Current Management and Future Directions in the Treatment of Gallbladder Cancer

Clinical outcomes of patients with gallbladder cancer have improved considerably with the advent of immunotherapy and targeted therapies. While specialists have gained tremendous insights into the disease over the last 10 years, significant knowledge gaps remain, as relapse rates remain high. Early referral to specialized treatment centers and timely molecular profiling can help guide therapeutic regimen choice and potentially improve patient outcomes.

Insights Into Disease Prevalence and Development

Gallbladder cancer is a rare malignancy with an aggressive course. Most gallbladder cancers are of epithelial origin, with adenocarcinoma being the most common type.1 Approximately 12,350 new cases of gallbladder cancer and nearby large bile duct cancers are anticipated in 2024 in the United States,2 predominantly affecting Southwestern Native Americans.3 The prevalence of gallbladder cancer varies greatly worldwide; rates are highest in South America (mainly in Chile) and Southeast Asia, including Eastern India.3,4

Multiple factors, including environment and genetics, contribute to the development of gallbladder cancer, which is driven primarily by chronic inflammation.5 While there are no defined risk factors, this malignancy is mostly associated with female sex, chronic gallbladder infections, and gallstones.4 Some evidence also suggests a dietary association with consuming mustard seed oil.6 Exposure to certain environmental toxins or heavy metals may also contribute to disease risk.1,4

,Several genetic alterations have been identified in patients with gallbladder cancer that may be related to disease etiology; these include somatic mutations in the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), and tumor protein p53 (TP53) genes, and many others.7,8 In addition to somatic mutations, gene overexpression, epigenetic changes, and microRNA-associated changes have also been linked to the disease.3

Challenges in Uncovering a “Hidden” Disease

While most gallbladder cancers are usually detected incidentally, patients may present with symptoms of abdominal pain, discomfort, and biliary obstruction–related symptoms like jaundice, itching, and dark urine.3,9,10 Cases may initially be misdiagnosed as inflammatory conditions such as cholecystitis or gallbladder stones; as a result, patients may be rushed into an inappropriate or incorrect surgical intervention.11 For these reasons, as well as the tight anatomical location of the gallbladder, cases are often not detected until advanced-stage disease.3,4

Patients diagnosed in stage 4 with distant metastases have an expected survival rate of less than 1 year,12 and low referral rates are associated with poor outcomes.13 Patients with suspected disease should therefore be referred to a specialized treatment center as soon as possible to confirm a diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment. Core biopsies can provide histological confirmation, where feasible and safe, followed by imaging to determine extent of the disease.14

Evolving Management of Localized and Advanced Disease

Localized disease

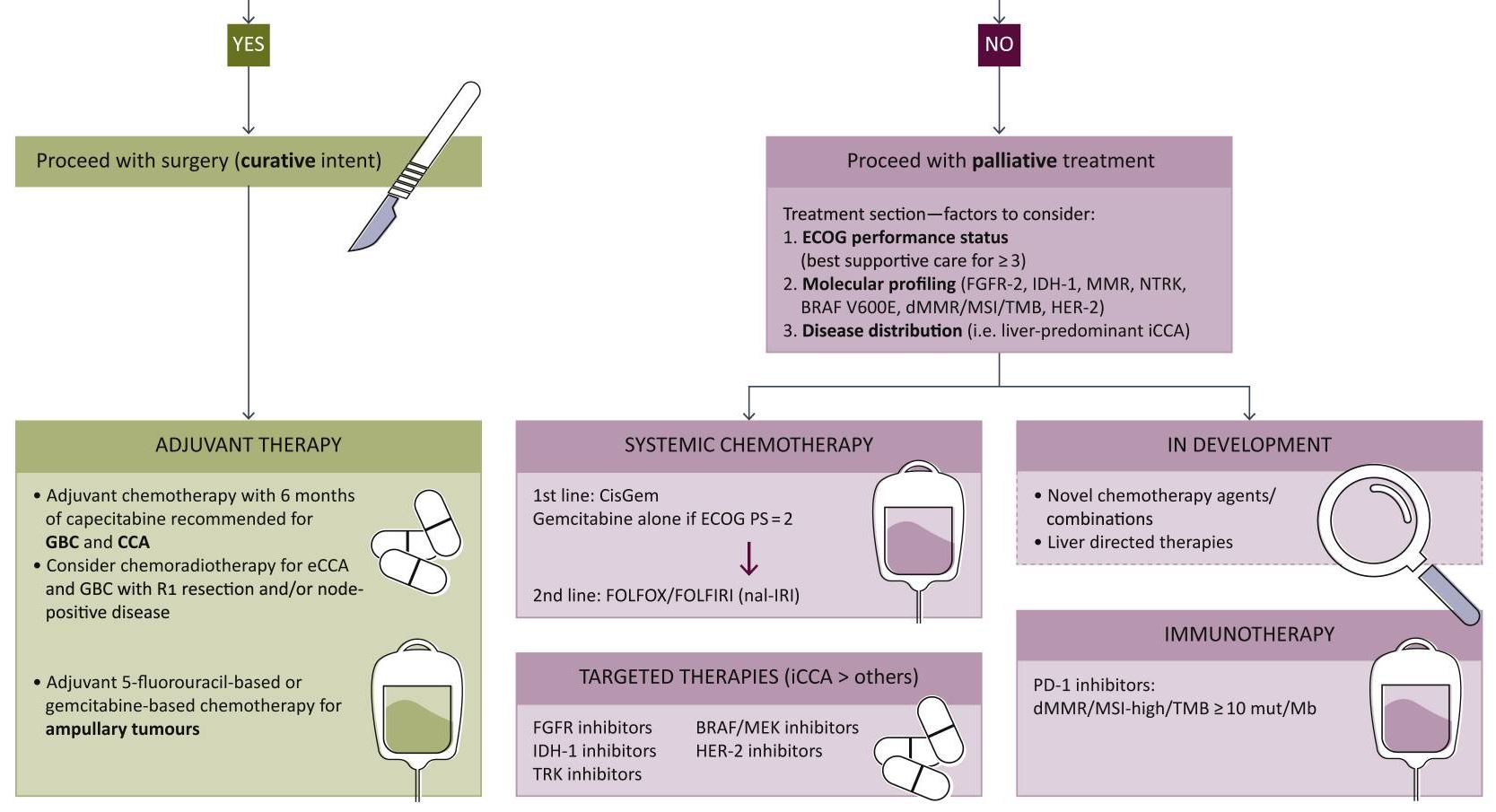

Surgery with curative intent is the standard of care in patients with localized disease (Figure).14,15 Contraindications for resection include distant metastases and occlusion of blood vessels.4 Depending on tumor stage, eligible patients may undergo radical cholecystectomy and portal lymphadenectomy, as well as potential liver resection (segments 4b and 5).5

Figure. Biliary Tract Cancers (BTCs): Diagnosis and Management Algorithm14

From Lamarca A, Edeline J, Goyal L. How I treat biliary tract cancer. ESMO Open. 2022;7(1):100378. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100378. [Open access].

As the nonencapsulated nature of the gallbladder renders local extension very likely, a peri-adjuvant approach including neoadjuvant and adjuvant arms should be initiated. Standard chemotherapy regimens may include capecitabine or gemcitabine + cisplatin/capecitabine.16,17

Advanced disease

Systemic therapy remains key in the setting of locally advanced or metastatic disease. In August 2024, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated its guidelines to strongly recommend durvalumab + gemcitabine + cisplatin or pembrolizumab + gemcitabine + cisplatin as the preferred regimens for primary treatment of these patients.17 Other regimens to consider based on both NCCN and European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines include gemcitabine + cisplatin or capecitabine + oxaliplatin.17,18 In addition, gemcitabine + S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil) may also be considered as part of first-line treatment based on data from clinical trials conducted in Japan.19 FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin) is recommended for second-line treatment.16

While the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines are yet to be published, they have previously reviewed data on several potential novel agents and targeted therapies for first-line treatment.20

The addition of immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors to the treatment algorithm has been monumental for the treatment of advanced gallbladder cancer. Durvalumab and pembrolizumab, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PDL-1) receptor inhibitors, in combination with gemcitabine + cisplatin, significantly improve overall survival compared to gemcitabine + cisplatin alone.17,21,22 These regimens are strongly recommended as first-line therapy in eligible patients who have not previously been treated with a checkpoint inhibitor.

Biopsies should be performed as early as possible in all patients with unresectable or metastatic disease for genomic profiling. Next-generation sequencing can help inform response to targeted therapies in testing by identifying genetic mutations, potentially improving treatment response.1,23

In certain circumstances, patients with genetic mutations are eligible for molecularly targeted therapies17:

Unresectable or metastatic disease:

- Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusion-positive tumors: entrectinib, larotrectinib, or repotrectinib

- High mutational burden (TMB-H) tumors: nivolumab + ipilimumab

Following disease progression:

- B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase (BRAF) V600E-mutated tumors: dabrafenib + trametinib

- Cholangiocarcinoma with fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) fusions: futibatinib + pemigatinib

- Cholangiocarcinoma with rearrangements or isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations: ivosidenib

It is important to note that further development of adjuvant strategies is greatly needed to better guide management across disease stages.16

Therapeutic candidates in testing

Despite the advancements achieved with immunotherapies and targeted treatments, therapeutic options have remained comparable to those of other biliary tumors such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. However, some novel candidates currently being evaluated in clinical trials have shown promise24-26:

HER2: Overexpression of the HER2 protein in gallbladder cancer causes abnormal cell survival and proliferation. Initial clinical trial data have suggested that agents targeting HER2 may improve outcomes in patients with advanced gallbladder cancer who harbor somatic HER2 mutations. In fact, the anti-HER2 agent zanidatamab provided clinical benefit and was well tolerated in patients with treatment-refractory, HER2-positive biliary tract cancer in a phase 2 single-arm trial.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): The VEGF/ VEGF receptor pathway may also be a promising target due to its role in regulating epithelial cell differentiation and migration. Phase 2 studies of VEGF antibodies, such as bevacizumab, in combination with standard chemotherapy have demonstrated improved response rates; however, some of these studies have shown mixed results.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): This key signaling pathway plays an important role in driving cancer growth and metastases. Early trials of an mTOR inhibitor in combination with standard chemotherapy have demonstrated an acceptable tolerability profile with potential signs of clinical benefit.

The immunotherapy landscape for gallbladder cancer may evolve beyond currently approved PD-1/PDL-1 receptor inhibitors with the development of agonist antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) candidates.27 Novel treatment approaches like vaccines and nanoparticle delivery systems are also under investigation.

Looking Toward the Future

Gallbladder cancer is challenging to detect, and earlier diagnosis is key to improving outcomes. It is critical to refer patients to specialized treatment centers as soon as the disease is suspected. Rapid development in advanced genetic testing and other analytical methods may lead to identification of diagnostic biomarkers to aid in detecting cases sooner.24

Despite the fast-evolving pipeline for therapeutic candidates, greater research is also needed to inform sequencing of chemotherapy regimens with immunotherapy and targeted therapy to achieve favorable long-term outcomes.27 As new candidates are approved, management may become remain less than ideal without this crucial guidance.

We hope the future will bring the opportunity to provide more tailored treatments to patients with novel candidates that can further engage the immune system beyond currently identified targets.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.