Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 2

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

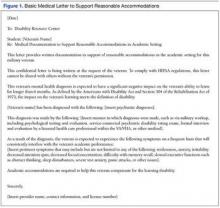

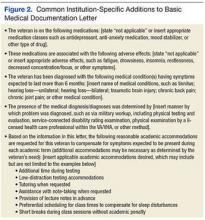

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from Katherine.Mitchell1@va.gov).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.