Critical Care in the ED: Mechanical Ventilation, Sepsis, Neurological Hypertensive Emergencies, and Pressors in Shock

The tremendous overlap between the specialties of emergency medicine and critical care medicine is particularly apparent in the initial resuscitation of critically ill patients—a vulnerable population in which the early period of care has significant impact on outcomes.

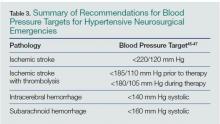

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

There are no large recent studies in the literature on antihypertensive therapy in SAH. The AHA/ASA guidelines updated in 2012 reflect the consensus that elevated BPs are associated with increased risk of aneurysmal rebleeding and thus poorer patient-oriented outcomes. The consensus remains to use a titratable agent to target a systolic BP less than 160 mm Hg until definitive neurosurgical therapy, such as aneurysmal coiling or clipping.36 Given the variability of the sodium nitroprusside dose-response relationship, IV labetalol, and nicardipine, are recommended agents for continuous control, though data showing differences in mortality and/or disability are lacking.36 Again, retrospective data suggest that BP variability negatively impacts mortality and disability, so consider early initiation of continuous infusions to achieve and maintain consistency in the chosen target.44

Summary

,Pressors in the Management of Hypotension

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is one of the most commonly used agents for shock in the ED, with indications spanning multiple etiologies. It is an endogenous neurotransmitter that works predominantly on a1 receptors as well as exerting some modest effects on b1 and b2 receptors, for combined vasopressor and improved cardiac contractility effect.46-47 Norepinephrine is currently the recommended initial agent for sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion.24 However, a recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis supports evidence of limited differences among various pressors.48 Several comparative randomized control trials show norepinephrine is as effective as other agents, but with fewer side effects.24,49 With the ease and familiarity of its use by most EPs, and a wide therapeutic index for targeted effect versus arrhythmias, norepinephrine is a reasonable choice as the initial pressor in managing a wide variety of shock syndromes.

Vasopressin

Another commonly used agent in the treatment of shock, vasopressin is an analogue of the antidiuretic hormone secreted from the posterior pituitary gland, exerting its CV effects primarily as a vasoconstrictor by increasing intracellular calcium.50 Vasopressin doses are 0.03 or 0.04 U/min IV without titration.24,50 Early studies of septic patients demonstrated a relative deficiency of serum vasopressin levels, leading clinicians to utilize it in the treatment of sepsis-induced shock. However, the Vasopressin and Septic Shock Trial (VASST) trial demonstrated that the addition of vasopressin to norepinephrine did not produce any improvements in morbidity or mortality compared with norepinephrine alone.51 Despite these findings, vasopressin is still commonly used as a secondary agent to correct continued hypotension. Vasopressin may be appropriate for patients who specifically require peripheral vasoconstriction in the setting of good cardiac output and volume status, ability to tolerate increases in afterload, or in patients at risk for dysrhythmias.

Dopamine

Dopamine had been previously recommended as the initial choice of pharmacologic support for the management of shock.24,52-54 Dopamine is an adrenergic agonist agent that works via a1 and b1 receptors as well as a precursor to the synthesis of norepinephrine and epinephrine.55 There are dose-dependent effects on various receptors from escalating amounts administered,55-56 but the literature does not support the concept of “renal-dose” dopamine.57-59 A study by DeBaker et al49 suggested no difference in efficacy between dopamine and norepinephrine, but demonstrated a greater tendency toward cardiac dysrhythmias with dopamine. For these reasons noted above, norepinephrine may be the initial agent for pharmaceutical support of shock, particularly in septic syndromes, with dopamine as a secondary or adjunct agent in patients at low risk for tachyarrhythmia or a relative bradycardia. 24, 56