Burnout among surgeons: Lessons for psychiatrists

This review summarizes risk factors and identifies potential interventions.

Institutional and organizational factors

Eighteen studies3,13,14,18,20,22,23,29,30,36-38,44,45,47,54,56,57 examined how different organizational factors play a role in burnout. Four studies3,13,20,37 discussed administrative/bureaucratic work, 420,45,54,57 mentioned electronic medical documentation, 222,30 covered duty hour regulations, 318,45,57 discussed mistreatment of physicians, and 613,18,23,44,47,56 described the importance of workplace support in addressing burnout.

Physical and mental health factors

Eighteen studies6,7,14,15,17,20,26,27,29,34,43,44,48,52,54,57-59 discussed aspects of physical and mental health linked to burnout. Among these, 334,43,59 discussed the importance of physical health and focused on how improving physical health can reduce stress and burnout. Three studies6,17,58 noted the prevalence of suicidal ideation in both residents and attendings experiencing prolonged burnout. Five studies26,29,43,44,48 described the systematic barriers that inhibit physicians from getting professional help. Two studies7,27 reported marital status as a factor for burnout; participants who were single reported higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation. Five studies6,14,15,54,57 outlined how depression is associated with burnout.

Strategies to mitigate burnout

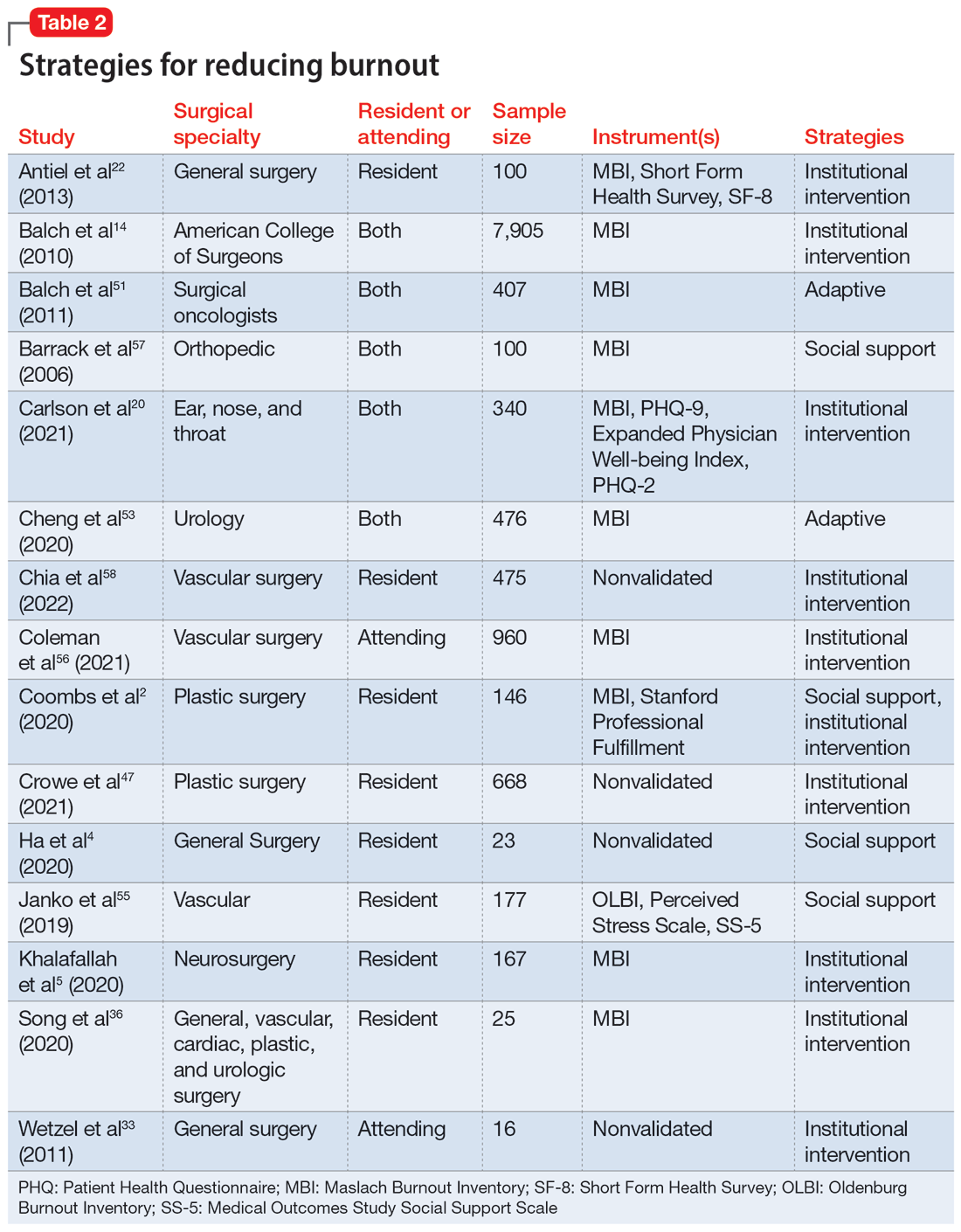

Fifteen studies

Take-home points

Research that focused on work/life balance and burnout found excessive time commitment to work is a major factor associated with poor work/life balance. Residents who worked >80 hours a week had a significantly higher burnout rate.56 One study found that 70% of residents reported not getting enough sleep, 30% reported not having enough energy for relationships, and 39% reported that they were not eating or exercising due to time constraints.4 A high correlation was found between the number of hours worked per week and rates of burnout, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are aspects of burnout measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).24 The excessive time commitment to work not only contributes to burnout but also prevents physicians from getting professional help. In 1 study, both residents (56%) and attendings (24%) reported that 1 of the biggest barriers to getting help for their burnout symptoms was the inability to take time off.34 Research indicates that the hours worked per week and work/home conflicts were independently associated with burnout and career satisfaction.15 A decrease of weekly work hours may give physicians time to meet their responsibilities at work and home, allowing for a decrease in burnout and an increase in career satisfaction.

Increased work hours have also been found to be correlated with medical errors. One study found that those who worked 60 hours per week were significantly less likely to report any major medical errors in the previous 3 months compared with those who worked 80 hours per week.9 The risk for the number of medical errors has been reported as being 2-fold if surgeons are unable to combat the burnout.49 On the other hand, a positive and supportive environment with easy access to resources to combat burnout and burnout prevention programs can reduce the frequency of medical errors, which also can reduce the risk of malpractice, thus further reducing stress and burnout.43

Continue to: In response to resident complaints...