When is catheter ablation a sound option for your patient with A-fib?

Ablation sits far along on the spectrum of atrial fibrillation therapy, where its indications and potential efficacy call for careful consideration.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

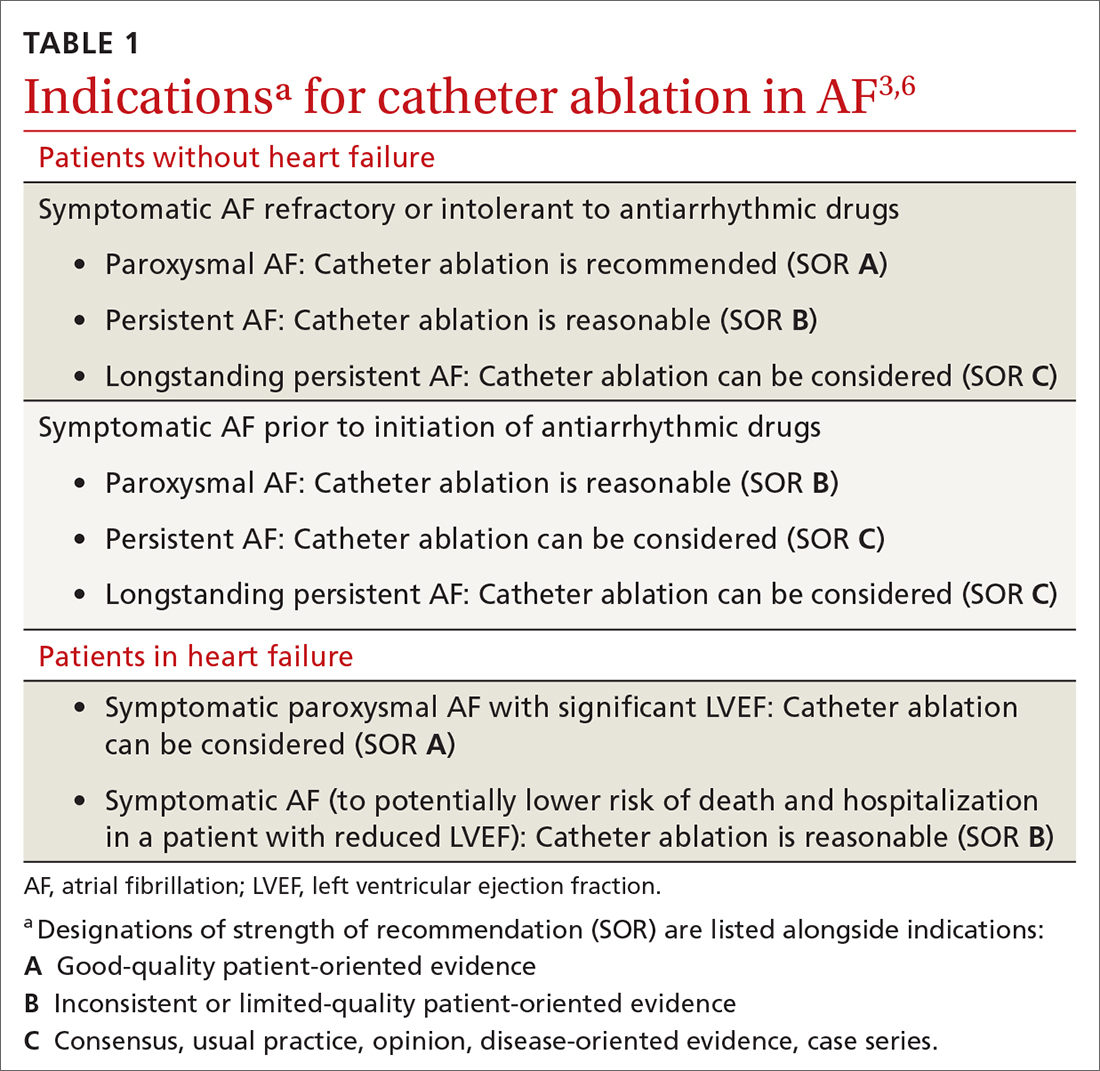

› Refer patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) to Cardiology for consideration of catheter ablation, a recommended treatment in select cases of (1) symptomatic paroxysmal AF in the setting of intolerance of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and (2) persistence of symptoms despite antiarrhythmic drug therapy. A

› Continue long-term oral anticoagulation therapy post ablation in patients with paroxysmal AF who have undergone catheter ablation if their CHA2DS2–VASc score is ≥ 2 (men) or ≥ 3 (women). C

› Regard catheter ablation as a reasonable alternative to antiarrhythmic drug therapy in select older patients with AF, and refer to a cardiologist as appropriate. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

In patients who progress from paroxysmal to persistent AF (see “Subtypes,” below), 2 distinct pathways, facilitated by the presence of abnormal tissue, continuously activate one another, thus maintaining the arrhythmia. Myocardial tissue in the pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF (see “Rhythm control”).

Subtypes. For the purpose of planning treatment, AF is classified as:

- Paroxysmal. Terminates spontaneously or with intervention ≤ 7 days after onset.

- Persistent. Continuous and sustained for > 7 days.

- Longstanding persistent. Continuous for > 12 months.

- Permanent. The patient and physician accept that there will be no further attempt to restore or maintain sinus rhythm.

Goals of treatment

Primary management goals in patients with AF are 2-fold: control of symptoms and prevention of thromboembolism. A patient with new-onset AF who presents acutely with inadequate rate control and hemodynamic compromise requires urgent assessment to determine the cause of the arrhythmia and need for cardioversion.3 A symptomatic patient with AF who does not have high-risk features (eg, valvular heart disease, mechanical valves) might be a candidate for rhythm control in addition to rate control.3,4

Rate control. After evaluation in the hospital, a patient who has a rapid ventricular response but remains hemodynamically stable, without evidence of heart failure, should be initiated on a rate-controlling medication, such as a beta-blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker. A resting heart rate goal of < 80 beats per minute (bpm) is recommended for a symptomatic patient with AF. The heart rate goal can be relaxed, to < 110 bpm, in an asymptomatic patient with preserved left ventricular function.5,6

Rhythm control, indicated in patients who remain symptomatic on rate-controlling medication, can be achieved either with an antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) or by catheter ablation.4,5 In stable patients, rhythm control should be considered only after a thorough work-up for a reversible cause of AF, and can be achieved with an oral AAD or, in select patients, through catheter ablation (TABLE 13,6). Other indications for chronic rhythm control include treatment of patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.5

A major study that documented the benefit of early rhythm control evaluated long-term outcomes in 2789 patients with AF who were undergoing catheter ablation.7 Patients were randomized to early rhythm control (catheter ablation or AAD) or “usual care”—ie, in this study, rhythm control limited to symptomatic patients. Primary outcomes were death from cardiovascular causes, stroke, and hospitalization with worsening heart failure or acute coronary syndrome. A first primary outcome event occurred in 249 patients (3.9/100 person-years) assigned to early rhythm control, compared to 316 (5.0 per 100 person-years) in the group assigned to usual care.

The study was terminated early (after 5.1 years) because of overwhelming evidence of efficacy (number need to treat = 7). Although early rhythm control was obtained through both catheter ablation and AAD (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.79; 96% CI, 0.66-0.94; P = .005), success was attributed to the use of catheter ablation for a rhythm-control strategy and its use among patients whose AF was present for < 1 year. Most patients in both treatment groups continued to receive anticoagulation, rate control, and optimization of cardiovascular risk.7

Continue to: Notably, direct studies...