Abdominal Pain and Fever 48 Hours After Hysterosalpingography

Diagnostic Considerations

Clinically, patients with TOAs present with fever, chills, lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge with cervical motion tenderness, and an adnexal mass on examination.3 When a TOA is suspected, a urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and testing for C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae are warranted. An ED workup often reveals leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Imaging is recommended once a TOA is suspected. Ultrasound is the gold-standard imaging modality and boasts a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 98% for the detection of TOAs; however, CT has also been shown to be an effective diagnostic modality.4

Despite being common, TOAs are difficult to predict, detect, and diagnose; thus the clinician must often rely on thorough history taking and physical examination to raise suspicion.5 Although most frequently associated with sexual transmission, TOAs occur in not sexually active women in adolescence and adulthood. Specifically, TOAs also can present secondary to other intra-abdominal pathologies, such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, and pyelonephritis, as well as a complication of intrauterine procedures, such as an HSG, or less commonly, following intrauterine device (IUD) insertion.5-7

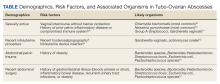

Given that sexually transmitted infections are the most common etiology of TOAs, C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae are the most likely microorganisms to be isolated (Table).8-12 In not sexually active populations, Escherichia coli and Gardnerella vaginalis should be considered instead. Although rare, women with IUDs have been shown to have an increased incidence of PID/TOA secondary to Actinomyces israleii relative to women without IUDs.12 In patients with TOAs secondary to intraabdominal surgery, anaerobic bacteria, such as Bacterioides and Peptostreptococcus species in addition to Escherichia coli, are likely culprits.11

In patients after HSG, infectious complications are uncommon enough that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against antibiotic prophylaxis unless there are risk factors of dilated fallopian tubes or a history of PID.13 Identifying a precise percentage of TOA as a complication of HSG is rather elusive in the literature, though, it is frequently noted that infection in general is uncommon, and the risk of developing PID is about 1.4% to 3.4%.14 However, in the retrospective study most often cited, all women who developed PID following HSG had evidence of dilated fallopian tubes. Given our patient had no history of PID or dilated fallopian tubes, her risk of developing infection (PID or postprocedural abscess) would be considered very low; therefore, the index of suspicion also was low.15

Following diagnosis, the patient was promptly admitted and treated with a course of IV ceftriaxone 1 g every 24 hours, IV doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours, and a single dose of IV metronidazole 500 mg. Her leukocytosis, fever, and pain improved within 48 hours without the need for percutaneous drainage and the patient made a complete recovery.