Relationship between Hospital 30-Day Mortality Rates for Heart Failure and Patterns of Early Inpatient Comfort Care

BACKGROUND: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rewards hospitals that have low 30-day risk-standardized mortality rates (RSMR) for heart failure (HF).

OBJECTIVE: To describe the use of early comfort care for patients with HF, and whether hospitals that more commonly initiate comfort care have higher 30-day mortality rates.

DESIGN: A retrospective, observational study.

SETTING: Acute care hospitals in the United States.

PATIENTS: A total of 93,920 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries admitted with HF from January 2008 to December 2014 to 272 hospitals participating in the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure registry.

EXPOSURE: Early comfort care (defined as comfort care within 48 hours of hospitalization) rate.

MEASUREMENTS: A 30-day RSMR.

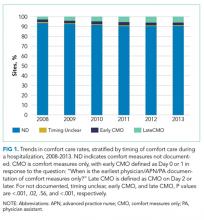

RESULTS: Hospitals’ early comfort care rates were low for patients admitted for HF, with no change over time (2.5% to 2.6%, from 2008 to 2014, P = .56). Rates varied widely (0% to 40%), with 14.3% of hospitals not initiating comfort care for any patients during the first 2 days of hospitalization. Risk-standardized early comfort care rates were not correlated with RSMR (median RSMR = 10.9%, 25th to 75th percentile = 10.1% to 12.0%; Spearman’s rank correlation = 0.13; P = .66).

CONCLUSIONS: Hospital use of early comfort care for HF varies, has not increased over time, and on average, is not correlated with 30-day RSMR. This suggests that current efforts to lower mortality rates have not had unintended consequences for hospitals that institute early comfort care more commonly than their peers.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

In an effort to improve the quality of care delivered to heart failure (HF) patients, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publish hospitals’ 30-day risk-standardized mortality rates (RSMRs) for HF.1 These mortality rates are also used by CMS to determine the financial penalties and bonuses that hospitals receive as part of the national Hospital Value-based Purchasing program.2 Whether or not these efforts effectively direct patients towards high-quality providers or motivate hospitals to provide better care, few would disagree with the overarching goal of decreasing the number of patients who die from HF.

However, for some patients with chronic disease at the end of life, goals of care may change. The quality of days lived may become more important than the quantity of days lived. As a consequence, high-quality care for some patients at the end of life is associated with withdrawing life-sustaining or life-extending therapies. Over time, this therapeutic perspective has become more common, with use of hospice care doubling from 23% to 47% between 2000 and 2012 among Medicare beneficiaries who died.3 For a national cohort of older patients admitted with HF—not just those patients who died in that same year—hospitals’ rates of referral to hospice are considerably lower, averaging 2.9% in 2010 in a national study.4 Nevertheless, it is possible that hospitals that more faithfully follow their dying patients’ wishes and withdraw life-prolonging interventions and provide comfort-focused care at the end of life might be unfairly penalized if such efforts resulted in higher mortality rates than other hospitals.

Therefore, we used Medicare data linked to a national HF registry with information about end-of-life care, to address 3 questions: (1) How much do hospitals vary in their rates of early comfort care and how has this changed over time; (2) What hospital and patient factors are associated with higher early comfort care rates; and (3) Is there a correlation between 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rates for HF with hospital rates of early comfort care?

METHODS

Data Sources

We used data from the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry. GWTG-HF is a voluntary, inpatient, quality improvement registry5-7 that uses web-based tools and standard questionnaires to collect data on patients with HF admitted to participating hospitals nationwide. The data include information from admission (eg, sociodemographic characteristics, symptoms, medical history, and initial laboratory and test results), the inpatient stay (eg, therapies), and discharge (eg, discharge destination, whether and when comfort care was initiated). We linked the GWTG-HF registry data to Medicare claims data in order to obtain information about Medicare eligibility and patient comorbidities. Additionally, we used data from the American Hospital Association (2008) for hospital characteristics. Quintiles Real-World & Late Phase Research (Cambridge, MA) serves as the data coordinating center for GWTG-HF and the Duke Clinical Research Institute (Durham, NC) serves as the statistical analytic center. GWTG-HF participating sites have a waiver of informed consent because the data are de-identified and primarily used for quality improvement. All analyses performed on this data have been approved by the Duke Medical Center Institutional Review Board.