Heart Transplantation Outcomes in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Potential Impact of Newer Antiviral Treatments After Transplantation

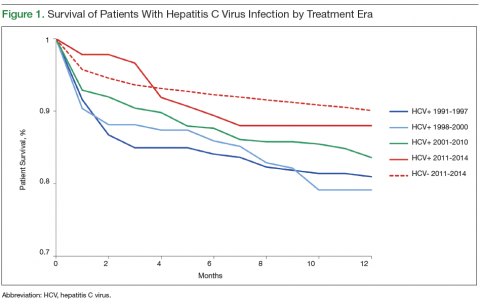

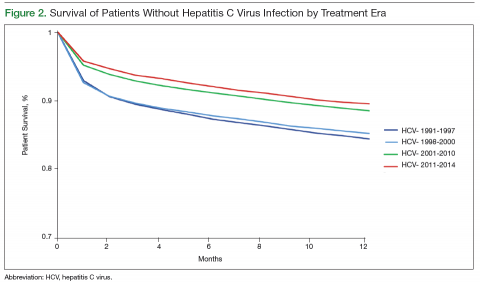

Survival data for the fourth treatment era (2011-2014) were available only for 1 and 2 years. HC+ patients’ survival rates were 89.01% (1 year) and 81.89% (2 years), and HC– patients’ rates were 91.00% (1 year) and 86.00% (2 years). The inferior survival found for the HC+ group during the 3 preceding eras was not found this era, during which HC+ and HC– patients had comparable rates of survival at 1 year (Figures 1 and 2).

Survival 1 year after HTx was compared between the HC+ and HC– groups over the 4 treatment eras (Figures 3 and 4). The HC+ patients’ survival after HTx improved from 81% during the earliest era (1991-1997) to 89% during the latest era (2011-2014), whereas HC– patients’ survival improved from 85% to 91% (P = .9).

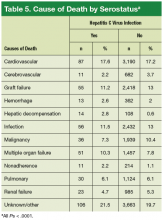

Hepatic decompensation leading to death was uncommon, but the rate was significantly higher (P = .0001) in the HC+ group (2.8%) than in the HC– group (0.6%).

Discussion

HCV infection is a risk factor for the development of cardiovascular illness and advanced heart failure. Given the worldwide prevalence of HCV infection, more HC+ patients will be evaluated for HTx in the future.2-4 Significant progress has been made in HCV infection treatment since the virus was first described. What was once incurable now has up to a 90% cure rate with newer treatment options.7,12,13 The present study findings showed consistent improvement in HC+ patients’ post-HTx survival during each treatment era. During the latest era, HC+ and HC– patients’ post-HTx survival was statistically similar.

It is possible that HC+ patients’ improvement in post-HTx survival could have resulted from improvement in overall post-HTx survival.14 Over the 23-year study period, the survival rates of both groups (HC+, HC–) improved, likely secondary to improved immunosuppression and perioperative care, but the magnitude of improvement was more pronounced in the HC+ group. HC+ patients’ post-HTx survival improved from 81% during the earliest era (1991-1997) to 89% during the latest era (2011-2014), whereas HC– patients’ survival improved from 85% to 91%. The improvement in HC+ patients’ short-term survival over the study period was substantial but did not reach statistical significance (P = .9).

Over the study period, the percentage of HC+ patients who underwent HTx remained low, ranging from 2.9% during the second era (1998-2000) to 1.7% during the fourth era (2011-2014). Overall, only 2.2% of study patients were HC+ at time of transplantation—a rate similar to previously reported rates.8,15 This rate likely represents a selection bias for HTx listing, in which patients with nearly normal liver function were selected for HTx, as evident by normal bilirubin levels in both groups. In the present study, a high proportion of HC+ patients were not white. This distribution also was noted in epidemiologic studies of HCV infection by ethnicity.6 In the U.S., the highest prevalence of HCV infection was noted in African Americans and the lowest in whites. According to the U.S. census report, African Americans constitute 12% of the total U.S. population,16 whereas 22% of HC+ patients are African American.1

It has been postulated that the immunosuppression that accompanies the post-HTx state accelerates HCV disease progression and shortens HC+ patients’ survival.17,18 These concerns were not validated in the most recent studies of kidney, liver, and heart transplantation in HC+ patients.15,19,20 Furthermore, where post-HTx cause of death was examined in HC+ patients, death was attributed primarily to post-HTx malignancy and bacterial sepsis but seldom directly to hepatic failure. In a study in which liver function was serially monitored after HTx in 11 HC+ patients, immunosuppression did not affect HCV disease progression, and there was no liver function impairment.15 In the same study, the 3 more recent HTx patients (of the 11) had their serial HCV viral load monitored. Viral load remained steady in 2 of the patients and decreased in the third. Similarly, there has been a theoretical concern that heightened immunologic status in HC+ patients might lead to more frequent rejection episodes. However, this concern has not been substantiated in reported studies.21,22 In the present study, the rate of graft failure as the cause of death was 11.2% in HC+ patients and 13% in HC– patients, though the difference was not statistically significant. Thus, concerns about HCV reactivation during immunocompromise or during increased allograft rejection were not substantiated.

Vasculopathy is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality after HTx and seems to be influenced by HC+. In a study of HC+ donor hearts transplanted to HC– patients, the prevalence of HCV infection in the recipients was 75% at a mean follow-up of 4.2 years.23 Serial angiogram showed coronary vasculopathy in 46% of HC+ patients and 24% of HC– patients 3.2 years after HTx.23 Similar concerns were raised in another small study, in which 2 of 4 HC+ patient deaths at 3.7-year follow-up were attributed to cardiovascular causes with features similar to those of transplantation vasculopathy.24 Those findings contrast with the present findings of cardiovascular deaths in 17.6% of HC+ patients and 17.2% of HC– patients. Outcomes similar to the present outcomes were reported by Lee and colleagues: Post-HTx cardiovascular deaths occurred in 16.4% of HC+ patients and 15.2% of HC– patients.8

Survival data on HC+ patients who undergo HTx are mixed, with some studies finding similar shortterm and midterm post-HTx survival21,22 and others finding decreased survival.8,9 It is difficult to interpret survival results from these studies, as some have included HCV infection that developed after HTx,9 and others have excluded early postoperative deaths from analysis.21 In addition, in the larger of these studies, which spanned 15 years, propensity matching was used for survival analysis. 8

It is possible that the selection and treatment of HC+ patients who were awaiting or underwent HTx changed over the study period. Thus, it might not be accurate to compare HTx outcomes of patients without considering the significant progress that has been made in the management of HCV infection. Although the present study’s aggregate (23-year) post-HTx survival results at 1, 5, and 10 years were similar to those reported in large series of HC+ patients who underwent HTx, the present early and intermediate survival results showed consistent improvements over time.8,9 This improvement in survival of HC+ patients was not examined in previous studies.

In the present study, the distribution of causes of post-HTx deaths was diverse (Table 5). Although the leading causes of death were cardiovascular or were related to sepsis or multi-organ failure, deaths attributed to liver failure were uncommon. Only 2.8% of deaths in the HC+ group and 0.6% of deaths in the HC– group were attributed to liver failure (P ≤ .001). These findings are similar to the cause-specific mortality reported in the literature.8,9,15,22 It is possible that these mortality results may be secondary to selection of patients with preserved liver function.

Future of HCV Infection and Heart Transplantation

Modern diagnostic methods will be used to accurately assess HC+ patients for HCV disease burden, and treatment will be provided before HTx is performed. Historically, the major limitations to treating HC+ patients awaiting HTx have been the long (48 week) duration of therapy and the anemia that can exacerbate heart failure symptoms and shorten the safe HTx waiting time.25 Most of the HCV treatment AEs have been attributed to use of IFN-α. Newer HCV treatments (direct-acting protease inhibitors without IFN) are of shorter duration (24 weeks) and have fewer AEs and higher cure rates. Most important, these treatments obtain similar cure rates irrespective of viral load, viral genotype, patient race, and previous HCV response status.7,12,13

Authors researching other solid-organ transplantation (eg, liver, kidney) have studied HCV pretreatment and found sustained virologic response before and after transplantation.26,27 Although these studies were conducted before the advent of direct-acting protease inhibitors, the feasibility of treating HCV before transplantation has been demonstrated.

Limitations

The limitations of retrospective data analysis are applicable to the present findings. Although HTx is infrequently performed in HC+ patients, the authors used a large national database and a 23-year study period and thus were able to gather a significant number of patients and perform meaningful statistical analysis. HCV disease burden, which influences disease progression, is much better quantified with recent quantitative viral loads, but these were not available in the UNOS database. It should be noted that UNOS does not gather information on HCV genotypes or forms of treatment received, both of which influence treatment response and prognosis. It is therefore not possible to elucidate, from the UNOS database, the influences of virus genotype and treatment response on post-HTx outcomes.

Conclusion

The treatment of HCV infection has significantly evolved since the virus was identified in 1989. At first the disease was considered incurable, but now a > 90% cure rate is possible with newer treatment regimens. This study found significant improvements in post-HTx outcomes in HC+ patients between 1991 and 2014. Both HC+ and HC– patients have had similar post-HTx clinical outcomes in recent years. The noted improvements in post-HTx survival in HC+ patients may be secondary to better patient selection or more effective antiviral treatments. Future studies will provide the answers.