ED-to-ED Transfers: Optimizing Patient Safety

Case Commentary

In this case, when the nursing assessment preceding transfer revealed sustained abnormal vital signs particularly the significant hypertension, reassessment and blood pressure management by the sending EP prior to transport may have diminished the poor outcome resulting from the intracranial hemorrhage. Ideally, BP control should have been implemented prior to transport—especially in the context of possible arterial dissection/occlusion with ongoing anticoagulation therapy. If such attempts to control BP prior to transport prove inadequate, a hand-off communication with the receiving EP is indicated, emphasizing the need for immediate evaluation and critical intervention upon patient arrival. On the receiving end of a patient transfer, it is good practice that all critically ill or injured patients be immediately assessed upon arrival at the ED, regardless of planned interventions by any other department.

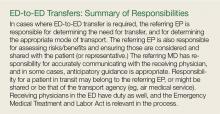

Transport from another ED cannot mislead to a false sense of security that ED care is completed. Patients geographically located in the ED (especially those who are newly arrived) are the responsibility of the ED providers until that point where the next specialist provider clearly assumes care of the patient (see “ED-to-ED Transfers: Summary of Responsibilities”). This point in handoff time can be murky and unclear; yet, as illustrated by this case, it is best to re-evaluate and ensure appropriate emergency care of the patient upon arrival. In addition, as with any other ED patient with a change in condition, timely re-evaluation of the transferred patient is indicated upon receiving the report from nursing that the patient’s condition had changed.

Transfers between EDs should be viewed as a process, and that each phase in the process is important—from the pre-transfer preparation at the sending facility, the physical transfer itself by transport personnel, and the post-transfer arrival that requires the receiving facility to ensure care continues seamlessly and appropriately. Even in situations of high acuity and/or high volume, anticipation and timely attention is required by the receiving staff to ensure continuity of safe patient care. The metaphorical baton was dropped in this transfer.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. The sending facility should always address any abnormal vital signs prior to patient transfer. The receiving facility should evaluate all transferred patients at the bedside as soon as possible upon arrival. Both facilities should take timely advantage of the information the nurses provide, especially when there is a change in the patient’s condition. All involved physicians from the sending facility should communicate to the receiving ED staff critical and potentially critical patient care information and concerns that pose a risk of deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Case 2

A 23-year-old woman presented to a community hospital ED with a sore throat, fever, and difficulty swallowing. The PA on duty saw the patient in the fast track section of the ED. The patient reported the sore throat had been persistent for the past 3 days, and that she began having difficulty swallowing the day of presentation. Her reported temperature at home was 102°F, but the patient said she had been unable to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen because it was too painful to swallow. The patient had no significant medical history and reported no known recent streptococcal exposure. She denied alcohol use, but admitted to smoking an average of 10 cigarettes per day.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: HR, 92 beats/min; RR, 11 breaths/min; BP, 122/65 mm Hg; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. She was not drooling or tripoding. Throat examination revealed posterior oropharyngeal erythema, edema, and exudate, with a uvula displaced to the left with a right-sided asymmetric tonsillar swelling consistent with a significant peritonsillar abscess. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Rapid strep and monospot testing were negative; the patient’s WBC was 9.1 x 109/L with a normal differential. After discussion with the attending EP, an IV line was started, and clindamycin 900 mg and dexamethasone 10 mg were administered. Arrangements were made with the university hospital ED for ALS ambulance transfer, as there were no otolaryngologist services available at the community hospital.

Upon arrival, the patient was examined by the university attending EP and was found to have mild asymmetry of the tonsils, but no midline disruption or uvula shift. The patient was given advice on symptomatic management and was discharged home.

Case Commentary

It is likely that transfer of this patient and its inherent risks could have been averted had the community EP personally assessed the patient prior to transfer arrangements. Supervision of physician extenders and residents in the ED may present challenges to patient safety, diagnostic accuracy, and appropriate treatment, especially in this era of volume and time-driven throughput metrics.