained slides are evaluated and a diagnosis of lymphoma is suspected or established, the hematopathologist will attempt to determine whether it has mature or immature features, and whether low- or high-grade morphologic characteristics are present. The maturity of lymphoid cells is generally determined by the nature of the chromatin, which if “fine” and homogeneous (with or without a conspicuous nucleolus) will usually, but not always, be considered immature, whereas clumped, vesicular or hyperchromatic chromatin is generally, but not always, associated with maturity. If the chromatin displays immature features, the differential diagnosis will mainly include B- and T-lymphoblastic lymphomas, but also blastoid variants of mature neoplasm such as mantle cell lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma, as well as high-grade B-cell lymphomas. Features associated with low-grade lymphomas (eg, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) include small cell morphology, mature chromatin, absence of a significant number of mitoses or apoptotic cells, and a low proliferation index as shown by immunohistochemistry for Ki67. High-grade lymphomas, such as lymphoblastic lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, or certain large B-cell lymphomas tend to show opposite features, and some of the mature entities are frequently associated with MYC rearrangements. Of note, immature lymphomas tend to be clinically high grade, but not all clinically high-grade lymphomas are immature. Conversely, the majority of low-grade lymphomas are usually mature.