Who Overdoses on Opioids at a VA Emergency Department?

Results

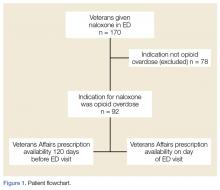

The ED at the George E. Wahlen VAMC averages 64 visits per day, almost 94,000 visits within the study period. One hundred seventy ED visits between January 1, 2009 and January 1, 2013, involved naloxone administration. Ninety-two visits met the inclusion criteria of opioid overdose, representing about 0.002% of all ED visits at this facility (Figure 1). Six veterans had multiple ED visits within the study period, including four veterans who were in the opioid-only group.

The majority of veterans in this study were non-Hispanic white (n = 83, 90%), male (n = 88, 96%), with a mean age of 63 years. Less than 40% listed a next of kin or contact person living at their address.

Based on prescriptions available within 120 days before the overdose, 67 veterans (73%) possessed opioid and/or BZD prescriptions. In this group, the MED available on the day of the ED visit ranged from 7.5 mg to 830 mg. The MED was less than or equal to 200 mg in 71.6% and less than or equal to 50 mg in 34.3% of these cases. Veterans prescribed both opioids and BZDs had higher MED (average, 259 mg) available within 120 days of the ED visit than did those prescribed opioids only (average, 118 mg) (P = .015; standard deviation [SD], 132.9). The LED ranged from 1 mg to 12 mg for veterans with available BZDs.

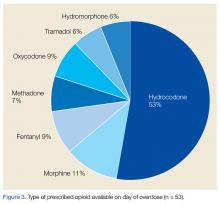

Based on prescriptions available on the day of opioid overdose, 53 veterans (58%) had opioid prescriptions. The ranges of MED and LED available on the day of overdose were the same as the 120-day availability period. The average MED was 183 mg in veterans prescribed both opioids and BZDs and 126 mg in those prescribed opioids only (P = .283; SD, 168.65; Figure 2). The time between the last opioid fill date and the overdose visit date averaged 20 days (range, 0 to 28 days) in veterans prescribed opioids.

All veterans had at least one diagnosis that in previous studies was associated with increased risk of overdose.9,15 The most common diagnoses included CVD, mental health disorders, pulmonary diseases, and cancer. Other SUDDs not including tobacco use were documented in at least half the veterans with prescribed opioids and/or BZDs. No veteran in the sample had a documented history of opioid SUDD.

Hydrocodone products were available in greater than 50% of cases. None of the veterans were prescribed buprenorphine products; other opioids, including tramadol, comprised the remainder (Figure 3). Primary care providers prescribed 72% of opioid prescriptions, with pain specialists, discharge physicians, ED providers, and surgeons prescribing the rest. When both opioids and BZDs were available, combinations of a hydrocodone product plus clonazepam or lorazepam were most common.

Overall, 64% of the sample had UDS results prior to the ED visit. Of veterans prescribed opioids and/or BZDs, 53% of UDSs reflected prescribed regimens.

On the day of the ED visit, 1 death occurred. Ninety-one veterans (99%) survived the overdose; 79 veterans (86%) were hospitalized, most for less than 24 hours.

Discussion

This retrospective review identified 92 veterans who were treated with naloxone in the ED for opioid overdose during a 4-year period at the George E. Wahlen VAMC. Seventy-eight cases were excluded because the reason entered in charts for naloxone administration was itching, constipation, altered mental status, or unclear documentation.

Veterans in this study were, on average, older than the overdose fatalities in the United States. Opioid-overdose deaths in all US states and in Utah alone occur most frequently in non-Hispanic white men aged between 35 and 54 years.7,22,23 In the 2010 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample of 136,000 opioid overdoses, of which 98% survived, most were aged 18 to 54 years.16 The older age in this study most likely reflects the age range of veterans served in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA); however, as more young veterans enter the VHA, the age range of overdose victims may more closely resemble the age ranges found in previous studies. Post hoc analysis showed eight veterans (9%) with probable intentional opioid overdose based on chart review, whereas the incidence of intentional prescription drug overdose in the United States is 17.1%.24

In Utah, almost 93% of fatal overdoses occur at a residential location.22 Less than half of the veterans in this study had a contact or next of kin listed as living at the same address. Although veterans may not have identified someone living with them, in many cases, it is likely another person witnessed the overdose. Relying on EMRs to identify who should receive prevention education in addition to the veteran, may result in missed opportunities to include another person likely to witness an overdose.25 Prescribers should make a conscious effort to ask veterans to identify someone who may be able to assist with rescue efforts in the event of an overdose.

Diagnoses associated with increased risk of opioid-overdose death include sleep apnea, morbid obesity, pulmonary disease or CVD, and/or a history of psychiatric disorders and SUDD.8,9,16 In a large sample of older veterans, only 64% had at least one medical or psychiatric diagnosis.26 Less than half of the 18,000 VA primary care patients in five VA centers had any psychiatric condition, and less than 65% had CVD, pulmonary disease, or cancer.27 All veterans in this study had medical and psychiatric comorbidity.

In contrast, a large ED sample described by Yokell et al16 found chronic mental conditions in 33.9%, circulatory disorders in 29.1%, and respiratory conditions in 25.6% of their sample. Bohnert et al9 found a significantly elevated hazard ratio (HR) for any psychiatric disorder in a sample of nearly 4,500 veterans. There was variation in the HR when individual psychiatric diagnoses were broken out, with bipolar disorder having the largest HR and schizophrenia having the lowest but still elevated HR.9 In this study, individual diagnoses were not broken out because the smaller sample size could diminish the clinical significance of any apparent differences.

Edlund et al10 found that less than 8% of veterans treated with opioids for chronic noncancer pain had nonopioid SUDD. Bohnert et al9 found an HR of 21.95 for overdose death among those with opioid-use disorders. The sample in this study had a much higher incidence of nonopioid SUDD compared with that of the study by Edlund et al,10 but none of the veterans in this study had a documented history of opioid-use disorder. The absence of opioid-use disorders in this sample is unexpected and points to a need for providers to screen for opioid-use disorder whenever opioids are prescribed or renewed. If prevention practices were directed only to those with opioid SUDDs, none of the veterans in this study would have been included in those efforts. Non-SUDD providers should address the risks of opioid overdose in veterans with sleep apnea, morbid obesity, pulmonary disease or CVD, and/or a history of psychiatric disorders.

Gomes et al18 found that greater than 100 mg MED available on the day of overdose doubled the risk of opioid-related mortality. The VA/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain identifies 200 mg MED as a threshold to define high-dose opioid therapy.28 Fulton-Kehoe et al29 found that 28% of overdose victims were prescribed less than 50 mg MED. In this study, the average dose available to veterans was greater than 100 mg MED; however, one-third of all study veterans had less than 50 mg MED available. Using a threshold dose of 50 mg MED to target prevention efforts would capture only two-thirds of those who experienced overdose; a 200-mg MED threshold would exclude the majority, based on the average MED in each group in this study. Overdose education should be provided to veterans with access to opioids, regardless of dose.

Use of BZDs with opioids may result in greater central nervous system (CNS) depression, pharmacokinetic interactions, or pharmacodynamic interactions at the µ- opioid receptor.30-32 About one-third of veterans in this study were prescribed opioids and BZDs concurrently, a combination noted in about 33% of opioid overdose deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.24 Individuals taking methadone combined with BZDs have been found to have severe medical outcomes.33 If preventive efforts are targeted to those receiving opioids and other CNS depressants, such as BZDs, about half (42%) of the veterans in this study would not receive a potentially life-saving message about preventing overdoses. All veterans with opioids should be educated about the additional risk of overdose posed by drug interactions with other CNS depressants.

The time since the last fill of an opioid prescription ranged from 0 to 28 days. This time frame indicates that some overdoses may have occurred on the day an opioid was filled but most occurred near the end of the expected days’ supply. Because information about adherence or use of the opioid was not studied, it cannot be assumed that medication misuse is the primary reason for the overdose. Providing prevention efforts only at the time of medication dispensing would be insufficient. Clinicians should review local and remote prescription data, including via their states’ prescription drug monitoring program, when discussing the risk of overdose with veterans.

Most veterans had at least one UDS result in the chart. Although half the UDSs obtained reflected prescribed medications, the possibility of aberrant behaviors, which increases the risk of overdose, cannot be ruled out with the methods used in this study.34 Medication management agreements that require UDSs for veterans with chronic pain were not mandatory at the George E. Wahlen VAMC during the study period, and those used did not mandate discontinuation of opioid therapy if suspected aberrant behaviors were present.

A Utah study based on interviews of overdose victims’ next of kin found that 76% were concerned about victims’ aberrant behaviors, such as medication misuse, prior to the death.22 In contrast, a study of commercial and Medicaid recipients estimated medication misuse rates in at or less than 30% of the sample.35 Urine-drug screening results not reflective of the prescribed regimens have been found in up to 50% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy.

The UDS findings in this study were determined by the authors and did not capture clinical decisions or interpretations made after results were available or whether these decisions resulted in overdose-prevention strategies, such as targeted education or changes in prescription availability. Targeting preventive efforts toward veterans only with UDS results suggesting medication misuse would have missed more than half the veterans in this study. Urine-drug screening should be used as a clinical monitoring tool whenever opioids, BZDs, or other substances are used or prescribed.

The VA now has a nationwide program, Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND), promoting overdose education and take-home naloxone distribution for providers and patients to prevent opioid-related overdose deaths. A national SharePoint site has been created within the VA that lists resources to support this effort.

Almost all veterans in this review survived the overdose and were hospitalized following the ED visit. Other investigators also have found that the majority (51% to 98%) of overdose victims reaching the ED survived, but fewer patients (3% to 51%) in those studies were hospitalized.16,36 It is unknown whether there are differences in risk factors associated with survived or fatal overdoses.