Is Posthospital Syndrome a Result of Hospitalization-Induced Allostatic Overload?

After discharge from the hospital, patients face a transient period of generalized susceptibility to disease as well as an elevated risk for adverse events, including hospital readmission and death. The term posthospital syndrome (PHS) has been used to describe this time of enhanced vulnerability. Based on data from bench to bedside, this narrative review examines the hypothesis that hospital-related allostatic overload is a plausible etiology of PHS. Resulting from extended exposure to stress, allostatic overload is a maladaptive state driven by overuse and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system that ultimately generates pathophysiologic consequences to multiple organ systems. Markers of allostatic overload, including elevated levels of cortisol, catecholamines, and inflammatory markers, have been associated with adverse outcomes after hospital discharge. Based on the evidence, we suggest a possible mechanism for postdischarge vulnerability, encourage critical contemplation of traditional hospital environments, and suggest interventions that might improve outcomes.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

After discharge from the hospital, patients have a significantly elevated risk for adverse events, including emergency department use, hospital readmission, and death. More than 1 in 3 patients discharged from the hospital require acute care in the month after hospital discharge, and more than 1 in 6 require readmission, with readmission diagnoses frequently differing from those of the preceding hospitalization.1-4 This heightened susceptibility to adverse events persists beyond 30 days but levels off by 7 weeks after discharge, suggesting that the period of increased risk is transient and dynamic.5

The term posthospital syndrome (PHS) describes this period of vulnerability to major adverse events following hospitalization.6 In addition to increased risk for readmission and mortality, patients in this period often show evidence of generalized dysfunction with new cognitive impairment, mobility disability, or functional decline.7-12 To date, the etiology of this vulnerability is neither well understood nor effectively addressed by transitional care interventions.13

One hypothesis to explain PHS is that stressors associated with the experience of hospitalization contribute to transient multisystem dysfunction that induces susceptibility to a broad range of medical maladies. These stressors include frequent sleep disruption, noxious sounds, painful stimuli, mobility restrictions, and poor nutrition.12 The stress hypothesis as a cause of PHS is therefore based, in large part, on evidence about allostasis and the deleterious effects of allostatic overload.

Allostasis defines a system functioning within normal stress-response parameters to promote adaptation and survival.14 In allostasis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) exist in homeostatic balance and respond to environmental stimuli within a range of healthy physiologic parameters. The hallmark of a system in allostasis is the ability to rapidly activate, then successfully deactivate, a stress response once the stressor (ie, threat) has resolved.14,15 To promote survival and potentiate “fight or flight” mechanisms, an appropriate stress response necessarily impacts multiple physiologic systems that result in hemodynamic augmentation and gluconeogenesis to support the anticipated action of large muscle groups, heightened vigilance and memory capabilities to improve rapid decision-making, and enhancement of innate and adaptive immune capabilities to prepare for wound repair and infection defense.14-16 The stress response is subsequently terminated by negative feedback mechanisms of glucocorticoids as well as a shift of the ANS from sympathetic to parasympathetic tone.17,18

Extended or repetitive stress exposure, however, leads to dysregulation of allostatic mechanisms responsible for stress adaptation and hinders an efficient and effective stress response. After extended stress exposure, baseline (ie, resting) HPA activity resets, causing a disruption of normal diurnal cortisol rhythm and an increase in total cortisol concentration. Moreover, in response to stress, HPA and ANS system excitation becomes impaired, and negative feedback properties are undermined.14,15 This maladaptive state, known as allostatic overload, disrupts the finely tuned mechanisms that are the foundation of mind-body balance and yields pathophysiologic consequences to multiple organ systems. Downstream ramifications of allostatic overload include cognitive deterioration, cardiovascular and immune system dysfunction, and functional decline.14,15,19

Although a stress response is an expected and necessary aspect of acute illness that promotes survival, the central thesis of this work is that additional environmental and social stressors inherent in hospitalization may unnecessarily compound stress and increase the risk of HPA axis dysfunction, allostatic overload, and subsequent multisystem dysfunction, predisposing individuals to adverse outcomes after hospital discharge. Based on data from both human subjects and animal models, we present a possible pathophysiologic mechanism for the postdischarge vulnerability of PHS, encourage critical contemplation of traditional hospitalization, and suggest interventions that might improve outcomes.

POSTHOSPITAL SYNDROME

Posthospital syndrome (PHS) describes a transient period of vulnerability after hospitalization during which patients are at elevated risk for adverse events from a broad range of conditions. In support of this characterization, epidemiologic data have demonstrated high rates of adverse outcomes following hospitalization. For example, data have shown that more than 1 in 6 older adults is readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge.20 Death is also common in this first month, during which rates of postdischarge mortality may exceed initial inpatient mortality.21,22 Elevated vulnerability after hospitalization is not restricted to older adults, as readmission risk among younger patients 18 to 64 years of age may be even higher for selected conditions, such as heart failure.3,23

Vulnerability after hospitalization is broad. In patients over age 65 initially admitted for heart failure or acute myocardial infarction, only 35% and 10% of readmissions are for recurrent heart failure or reinfarction, respectively.1 Nearly half of readmissions are for noncardiovascular causes.1 Similarly, following hospitalization for pneumonia, more than 60 percent of readmissions are for nonpulmonary etiologies. Moreover, the risk for all these causes of readmission is much higher than baseline risk, indicating an extended period of lack of resilience to many types of illness.24 These patterns of broad susceptibility also extend to younger adults hospitalized with common medical conditions.3

Accumulating evidence suggests that hospitalized patients face functional decline, debility, and risk for adverse events despite resolution of the presenting illness, implying perhaps that the hospital environment itself is hazardous to patients’ health. In 1993, Creditor hypothesized that the “hazards of hospitalization,” including enforced bed-rest, sensory deprivation, social isolation, and malnutrition lead to a “cascade of dependency” in which a collection of small insults to multiple organ systems precipitates loss of function and debility despite cure or resolution of presenting illness.12 Covinsky (2011) later defined hospitalization-associated disability as an iatrogenic hospital-related “disorder” characterized by new impairments in abilities to perform basic activities of daily living such as bathing, feeding, toileting, dressing, transferring, and walking at the time of hospital discharge.11 Others have described a postintensive-care syndrome (PICS),25 characterized by cognitive, psychiatric, and physical impairments acquired during hospitalization for critical illness that persist postdischarge and increase the long-term risk for adverse outcomes, including elevated mortality rates,26,27 readmission rates,28 and physical disabilities.29 Similar to the “hazards of hospitalization,” PICS is thought to be related to common experiences of ICU stays, including mobility restriction, sensory deprivation, sleep disruption, sedation, malnutrition, and polypharmacy.30-33

Taken together, these data suggest that adverse health consequences attributable to hospitalization extend across the spectrum of age, presenting disease severity, and hospital treatment location. As detailed below, the PHS hypothesis is rooted in a mechanistic understanding of the role of exogenous stressors in producing physiologic dysregulation and subsequent adverse health effects across multiple organ systems.

Nature of Stress in the Hospital

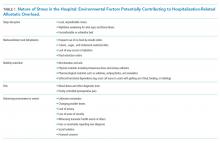

Compounding the stress of acute illness, hospitalized patients are routinely and repetitively exposed to a wide variety of environmental stressors that may have downstream adverse consequences (Table 1). In the absence of overt clinical manifestations of harm, the possible subclinical physiologic dysfunction generated by the following stress exposures may increase patients’ susceptibility to the manifestations of PHS.

Sleep Disruption

Sleep disruptions trigger potent stress responses,34,35 yet they are common occurrences during hospitalization. In surveys, about half of patients report poor sleep quality during hospitalization that persists for many months after discharge.36 In a simulated hospital setting, test subjects exposed to typical hospital sounds (paging system, machine alarms, etc.) experienced significant sleep-wake cycle abnormalities.37 Although no work has yet focused specifically on the physiologic consequences of sleep disruption and stress in hospitalized patients, in healthy humans, mild sleep disruption has clear effects on allostasis by disrupting HPA activity, raising cortisol levels, diminishing parasympathetic tone, and impairing cognitive performance.18,34,35,38,39

Malnourishment

Malnourishment in hospitalized patients is common, with one-fifth of hospitalized patients receiving nothing per mouth or clear liquid diets for more than 3 continuous days,40 and one-fifth of hospitalized elderly patients receiving less than half of their calculated nutrition requirements.41 Although the relationship between food restriction, cortisol levels, and postdischarge outcomes has not been fully explored, in healthy humans, meal anticipation, meal withdrawal (withholding an expected meal), and self-reported dietary restraint are known to generate stress responses.42,43 Furthermore, malnourishment during hospitalization is associated with increased 90-day and 1-year mortality after discharge,44 adding malnourishment to the list of plausible components of hospital-related stress.

Mobility Restriction

Physical activity counterbalances stress responses and minimizes downstream consequences of allostatic load,15 yet mobility limitations via physical and chemical restraints are common in hospitalized patients, particularly among the elderly.45-47 Many patients are tethered to devices that make ambulation hazardous, such as urinary catheters and infusion pumps. Even without physical or chemical restraints or a limited mobility order, patients may be hesitant to leave the room so as not to miss transport to a diagnostic study or an unscheduled physician’s visit. Indeed, mobility limitations of hospitalized patients increase the risk for adverse events after discharge, while interventions designed to encourage mobility are associated with improved postdischarge outcomes.47,48

Other Stressors

Other hospital-related aversive stimuli are less commonly quantified, but clearly exist. According to surveys of hospitalized patients, sources of emotional stress include social isolation; loss of autonomy and privacy; fear of serious illness; lack of control over activities of daily living; lack of clear communication between treatment team and patients; and death of a patient roommate.49,50 Furthermore, consider the physical discomfort and emotional distress of patients with urinary incontinence awaiting assistance for a diaper or bedding change or the pain of repetitive blood draws or other invasive testing. Although individualized, the subjective discomfort and emotional distress associated with these experiences undoubtedly contribute to the stress of hospitalization.