Experiencing Age-Related Vision and Hearing Impairment: The Psychosocial Dimension

From the University of Education (Dr. Heyl) and Heidelberg University (Dr. Wahl), Heidelberg, Germany.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the current state of research regarding the experience of age-related vision and hearing impairment.

- Methods:Review of the literature.

- Results: Negative consequences of age-related vision and hearing impairment manifest in the domains of health and longevity, everyday competence, cognitive functioning, social functioning, and subjective well-being. However, while vision impairment strongly impacts everyday competence, the burden of hearing impairment can mainly be found in the social domain. Psychosocially framed intervention research has shown promising findings, but many studies rely on small samples or do not include a control condition.

- Conclusions: Although more research is needed, it is clear that traditional rehabilitation programs targeting age-related vision and hearing impairments need a strong psychosocial component.

Vision and hearing are essential for person–environment interaction and both are subject to pronounced age-related changes. Ongoing demographic changes and increasing life expectancy is contributing to a significant increase in the number of very old individuals [1]. It is projected that by 2030 about 50% of older Americans may have some significant eye disease, ie, cataract, glaucoma, or age-related macular degeneration [2]. Presbycusis as the major cause of age-related hearing impairment is present in 40% of the American senior citizens [3]. In this narrative review, we review the epidemiological data on age-related vision and hearing impairment, research on its psychosocial impact, and intervention research aimed to improve coping processes and rehabilitative outcomes. We close with future recommendations directed both toward research and clinical practice.

Epidemiology

Vision and hearing impairment is highly prevalent in old age, yet prevalence rates reported in the literature are quite different, depending on the definition of vision and hearing impairment used. A widely used criterion for low vision is the one used by the World Health Organization, ie, visual acuity less than 20/60 and equal to or better than 20/400 in the better eye with best correction. A best corrected visual acuity of less than 20/400 in the better eye is used to define blindness [4]. A disabling hearing impairment is defined by an average hearing loss in decibel (dB HL) of at least 41 dB HL at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. [5]. Translated to everyday life, such hearing impairment mainly manifests in severe difficulties in understanding normal conversation. Besides differing definitions, different methods to assess vision and hearing impairment and heterogenous study populations make comparisons of prevalence rates difficult [6]. In particular, relying solely on self-report data to assess vision and hearing loss seems generally problematic. In addition, the strong focus in vision impairment assessment on visual acuity measures has limitations, as other indicators, such as contrast sensitivity or useful field of vision, may be more important for out-of-home mobility or driving [7].

A recent study on the prevalence of visual impairment (defined as best corrected visual acuity < 20⁄40) in 6 European countries found quite similar prevalence rates as reported for the US: Prevalence of visual impairment was 3% in those aged 65 to 74 years, 13% in those over 75 years and 33% in those over 85 years [8]. At first glance, vision loss seems to be more prevalent among older women than among older men, but this relationship is not sustained in multivariate analyses considering age, health, and social support variables [9].

Regarding hearing loss, Gopinath et al [10] found prevalence rates of 29% among men and 17% among women aged 60 to 69 years. Moreover, for every 10 years of age, the prevalence of hearing loss doubled. In their review of epidemiologic data on prevalence of age-related hearing impairment in Europe, Roth and coauthors [11] report that at the age of 70 years, about 30% of men and 20% of women were found to have a hearing loss of at least 30 dB HL, while at the age of 80 years about 55% of men and 45% of women were affected. Lin et al found that 63% of those 70 years and older had a hearing loss of more than 25 dB in the better ear [12].

According to a recent review by Schneider et al [6], prevalence of impairment in both vision and hearing in older age (dual sensory impairment) varies between 1.6% and 22.5% due to different sample characteristics (eg, size, age) and different definitions and assessments of vision and hearing impairment (see also [13]). However, there is good evidence that dual sensory impairment increases with age, and that it is more common among frailer subpopulations such as older individuals consulting care services [6].

Quality of Life Impact of Vision and Hearing Impairment

Health and Longevity

There is inconsistent evidence that both age-related vision and hearing impairment are accompanied by heightened multimorbidity and an increased mortality rate. For example, while some older as well as more recent studies have found that visual and hearing declines over time predict death in very old age [14–16], other studies have detected no significant relationship after adjusting for confounders such as age, gender, and education [17,18]. Among the hearing impaired, only men seem to have a significant increase in mortality risk [15,19]. Dual sensory impairment appears to be more consistently and more strongly related to increased mortality than vision or hearing impairment alone [19–21].

Everyday Competence

The term everyday competence includes both basic (eg, self-care behaviors) and instrumental (eg, using public transport) activities of daily living (ADL/IADL [22]). Age-related vision impairment has been found to be robustly associated with significantly lower everyday competence, because visual capacity is a critical prerequisite for such behaviors [23,24]. Indeed, lowered everyday competence appeared as the best of a range of variables (including cognitive function and well-being–related measures) used to differentiate between visually impaired and visually unimpaired older adults [18]. Furthermore, vision impairment impacts cross-sectionally as well as longitudinally—more strongly on IADL as compared to ADL—because the execution of IADL is more complex and depends more strongly on environmental enhancing or hindering factors [25–27]. Hence, shrinkage in IADL competence reflects a kind of early behavioral marker of severe vision impairment, whereas significant ADL decrease only happens later in the process of chronic vision loss.

In contrast to vision impairment, age-related hearing loss has been found not to have a major impact in particular on ADL/IADL [28]. However, as has been found elsewhere [29], hearing loss is associated with increased reliance on community and informal supports, suggesting that while IADL function may not deteriorate with hearing loss, the way it is conducted may change (ie, need for support to maintain participation).

It should also be mentioned in this context that assessment strategies have been developed to better consider the specific life conditions of those with vision and hearing impairment. The best-known and frequently applied instruments in this context are the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire [30] and the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly [31].

Cognitive Functioning

Previous research largely supports the notion that reduced vision and hearing function is accompanied by a decrease in cognitive performance in older adults. The work of Lindenberger and Baltes, based on the Berlin Aging Study (BASE)—but also including additional studies with a wider age-range—is central in supporting a strong connection among vision, hearing, balance, and cognitive functioning in later life. Lindenberger and Baltes [32] found that general intelligence correlated just as strongly with visual as with auditory ability. In a model conjoining age, sensory function, as well as intelligence, visual and auditory function predicted a large portion of interindividual differences in intelligence and indeed fully mediated the negative correlation between age and intelligence. This finding has meanwhile been replicated by a number of other research groups and may be regarded as rather robust [33,34]. In addition, Baltes and Lindenberger [35] observed that sensory measures were better predictors of intelligence than socio-structural variables such as education or social class. They also showed that the connection among sensory functioning and intelligence was much closer in older adults as compared to adults in early and middle adulthood [34].

No clear difference between the sensory modalities of vision and hearing has been identified regarding their relationship with cognitive performance. On the one hand, there is research supporting the view that both vision and hearing impairment are connected with cognitive decline [12,36,37], while some evidence also supports that the linkage may be stronger with vision [14]. On the other hand, there are also data not supporting a close connection between vision and hearing impairment and cognitive function [38]. Explanations for such inconsistencies may refer to a number of reasons, such as pronounced positive selectivity of samples (which may lead to underestimation of connections among sensory and cognitive function), the application of established cognitive tests not appropriate for sensory impaired older adults (which may lead to overestimation of connections among sensory and cognitive function), and the application of different cut-off scores for significant vision and hearing impairment (possibly, higher cut-offs may lead to higher, lower to lower connections). Longitudinal data using the latest in causal modeling data analysis support the view that the causal dynamics involved in sensory and intelligence change are complex and that each of these variables can drive change in the other across longer periods of later life [39].

Vision status also plays a role when it comes to the connection between cognitive function and everyday competence—a linkage that is generally challenged as people age and that may lead to endpoints such as dependence on others and transition to long-term care. Heyl et al [40] observed that the link between vision status and out-of-home leisure activities is mediated by cognitive status. In a more recent study, able to add to the understanding of such a mediation process, Heyl and Wahl [38,41] showed that the connection between cognitive function and everyday function is much closer in visually and hearing impaired older adults as compared with visually unimpaired older adults, which possibly means that both visually and hearing impaired elders rely more intensely on their cognitive resources. Causality dynamics may however also work in the opposite direction. As Rovner and colleagues [42,43] observed in a study with age-related macular degeneration patients over 64 years of age covering a 3-year observation period and 2 measurement occasions, activity loss over time due to the visual loss led to cognitive decline happening between T1 and T2. This finding fits well with the more general finding in the cognitive aging literature that the exertion of social and leisure activities is important for maintaining cognitive functioning [44].

Social Functioning

Social relations as well as social support have generally been found to be of key importance for older adults [45]. Reinhardt [46] found that visually impaired older adults nominated on average 5.4 persons of intimate relation within their family network, and 3.5 persons within their friendship network, which is similar to sensory-unimpaired older adults, such as those assessed in the BASE [47]. In addition, in Wahl et al’s study [18], visually and hearing impaired older adults nominated practically the same number of persons as being in the most intimate circle of their social network (4.70 versus 4.71); the respective number in a comparison group of visually unimpaired older adults amounted to 5.2 persons, which was not significantly different from both sensory impaired group means.

Neither vision nor hearing impairment seem to affect the experience of loneliness dramatically [18,23,48], although some research did report an increased risk of loneliness in older adults with vision impairment [49]. It is clear however that hearing impairment more strongly than vision impairment negatively impacts social communication and carries a strong stigma for those affected [48,50]. The stigma particularly implies that hearing deficits and concomitant communication disturbances (eg, giving an answer that does not match the question) elicits the view of a cognitively impaired, if not demented older person. In some contrast, vision loss seems to raise rather strong helping impulses and feelings of compassion. The dark side of this tendency is that it seems a challenge to provide visually impaired older adults with the instrumental support needed while at the same time fostering remaining capabilities [51]. Overprotection may put constraints on the visually impaired older adults’ “true” functional capacity and thereby contribute to loss in competence over the longer run due to disuse [52].

Subjective Well Being–related Outcomes and Depression

Visually impaired older adults have shown evidence of diminished well-being as compared with sensory unimpaired older adults [53], although effect sizes were rather small in a respective meta-analysis [54]. Differences in well-being between hearing impaired and unimpaired older adults seem small or nonexistent in some studies [18,55], but considerable in others [56]. The latter study covering a 16-year observational period as well as other longitudinal work (eg, [57]) also support the notion that remaining ADLs and social engagement mediate the linkage between sensory loss and well-being and depression. The “well-being paradox” in old age, pointing to pronounced adaptive resources to maintain well-being in spite of adverse conditions [58], may also apply to sensory impaired older adults [57,59].

At the same time, it is critical to acknowledge that visually impaired older adults represent an at-risk population, in which the positive impact of human adaptation and the drawback of reaching the limits of psychological resilience go hand in hand. Affect balance (ratio of positive and negative affect) has been found to be more toward the negative pole in visually impaired older adults [60] and depression has consistently been found to be significantly increased in visually impaired older adults [61–63]. Rates roughly vary between 15% and 30% and are particularly high in age-related macular degeneration patients [61]. This is also important, because depressive symptoms may accelerate both cognitive decline and decline in everyday competence in age-related macular degeneration patients [42]. Perceived overprotection may also lead to negative consequences in terms of heightened depression and anxiety over time [64].

Regarding the impact of hearing loss on depression, findings are quite inconsistent. Some studies found evidence for a significant relationship between hearing impairment and depressive symptoms among older adults [65, 66], while others did not [67, 68]. Gopinath and co-workers [66] observed that hearing impaired individuals, particularly women, younger than 70 years of age and those who were infrequently using a hearing aid (less than one hour per day) were more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms. According to a population-based study among older Italians, hearing impairment might be more closely related to anxiety symptoms than to depression [69].

Dual Sensory Impairment

Previous research supports the notion that the overall psychosocial situation of those with dual sensory impairment is even worse as compared to those with sole vision or hearing impairment. In particular, higher rates of ADL/IADL impairment, depression and lowered well-being have been found in older adults affected by dual sensory loss [6,13,18,56]. Also, dual sensory impairment has been found to be linked with cognitive decline cross-sectionally [37] as well as longitudinally [36].

Improving Quality of Life in Sensory Impaired Older Adults

The research summary provided in the previous section underscores that the experience of age-related visual and hearing impairment comes with pronounced challenges that deserve evidence-based professional support. In the following, we give an overview and evaluation of major work in the area of psychosocially framed intervention research targeting older adults with vision and hearing loss. By psychosocially framed interventions we mean studies containing programs that focused on psychosocial processes (eg, consultation on how to better cope with sensory impairment, educative components, problem solving strategies, coping with negative affect) and assessed psychosocial outcomes (eg, everyday functioning, depression, emotional stress experiences). Such interventions may have been integrated into regular rehabilitation programs or offered as a separate strategy in addition to classic rehabilitation. We also consider physical activity–related and overall “way of living” interventions such as tai chi and yoga. In doing so, our aim is to highlight the bandwidth of psychosocial interventions and respective outcomes, not comprehensiveness.

Age-related Vision Impairment

Most psychosocially framed interventions could be characterized as self-management– and disease management–like efforts and are promising for visually impaired older adults. Major elements of such programs include stress-reducing strategies (eg, muscle-relaxation exercises), goal-directed problem-solving, strategies to evoke positive affect, activating available resources, and information and consultation. Typically, such programs are conducted in a group format in an eye clinic, bringing together 6 to 8 visually impaired older adults for weekly sessions of 2 to 3 hours over 6 to 8 weeks.

More recent work provides additional support for the usefulness of self-management programs for visually impaired older adults [72,73]. In addition, emerging evidence supports the notion that psychosocially framed interventions may contribute to saving health costs (eg, via reduced psychopharmacy) and may also enhance commitment

It is also obvious that such programs should find a strong liaison with classic high-caliber rehabilitation programs for visually impaired older adults, including effective reading training [75].

Furthermore, physical training programs, which have proven efficiency with old and very old individuals—including those who are cognitively vulnerable—also seem to be of significant advantage for visually impaired older adults. As has been found, such programs not only increase posture, gait, and general physical fitness, they also prevent falls and enhance well-being, self-efficacy, and cognitive function, especially executive control [76]. Postural control has been improved by multimodal balance and strength exercises among older individuals with visual impairments as well [77]. Participation in physical activity and being in better physical condition buffered the relationship between dual sensory impairment and depression, pointing to the importance of physical training programs for the mental health of older persons with dual sensory impairment [78]. According to a randomized control study as well as to some case studies, tai chi seems to be an effective tool to improve balance control in visually impaired older adults, and thus to reduce an important risk factor for falls [79–81]. Visually impaired adults might also benefit from yoga in terms of balance improvement as well as psychosocial improvements [82]. To teach tai chi efficiently, it is necessary to adapt instructions to the needs of the visually impaired seniors by relying on verbal cuing and manual body placement [80]. The need to adapt instructions and to provide an accessible environment (including transportation arrangements) to motivate older individuals with visual impairments to perform regular physical exercises is also highlighted by Surakka and Kivela [83].

Furthermore, there is evidence that state of the art low vision rehabilitation as such also has beneficial effects on psychosocial outcomes, such as general and vision-related quality of life and emotional well-being.

Age-related Hearing Impairment

Interventions concerning older adults with hearing impairment center on amplification and aural rehabilitation, including auditory training [84]. It has been shown that using hearing aids improves the quality of life, in particular hearing-related quality of life, of hearing impaired adults [85]. Yet many older adults who would benefit from hearing aids do not wear them [86]. From the reasons identified in the review by McCormack and Fortnum [86], perceived hearing aid value, in particular poor benefit in noisy situations, fit and comfort, as well as care and maintenance of the hearing aid emerged as most important. Improvements in these areas are necessary to enhance hearing aid usage among older adults with hearing impairment. Meyer and Hickson [87] identified 5 factors increasing the likelihood to seek help for hearing impairment and/or adopt hearing aids: (1) moderate to severe hearing impairment and perceived hearing-related everyday limitations; (2) older age; (3) poor subjective hearing; (4) perceiving more benefits than barriers to amplification; and (5) perceiving significant others as supportive of hearing rehabilitation. Thus, the involvement of family members in the rehabilitation process appears necessary and promising.

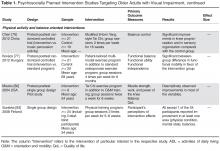

Beyond amplification, aural rehabilitation seeks to improve the situation of hearing impaired older adults by providing listening and communication techniques to enhance communication effectiveness. We have summarized major work in this area in Table 2.

In sum, it seems clear for both vision impairment [95] and hearing impairment [96] that classic rehabilitation strategies, such as fitting a reading device or hearing aid, need significant enrichment by psychosocial training components in order to achieve the best outcomes possible. Furthermore, given the findings on the role of cognitive resources in visually impaired older adults (see respective section above), cognitive training may be an important addition to psychosocial intervention and rehabilitation [38,97]. It must be noted, however, that many of the available studies reveal a number of methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, missing control condition, and no follow-up assessments to estimate the maintenance of effects.

A significant future need is intervention research addressing older adults with dual sensory impairment. Although we found study protocols related to important trials underway [98,99] and a physical training study with visually impaired older adults that included also some dual sensory impaired individuals [83], it seems that there is not much research in terms of completed interventions and respective findings. Furthermore, it may be important to better involve significant others such as family members and friends in psychosocially framed programs and emerging research with low vision adults has revealed advantages and disadvantages of such an approach [100].

Practical Implications

The older patient is on the way to become the “standard” patient for eye care and hearing specialists and thus a challenge for public health at large. Based on the evidence compiled above, we argue that best practice in medical treatment and traditional rehabilitation of vision and hearing impairment should better consider the psychosocial dimension of age-related vision and hearing impairment. We see different levels at which a stronger psychosocially framed input is needed. First, at the diagnostic level, having a better understanding of everyday competence, the role of cognitive functioning, social resources, and well-being–related dynamics in visually impaired and hearing impaired older adults may significantly enrich the professional background knowledge about the patient. Such knowledge may become important for diagnostic evaluation, treatment decisions, and predictions of long-term outcomes. It seems also critical to have an understanding of the more fundamental mechanisms and systemic inter-relations in older patients (eg, among visual, hearing, mobility, and cognitive impairment), because such evidence helps to evaluate overall vulnerability and likely future trajectories of respective patients.

Second, at the intervention level against the background of the available empirical effectiveness evidence, self-management–oriented and psycho-educative programs should become a regular component of low vision rehabilitation. Similarly, psychosocial programs educating older adults in hearing tactics and hearing loss–oriented coping strategies should become a regular part of hearing rehabilitation. In addition, we argue that cognitive training and physical activity–oriented interventions should have their place in rehabilitation programs designed for older visually and hearing impaired adults. The major reason is that respective programs generally have been found to positively impact quality of life in old age. This impact may be particularly valuable for more vulnerable populations, such as sensory impaired older adults. We therefore recommend implementing psychosocially framed programs as a regular service in eye clinics as well as in ear, nose, and throat clinics, because this seems to be the setting best suited to approach visually and hearing impaired older adults as well as to offer the logistic opportunities to conduct such programs. It would also be critical to extend such programs to in-home services as well as services covering long-term care settings. Older adults with dual sensory impairment bring specific challenges to such interventions, such as the optimal cooperation and combination of rehabilitation and psychosocial expertise related to each domain and traditionally offered side by side. It is also good news that new trials are underway to learn more about psychosocial interventions aimed to address older adults with dual sensory loss [98,99].

In conclusion, we argue for a better implementation of both age-related psycho-ophthalmology as well as psycho-audiology. Although we regard psychologists with a clinical training background as a key profession to be involved in psychosocially framed interventions with older adults with vision and hearing impairment, other professions (eg, occupational therapists, sport scientists) should also play an important role. A multiprofessional enrichment of classic sensory rehabilitation based on the training principles as described above is a major future need.

Corresponding author: Vera Heyl, PhD, Zeppelinstr, 1, D-69121, Heidelberg, Germany, heyl@ph-heidelberg.de.

Financial disclosures: None.