Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in a 24-Year-Old Woman

Diagnosis

Imaging Studies. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) imaging studies do not typically demonstrate any abnormal findings.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show some inconsistent and subtle findings, such as flattening of the backs of the eyeballs, empty sella, or tortuous optic nerves.1

Lumbar Puncture. On LP, a very high opening pressure is a hallmark of IIH. An opening pressure <20 cm H2O is generally considered normal, 20 cm to 25 cm H2O is “equivocal,” and >25 cm H2O is abnormal.7 Patients presenting with IIH commonly have an opening pressure that exceeds 200 cm H2O.1-3 Extremely high pressures, however, are not required for the diagnosis, but some elevations in opening pressure will always be present.2,5 With the exception of a high opening pressure, the patient’s CSF analysis is normal.

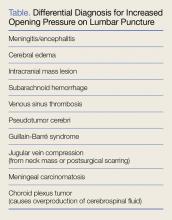

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, one that is made after exclusion of all other potential causes of increased ICP (Table). Since contrast CT and MRI can identify subtle anatomical deformities and small lesions, their absence on these studies can help establish a diagnosis of IIH.

Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Venous sinus thrombosis is a rare but devastating condition that also cannot be diagnosed from a noncontrast CT but must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of IIH.8-10 Venous sinus thrombosis is characterized by a clot in one of the large venous sinuses that drain blood from the brain; the clot causes pressure to back up into the smaller cerebral vasculature, eventually inducing either a hemorrhagic stroke from a stressed vessel rupturing, or an ischemic stroke from lack of blood flow to the affected area of the brain. This condition is even more rare than IIH (0.5 cases per 100,000 population), but it can be devastating if missed, carrying a mortality rate as high as 15% in some studies.11

Risk Factors

Risk factors known to cause cerebral venous clots include genetic thrombophilias, pregnancy or recent pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, inflammatory bowel disease, severe dehydration, local infection/trauma, and substance abuse. Regardless of risk factors, the most recent guidelines of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommend imaging studies of the cerebral venous sinuses for any patient presenting with new-onset symptoms suggestive of IIH (Class 1, Level of Evidence C).11 The two imaging options for evaluation of the cerebral venous sinuses are CT venography or MR venography. Since the 2013 American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria do not indicate a preference of one modality over the other, the choice of can be left to your radiologist.12

Patient Disposition

Patients with IIH typically do not require inpatient admission. Only about 3% of IIH patients will have a fulminant course of rapid-onset of vision loss, but even the most severe and acute cases will deteriorate over weeks, not hours or days.13 Nevertheless, close neurology follow-up is essential. If rapid and thorough outpatient neurological care is unavailable, admission is required.

Management

Not every patient with IIH experiences amelioration or resolution of symptoms following an LP; moreover, there is no clear way to differentiate patients who will experience therapeutic effects from LP from those who will not. Serial LPs as treatment for IIH have been discussed in the literature, but a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is a more practical approach in patients who do not respond to an initial LP.2,14

CSF Volume. The volume of CSF that can be removed safely may be 15 to 25 mL or more. A 1974 paper by Johnston and Paterson15 described five pseudotumor patients whose CSF was drained until their pressure had normalized; the amount removed varied from 15 to 25 mL, without adverse effects. A 1975 case series by Weisberg6 described safe removal of up to 30 mL of CSF in pseudotumor patients—the precise amount removed was determined by that which was necessary to lower the CSF pressure into the normal range. In 2007, a case report by Aly and Lawther16 of a pregnant woman with IIH describes twice weekly LP drainage of 30 mL.

There is nothing in the current literature to suggest that removing 10 to 30 mL of CSF instead of the 4 to 8 mL typically drawn in a diagnostic LP is going to pose any risk to the patient. The main complication associated with therapeutic LP is post-LP headache.5,17,18 There are currently no studies documenting outcomes after specific amounts of CSF removal.

Lifestyle Modifications: Weight Loss. No prospective, randomized controlled trials have proven weight loss to be effective in ameliorating the symptoms of IIH; however, several studies have found that rapid weight loss—whether through aggressive dieting or gastric bypass surgery—can improve symptoms dramatically within several months.19,20 One small study by Johnson et al has suggested that a 6% weight reduction is associated with marked improvement in papilledema.21Pharmacotherapy. The accepted first-line medication to alleviate symptoms of IIH is acetazolamide, and its use is supported by a recent randomized controlled trial conducted by the Neuro-Ophthalmology Research Disease Investigator Consortium (NORDIC).22 Most neurologists will administer a starting dose of acetazolamide 500 mg twice a day, and then increase the dose until symptoms are controlled or adverse effects appear (eg, fatigue, nausea/vomiting/diarrhea, electrolyte abnormalities, kidney stones) that contraindicate further dosage increases. In the NORDIC trial, patients were given up to 4 g of acetazolamide daily.22

Other medications, including loop diuretics and corticosteroids, should not be used except under the direct supervision of a neurologist.2,14