Pharmacist Interventions to Reduce Modifiable Bleeding Risk Factors Using HAS-BLED in Patients Taking Warfarin

Most of the interventions recommended evaluating the use of antiplatelet agents, particularly aspirin. The benefits of antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease are well established. However, for AF patients on OAC therapy, the concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy significantly increases the risk of bleeding and should be reserved for high-risk patients.10 The 2012 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines support the use of OAC monotherapy in patients with AF with stable CAD, including patients with a myocardial infarction or percutaneous coronary intervention more than 1 year previously, which has been corroborated with guideline and expert consensus recommendations released in 2016.7,8,10,11

For patients taking warfarin for AF without CAD, the possible benefit of concomitant aspirin therapy for primary prevention is outweighed by the increased risk of major bleeding.12 Furthermore, warfarin monotherapy has been shown to be effective in primary prevention of CAD and seems to have cardiovascular benefit for secondary prevention but with increased bleeding.13,14 As a result, through the exclusion criteria this project aimed to evaluate warfarin patients with AF at low risk of cardiovascular events who might be taking unnecessary concurrent antiplatelet therapy.

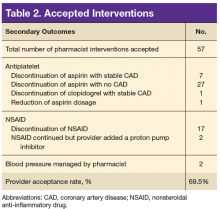

More than one-half of the interventions involved discontinuing antiplatelet therapy. Chart reviews revealed a lack of documentation for the indication and intended duration of antiplatelet therapy. In many patients, it is likely that aspirin use predated AF diagnosis and warfarin initiation. In some of these cases, it would have been appropriate to discontinue aspirin when starting warfarin use. Although there is guidance to support the use of OAC monotherapy in patients with AF with stable CAD, the patient’s provider and cardiologist made the decision to discontinue an antiplatelet agent after weighing benefits and risks. Regardless of the outcome, this analysis revealed the importance and need for routine review of antiplatelet therapy and documenting the rationale for antiplatelet use in addition to anticoagulation.

The second largest category of interventions accepted was for evaluation of NSAID use. A 2014 study by Lamberts and colleagues found that concomitant use of oral anticoagulants and NSAIDs conferred an independent risk for major bleeding and thromboembolism in patients with AF.15 The increase in serious bleeding (absolute risk difference of 2.5 events per 1,000 patients) was observed even with short-term NSAID exposure of 14 days across all NSAID types (selective COX-2 inhibitors or nonselective NSAIDs). In addition, there was an incremental increase in bleeding risk with high NSAID dosages. The risk of serious bleeding was even greater when an NSAID is added to OAC therapy and aspirin. Seven out of 17 warfarin patients (41%) who were taking an NSAID also were on an antiplatelet agent. As a result of the pharmacist interventions, NSAIDs were discontinued in all of these patients, but the antiplatelet remained because of stent placement or carotid stenosis.

This analysis captured only those patients with a documented active prescription or self-reported OTC use of an NSAID. It is unknown how many patients might take OTC NSAIDs occasionally but not report this use to a provider or pharmacist. Primary care CPSs educate patients to not use NSAIDs while taking warfarin during their initial visit and periodically thereafter; however, with the number of different NSAIDs available without a prescription and the various brand and generic names offered, it can be difficult for patients to understand what they should or should not take for minor pain or fever. Therefore, it is imperative that NSAID use is reviewed regularly at anticoagulant follow-up visits and patients are educated about alternative OTC agents for pain relief (eg, acetaminophen, topical agents, heating pad) when necessary. It also is equally important for PCPs to weigh the benefit vs risk for each patient before prescribing an NSAID if alternatives have been exhausted especially if the patient also is taking an OAC and antiplatelet agent.

The smallest number of interventions completed was for BP management. According to the HAS-BLED bleeding risk score, BP management was recommended only if the most recent clinic SBP was > 160 mm Hg, excluding patients with documented white-coat syndrome or home SBP readings < 160 mm Hg. One potential explanation for the small number of patients with SBP > 160 mm Hg is that for many of the patients taking warfarin, the PC CPSs at CJZVAMC have been involved in their BP management through earlier consultation by providers.

Limitations

A limitation of the BP component of the HAS-BLED score was that the assessment of BP for this project was only one point in time. In 3 cases, the SBP was > 160 mm Hg only during the most recent measurement, and these patients had normal BP readings on return to the clinic for follow-up. This category of recommendation also took more time for follow-up because a PC CPS would need to evaluate the patient in clinic, implement changes to BP medications, and follow-up at subsequent visits. Although some PCPs felt that the patient did not need pharmacist intervention, the elevated SBPs were brought to the provider’s attention, and some patients received further monitoring by the PCP or through a specialty clinic (eg, nephrology).