New Developments in Adult Vaccination: Challenges and Opportunities to Protect Vulnerable Veterans From Pneumococcal Disease

Immune-Compromised Adults

One of the shortcomings of PPSV-23 is its lack of efficacy in patients with advanced HIV, a group with an exquisite vulnerability to pneumococcal disease, as demonstrated by a randomized controlled trial of PPSV-23 in African patients with advanced, untreated HIV infection.21 Similarly, there is concern that patients with lymphoma, leukemia, multiple myeloma, and Hodgkin disease, also at high risk of pneumococcal infection, do not mount sufficient immune responses to polysaccharide antigens or that these responses are adversely affected by chemotherapy or immune suppressing medications. In these populations, a conjugate vaccine (PCV-7 or PCV-13) may elicit a more robust and durable immune response than a polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). A randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of PCV-7 in protecting patients with advanced HIV against pneumococcal disease in Africa.22 Based in part on this observation, the ACIP now recommends the use of PCV-13 in patients with HIV and other immunosuppressing conditions, including chronic renal failure.23 A direct comparison of the relative protection of PPSV-23 vs PCV-7 in this population has not been performed.

Pneumococcal Vaccines in the Elderly

Although PPSV-23 was widely adopted in the U.S. with the intention to protect adults aged > 65 years from pneumococcal infection, this vaccine did not achieve global appeal. In the Netherlands, for instance, PPSV-23 had very low penetration and was never endorsed by public health authorities. Concerns have been issued about the decreased immunogenicity of a polysaccharide vaccine in older adults, invoking the concept of immune senescence, a term that describes a diminished capacity to mount robust immune responses due to aging.

Protein-conjugated antigens, on the other hand, can elicit a better initial immune response than a polysaccharide vaccine can in an older adult. Whether the effect is sustained and translates to better clinical outcomes remains unknown. The adoption of PCV-13 and the continued role of PPSV-23 in adults aged > 65 years have been examined carefully by experts.24,25

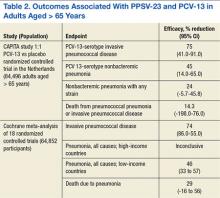

Dutch investigators organized the Community Acquired Pneumonia Immunization Trial in Adults (CAPITA), randomizing about 85,000 adults aged > 65 years toreceive eitherPCV-13 or a placebo.26 After 3 years of observation, the occurrence of invasive pneumococcal disease (caused by the vaccine serotypes) decreased by 85% in participants who received the vaccine compared with those who received a placebo. Additionally, the incidence of pneumococcal pneumonia (caused by the vaccine serotypes) decreased by 45% (Table 2). The findings of this trial largely inform the recommendation issued by APIC in October 2014 to administer PCV-13 vaccine to adults aged > 65 years.27

Polysaccharide Vaccine in Adults

A crucial limitation of the CAPITA study is that it does not provide a head-to-head comparison with PPSV-23. Similarly, the recommendation to use PCV-13 in patients with immune system compromising conditions did not arise from a direct comparison between PCV-13 and PPSV-23. In both groups of patients, ACIP continues to recommend PPSV-23 to extend protection to the 10 additional pneumococcal serotypes not included in PCV-13.28 Additionally, ACIP maintains its long-standing recommendation to administer PPSV-23 to adults aged < 65 years who have diabetes mellitus, or chronic liver, lung, or heart disease, or those who are tobacco smokers or misuse alcohol.

Notably, the order in which the vaccines are administered may influence their effectiveness. In adults aged 50 to 64 years, initial vaccination with PCV-13 followed by PPSV-23 lead to a better antipneumococcal immune response.14,29 Specifically, PCV-13 enhanced the response to subsequent administration of PPSV-23, whereas an initial PPSV-23 vaccine resulted in a decreased response to subsequent administration of PCV-13. After a 1-year interval between vaccines, immune titers to a second vaccination were not inferior.30 All the above considerations have shaped the ACIP recommendations for the administration of pneumococcal vaccines.27,31 Pneumococcal vaccination was a straightforward exercise when PPSV-23 was the only vaccine available for adults. The advent of PCV-13, however, renders pneumococcal immunization of adults more complicated (Figure 1).

Improving Vaccination Rates

The complex recommendations to vaccinate adults against pneumococcus may reveal obstacles to effective pneumococcal vaccination programs.32 From the perspective of health care institutions, the adoption of the new pneumococcal vaccine implies an added cost. A pneumococcal vaccination strategy that incorporates PCV-13 may be cost-effective, at least under certain parameters.33-35 There remains, however, the issue of affordability and the opportunity cost—the need to decrease funding for other health care programs to accommodate an increased budget for pneumococcal vaccination. Logistically, maintaining a reliable supply of vaccines to meet the demand of practitioners at various sites requires careful planning. Consequently, tracking vaccinated and unvaccinated patients and carefully coordinating among clinical providers, nurses, and pharmacists are essential.