New concepts in the management of acute pancreatitis

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a 2.9-fold higher risk for AP versus non-IBD cohorts26 with the most common etiologies are from gallstones and medications.27 In patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the risk of AP is higher in those who receive peritoneal dialysis, compared with hemodialysis28-33 and who are women, older, or have cholelithiasis or liver disease.34As recently reviewed,35 pancreatic cancer appears to be associated with first-attack pancreatitis with few exceptions.36 In this setting, the overall incidence of pancreatic cancer is low (1.5%). The risk is greatest within the first year of the attack of AP, negligible below age 40 years but steadily rising through the fifth to eighth decades.37 Pancreatic cancer screening is a conditional recommendation of the ACG guidelines in patients with unexplained AP, particularly those aged 40 years or older.1

Etiology and diagnosis

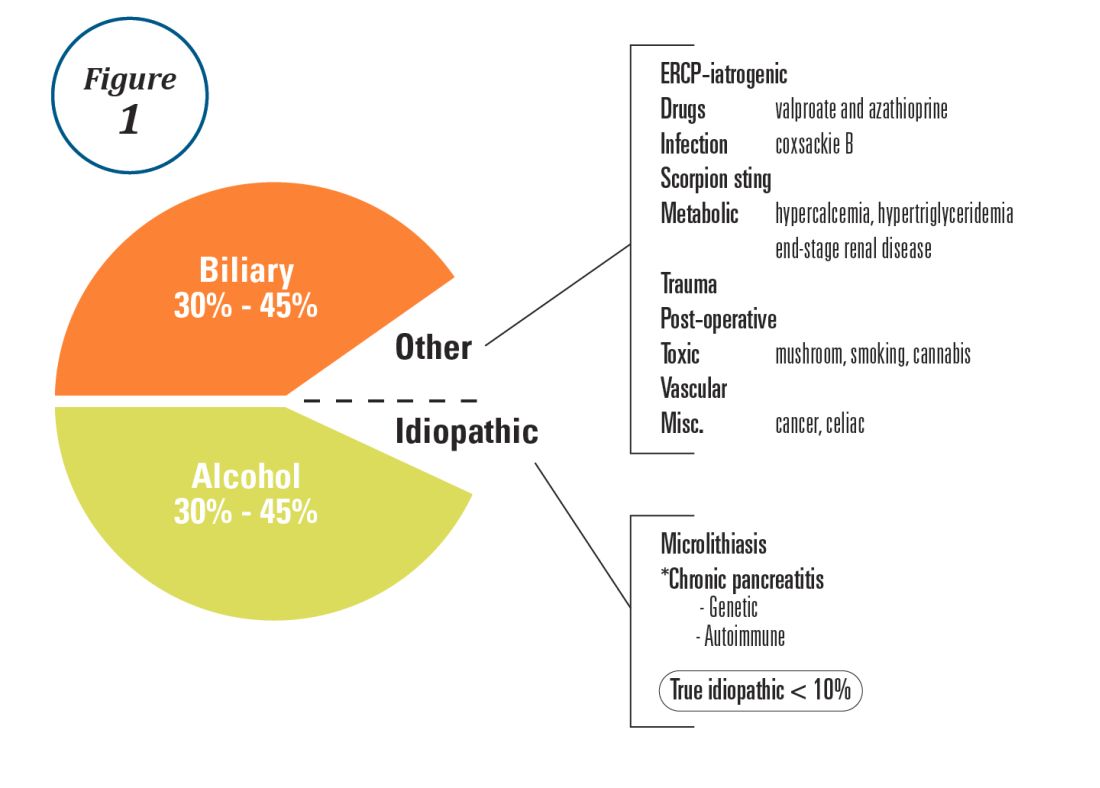

Alcohol and gallstones remain the most prevalent etiologies for AP.1 While hypertriglyceridemia accounted for 9% of AP in a systematic review of acute pancreatitis in 15 different countries,38 it is the second most common cause of acute pancreatitis in Asia (especially China).39 Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the etiologies and risk factors of pancreatitis. Importantly, it remains challenging to assign several toxic-metabolic etiologies as either a cause or risk factor for AP, particularly with regards to alcohol, smoking, and cannabis to name a few.

Guidelines and recent studies of AP raise questions about the threshold above which hypertriglyceridemia causes or poses as an important cofactor for AP. American and European societies define the threshold for triglycerides at 885-1,000 mg/dL.1,42,43 Pedersen et al. provide evidence of a graded risk of AP with hypertriglyceridemia: In multivariable analysis, adjusted hazard ratios for AP were much higher with nonfasting mild to moderately elevated plasma triglycerides (177-885 mg/dL), compared with normal values (below 89 mg/dL).44 Moreover, the risk of severe AP (developing POF) increases in proportion to triglyceride value, independent of the underlying cause of AP.45

Diagnosis of AP is derived from the revised Atlanta classification.46 The recommended timing and indications for offering cross-sectional imaging are after 48-72 hours in patients with no improvement to initial care.1 Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has better diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, compared with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for choledocholithiasis, and has comparable specificity.47,48 Among noninvasive imaging modalities, MRCP is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for diagnosing choledocholithiasis.49 Despite guideline recommendations for more selective use of pancreatic imaging in the early assessment of AP, utilization of early CT or MRCP imaging (within the first 24 hours of care) remained high during 2014-2015, compared with 2006-2007.50

ERCP is not recommended as a pure diagnostic tool, owing to the availability of other diagnostic tests and a complication rate of 5%-10% with risks involving PEP, cholangitis, perforation, and hemorrhage.51 A recent systematic review of EUS and ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis concluded that EUS had lower failure rates and had no complications, and the use of EUS avoided ERCP in 71.2% of cases.52