Reverse T3 or perverse T3? Still puzzling after 40 years

Four decades after reverse T3 (3,3´5´-triiodothyronine) was discovered, its physiologic and clinical relevance remains unclear and is still being studied. But scientific uncertainty has not stopped writers in the consumer press and on the Internet from making unsubstantiated claims about this hormone. Many patients believe their hypothyroid symptoms are due to high levels of reverse T3 and want to be tested for it, and some even bring in test results from independent laboratories.

HOW THYROID HORMONES WERE DISCOVERED

In 1970, Braverman et al9 showed that T4 is converted to T3 in athyreotic humans, and Sterling et al10 demonstrated the same in healthy humans. During that decade, techniques for measuring T4 were refined,11 and a specific radioimmunoassay for reverse T3 allowed a glimpse of its physiologic role.12 In 1975, Chopra et al13 noted reciprocal changes in the levels of T3 and reverse T3 in systemic illnesses—ie, when people are sick, their T3 levels go down and their reverse T3 levels go up.

The end of the 70s was marked by a surge of interest in T4 metabolites, including the development of a radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-diiodothyronine (3-3´ T2).18

The observed reciprocal changes in serum levels of T3 and reverse T3 suggested that T4 degradation is regulated into activating (T3) or inactivating (reverse T3) pathways, and that these changes are a presumed homeostatic process of energy conservation.19

HOW THYROID HORMONES ARE METABOLIZED

In the thyroid gland, for thyroid hormones to be synthesized, iodide must be oxidized and incorporated into the precursors 3-monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and 3,5-diiodotyrosine (DIT). This process is mediated by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.20

The thyroid can make T4 and some T3

T4 is the main iodothyronine produced by the thyroid gland, at a rate of 80 to 100 µg per day.21 It is synthesized from the fusion of 2 DIT molecules.

The thyroid can also make T3 by fusing 1 DIT and 1 MIT molecule, but this process accounts for no more than 20% of the circulating T3 in humans. The rest of T3, and 95% to 98% of all reverse T3, is derived from peripheral conversion of T4 through deiodination.

T4 is converted to T3 or reverse T3

The metabolic transformation of thyroid hormones in peripheral tissues determines their biologic potency and regulates their biologic effects.

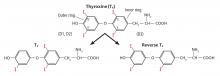

The number 4 in T4 means it has 4 iodine atoms. It can lose 1 of them, yielding either T3 or reverse T3, depending on which iodine atom it loses (Figure 3). Loss of iodine from the five-prime (5´) position on its outer ring yields T3, the most potent thyroid hormone, produced at a rate of 30 to 40 µg per day.21 On the other hand, when T4 loses an iodine atom from the five (5) position on its inner ring it yields reverse T3, produced at a rate slightly less than that of T3, 28 to 40 µg per day.21 Reverse T3 is inactive.

Both T3 and reverse T3 can shed more iodine atoms, forming in turn various isomers of T2, T1, and ultimately T0. Other pathways for thyroid hormone metabolism include glucuronidation, sulfation, oxidative deamination, and ether bond cleavage.20–22

D1 and D2 catalyze T3, D3 catalyzes reverse T3

Three types of enzymes that mediate deiodination have been identified and designated D1, D2, and D3. In humans they are expressed in variable amounts throughout the body:

- D1 mainly in the liver, kidneys, thyroid, and pituitary, but notably absent in the central nervous system

- D2 in the central nervous system, pituitary, brown adipose tissue, thyroid, placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart

- D3 in the central nervous system, skin, hemangiomas, fetal liver, placenta, and fetal tissues.23

D1 and D2 are responsible for converting T4 to T3, and D3 is responsible for converting T4 to reverse T3.

Plasma concentrations of free T4 and free T3 are relatively constant; however, tissue concentrations of free T3 vary in different tissues according to the amount of hormone transported and the activity of local deiodinases.23 Most thyroid hormone actions are initiated after T3 binds to its nuclear receptor. In this setting, deiodinases play a critical role in maintaining tissue and cellular thyroid hormone levels, so that thyroid hormone signaling can change irrespective of serum hormonal concentrations.22–24 For example, in the central nervous system, production of T3 by local D2 is significantly relevant for T3 homeostasis.22,23

Deiodinases also modulate the tissue-specific concentrations of T3 in response to iodine deficiency and to changes in thyroid state.23 During iodine deficiency and hypothyroidism, tissues that express D2, especially brain tissues, increase the activity of this enzyme in order to increase local conversion of T4 to T3. In hyperthyroidism, D1 overexpression contributes to the relative excess of T3 production, while D3 up-regulation in the brain protects the central nervous system from excessive amounts of thyroid hormone.23