How to Avoid the Mistakes That Everyone Makes

Through a series of case scenarios, the author illustrates five common biases that can lead to preventable medical errors.

This case emphasizes the impact of “framing bias” in the thought process that led to the initial diagnosis of ascending cholangitis. Charcot’s Triad of fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain was the “frame” in which the suspected—yet uncommon—diagnosis was made. The frame of reference, however, changed significantly when the additional information of P. falciparum malaria exposure was elucidated, allowing the correct diagnosis to come into view.

I “Framing Bias” Mitigation Strategy: Confirm that the points of data align properly and fit within the diagnostic possibilities. If they do not connect, seek further information and widen the frame of reference.

Case Scenario 4: Mother Knows Best

,The parents of an 11-year-old boy brought their child to the ED for abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that started 10 hours prior to presentation. The boy had no medical or surgical history. During the examination, his mother expressed concern for appendicitis, a common concern of parents whose children have abdominal pain.

Although the boy was uncomfortable, he had no right lower-quadrant tenderness; his bowel sounds were normal, and there was no tenderness to heel tap or Rovsing’s sign. He did have periumbilical tenderness and distractible guarding. His white blood-cell (WBC) count was 12.5 K/uL with 78% segmented neutrophils and urinalysis showed 15 WBCs/hpf with no bacteria. With IV hydration, opioid pain medication, and antiemetic medication, the patient felt much better, and the abdominal examination improved with no tenderness.

After a clear liquid trial was successful, careful counseling of the parents made it clear that appendicitis was possible, but unlikely given the improvement in symptoms, and the boy was discharged with the diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. Six hours later, the boy was brought back to the ED and then taken to the operating room for acute appendicitis.

This case illustrates the effect of “confirmation bias,” in which the preference to favor a particular diagnosis outweighs the clinical clues that suggested the correct diagnosis. Neither possible opioid effect in masking pain nor the lack of history or complaint of diarrhea was effectively taken into consideration before making the diagnosis of “gastroenteritis.”

I “Confirmation Bias” Mitigating Strategy: Be aware that selective filtering of information to confirm a belief is wrought with danger. Seek data and information that could weaken or negate the belief and give it serious consideration.

Case Scenario 5: The “Frequent Flyer”

This case involved an extremely difficult-to-manage patient who had presented to the ED many times in the past with “the worst headache of his life.” During these visits, he was typically disruptive, problematic to discharge safely, and a particular behavioral issue for the nurses. As a result, when he presented to the ED, the goal was to evaluate him quickly, treat him humanely, and diagnose and discharge him as soon as possible. He was never accompanied by family or friends. His personal medical history was positive for uncontrolled hypertension and chronic alcoholism.

Attempts to coordinate his care with social services and community mental health were unsuccessful. On examination, his blood pressure was 210/105 mm Hg and a severe headache was once again his chief complaint. A head CT scan performed less than 12 hours prior to this presentation revealed no new findings compared with many prior CTs. However, there was a slight slurring of his speech on this visit that wasn’t part of his prior presentations. After he was given lorazepam and a meal tray, the patient felt a little better and was discharged. The patient never returned to the ED, and the staff has since become concerned that on this last ED visit, their “frequent flyer” had something real.

Although it is not known what exactly happened to this patient, the manner in which he was treated represents the effect of premature closure on the medical decision-making process. When a clinician jumps to conclusions without seeking more information, the possibility of an error in judgment exists.

I “Premature Closure” Mitigating Strategies: Never stop thinking even after a conclusion has been reached. Instead, stop and think again about what else could be happening.

Conclusion

In all of the case scenarios presented, any or all of the patients might have survived the errors made without any adverse outcome, but the errors might also have resulted in mild to severe permanent disability or death. It is important to remember that errors can happen regardless of good intentions and acceptable practice, and that although an error may have no consequence in one set of circumstances, the same error could be deadly in others.

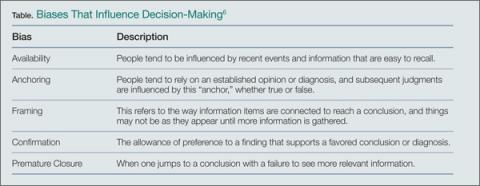

On the systems level, approaches to assess and control the work environment are necessary to mitigate risk to individuals, create a culture of safety, and encourage collective learning and continuous improvement. Recognition of the frequent incidence of error and awareness of the overlapping cognitive biases (Table), while always being mindful to take a moment to think further, can help avoid—but never eliminate--these types of mistakes.