Should I order an anti-CCP antibody test to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis?

Yes. Testing for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis (RA) because it is a highly specific test.

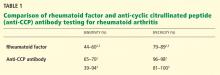

For many years, the diagnosis of RA has been based on the presentation of symmetrical small- and large-joint polyarthritis that spares the lower spine, further supported by the presence of characteristic joint damage on radiography and an elevated rheumatoid factor while also excluding clinical mimics. However, rheumatoid factor is often not detected early in RA, and detection of rheumatoid factor is not specific for RA. Testing for anti-CCP antibody can provide additional information and, in some cases, enable earlier and more specific diagnosis.

An important advance in our understanding of the pathogenesis of RA and in improving our ability to diagnose it early is the recognition that RA patients often produce autoantibodies directed against proteins and peptides containing the amino acid citrulline. Citrulline is generated in an inflammatory environment by the modification of the amino acid arginine by the enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase. Antibodies against cyclic citrulline are generated by patients with a certain genetic makeup, although citrulline can be detected in inflammatory tissues in conditions other than RA (without the antibody).

Anti-CCP antibody has been found in sera up to 10 years before the onset of joint symptoms in patients who later develop RA and may appear somewhat earlier than rheumatoid factor.1 From 10% to 15% of RA patients remain seronegative for rheumatoid factor throughout the disease course.

INFORMAL GUIDELINES FOR ANTI-CCP ANTIBODY TESTING

The role of anti-CCP antibody testing in the management of RA is still being defined, but we suggest several informal guidelines.

Anti-CCP antibody testing can help interpret the significance of an inexplicably high rheumatoid factor titer in the absence of classic RA. In such situations, a negative anti-CCP antibody test suggests a nonrheumatic disorder such as hepatitis C virus infection or endocarditis, whereas a positive anti-CCP antibody test is more consistent with early or even preclinical RA since this test, unlike rheumatoid factor testing, is generally negative in the setting of infection.

However, in a patient who has documented RA and who is seropositive for rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP antibody testing has limited value, as the information it provides may be redundant. In a patient with a low to intermediate probability for RA and with a negative or low level of rheumatoid factor, a positive anti-CCP antibody test helps confirm the diagnosis. Rheumatoid factor positivity and anti-CCP antibody positivity are each associated with more severe RA. Neither test varies with the activity of RA.

Finally, in smokers with a particular genotype, the presence of anti-CCP antibody predicts a particularly worse course for RA.

THE ROLE OF RHEUMATOID FACTOR TESTING

Rheumatoid factor, first described in 1940,4 is an antibody against the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G. The cutoff value for positivity varies by laboratory but is usually greater than 45 IU/mL by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or laser nephelometry, or greater than 1:80 by latex fixation. However, serum titers or serum levels expressed as “IU/mL” cannot accurately be compared between laboratories; instead, when using tests for rheumatoid factor, physicians should refer to specificity and sensitivity measurements for each analyzing laboratory.

Around 50% of patients with RA become positive for rheumatoid factor in the first 6 months, and 85% become positive over the first 2 years. Also, rheumatoid factor testing suffers from low specificity, since it can be detected (although sometimes in low levels) in a variety of infectious and inflammatory conditions, such as bacterial endocarditis, malaria, tuberculosis, osteomyelitis, hepatitis C (with or without cryoglobulinemia), Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary biliary cirrhosis, postvaccination arthropathy, and aging.

Current detection methods cannot differentiate between naturally occurring, transiently induced, and RA-associated rheumatoid factor. The levels are generally higher in RA than in many non-RA disorders, but significant overlap occurs. Rheumatoid factor positivity serves as a marker of poor prognosis, predicting generally more aggressive, erosive disease, and it is correlated with extra-articular manifestations such as rheumatoid nodules and lung involvement.

The classification criteria for RA published in 2010 by the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism provide references for the measurement of rheumatoid factor: “low-level positive” refers to values less than or equal to three times the upper limit of normal for a particular laboratory; “high-level positive” refers to values more than three times the upper limit of normal.5 This is an attempt to provide a clinically useful benchmark for the measurement of rheumatoid factor, the values of which may vary between laboratories.