Malingering in apparently psychotic patients: Detecting it and dealing with it

Look for external incentives, atypical hallucinatory symptoms described by the patient

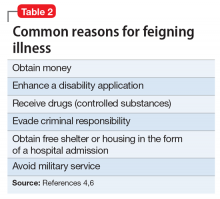

Know the real thing

Clinicians first must have the clinical acumen and expertise to identify a true mental illness such as psychosis2 (Table 1). The differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms is broad. The astute clinician might suspect that untreated bipolar disorder or depression led to the emergence of perceptual disturbances or disordered thinking. Transient psychotic symptoms can be associated with trauma disorders, borderline personality disorder, and acute intoxication. Psychotic spectrum disorders range from brief psychosis to schizophreniform to schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

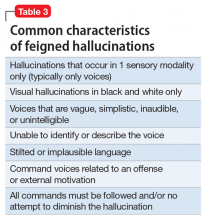

Malingering—which is a condition, not a diagnosis—is characterized by the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives.3,4 The presence of external incentives differentiates malingering from true psychiatric disorders, including factitious disorder, somatoform disorder, and dissociative disorder, and specific medical conditions.1 In those disorders, there is no external incentive.

It is important to remember that malingering can coexist with a serious mental illness. For example, a truly psychotic person might malinger, feign, or exaggerate symptoms to try to receive much needed help. Individuals with true psychosis might have become disenchanted with the mental health system, and thereby have a tendency to over-report or exaggerate symptoms in an effort to obtain treatment. This also could explain why many clinicians intuitively are reluctant to make the determination that someone is malingering. Malingering also can be present in an individual who has antisocial personality disorder, factitious disorder, Ganser syndrome, and Munchausen syndrome.4 When symptoms or diseases that either are thought to be exaggerated or do not exist, consider a diagnosis of malingering.

A key challenge in any discussion of abnormal health care–seeking behavior is the extent to which a person’s reported symptoms are considered to be a product of choice, psychopathology beyond volitional control, or perhaps both. Clinical skills alone typically are not sufficient for diagnosing or detecting malingering. Medical education needs to provide doctors with the conceptual, developmental, and management frameworks to understand and manage patients whose symptoms appear to be simulated. Central to understanding factitious disorders and malingering are the explanatory models and beliefs used to provide meaning for both patients and doctors.7

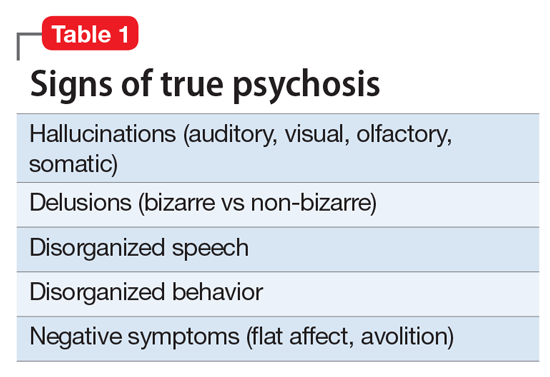

When considering malingered psychosis, the suspecting physician must stay alert to possible motives. Also, the patient’s presentation might provide some clues when there is marked variability, such as discrepancies in the history, gross inconsistencies, or blatant contradictions. Hallucinations are a heterogeneous experience, and discerning between true vs feigned symptoms can be challenging for even the seasoned clinician. It can be helpful to study the phenomenology of typical vs atypical hallucinatory symptoms.8 Examples of atypical symptoms include:

- vague hallucinations

- experiencing hallucinations of only 1 sensory modality (such as voices alone, visual images in black and white only)

- delusions that have an abrupt onset

- bizarre content without disordered thinking.2,6,9,10