Patterns and Appropriateness of Thrombophilia Testing in an Academic Medical Center

BACKGROUND: Clinical guidelines recommend against routine use of thrombophilia testing in patients with acute thromboembolism. Thrombophilia testing rarely changes acute management of a thrombotic event.

OBJECTIVE: To determine appropriateness of thrombophilia testing in a teaching hospital.

DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: One academic medical center in Utah.

PARTICIPANTS: All patients who received thrombophilia testing between July 1, 2014, and December 31, 2014.

MAIN MEASUREMENTS: Proportion of thrombophilia tests occurring in situations associated with minimal clinical utility, defined as tests meeting at least 1 of the following criteria: discharged before results available; test type not recommended; testing in situations associated with decreased accuracy; duplicate testing; and testing following a provoked thrombotic event.

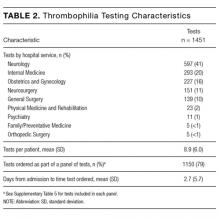

RESULTS: Overall, 163 patients received a total of 1451 thrombophilia tests for stroke (50% of tests; 35% of patients), venous thromboembolism (21% of tests; 21% of patients), and pregnancy-related conditions (15% of tests; 25% of patients). Of the 39 different test types performed, the most common were cardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies (9% each), lupus anticoagulant (9%), and β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies (8% each). In total, 911 tests (63%) were performed in situations associated with minimal clinical utility, with 126 patients (77%) receiving at least one such test. Only 2 patients (1%) had clear documentation of being offered genetic consultation.

CONCLUSIONS: Thrombophilia testing in this single-center study was often associated with minimal clinical utility. Strategies to improve testing practices (eg, hematology specialty consult prior to inpatient testing, improved order panels) might help minimize inappropriate testing and promote value-driven care.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Thrombophilia is a prothrombotic state, either acquired or inherited, leading to a thrombotic predisposition.1 The most common heritable thrombophilias include factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin G20210A. The most common acquired thrombophilia is the presence of phospholipid antibodies.1 Thrombotic risk varies with thrombophilia type. For example, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S, and the presence of phospholipid antibodies, confer higher risk than FVL and prothrombin G20210A.2-5 Other thrombophilias (eg, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, increased factor VIII activity) are relatively uncommon and/or their impact on thrombosis risk appears to be either minimal or unknown.1-6 There is little clinical evidence that testing for thrombophilia impacts subsequent thrombosis prevention.5,7,8 Multiple clinical guidelines and medical societies recommend against the routine and indiscriminate use of thrombophilia testing.8-13 In general, thrombophilia testing should be considered only if the result would lead to changes in anticoagulant initiation, intensity, and/or duration, or might inform interventions to prevent thrombosis in asymptomatic family members.8-13 However, thrombophilia testing rarely changes the acute management of a thrombotic event and may have harmful effects on patients and their family members because positive results may unnecessarily increase anxiety and negative results may provide false reassurance.6,14-18 The cost-effectiveness of thrombophilia testing is unknown. Economic models have sought to quantify cost-effectiveness, but conclusions from these studies are limited.7

The utility of thrombophilia testing in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings is further limited because patients are often treated and discharged before thrombophilia test results are available. Additionally, in these settings, multiple factors increase the risk of false-positive or false-negative results (eg, acute thrombosis, acute illness, pregnancy, and anticoagulant therapy).19,20 The purpose of this study was to systematically assess thrombophilia testing patterns in the ED and hospitalized patients at an academic medical center and to quantify the proportion of tests associated with minimal clinical utility. We hypothesize that the majority of thrombophilia tests completed in the inpatient setting are associated with minimal clinical utility.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

This study was conducted at University of Utah Health Care (UUHC) University Hospital, a 488-bed academic medical center with a level I trauma center, primary stroke center, and 50-bed ED. Laboratory services for UUHC, including thrombophilia testing, are provided by a national reference laboratory, Associated Regional and University Pathologists Laboratories. This study included patients ≥18 years of age who received thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 1) during an ED visit or inpatient admission at University Hospital between July 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014. There were no exclusion criteria. An institutional electronic data repository was used to identify patients matching inclusion criteria. All study activities were reviewed and approved by the UUHC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Outcomes

An electronic database query was used to identify patients, collect patient demographic information, and collect test characteristics. Each patient’s electronic medical record was manually reviewed to collect all other outcomes. Indication for thrombophilia testing was identified by manual review of provider notes. Thrombophilia tests occurring in situations associated with minimal clinical utility were defined as tests meeting at least one of the following criteria: patient discharged before test results were available for review; test type not recommended by published guidelines or by UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 2); test performed in situations associated with decreased accuracy; test was a duplicate test as a result of different thrombophilia panels containing identical tests; and test followed a provoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). Testing in situations associated with decreased accuracy are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 and included at least one of the following at the time of the test: anticoagulant therapy, acute thrombosis, pregnant or <8 weeks postpartum, and receiving estrogen-containing medications. Only test types known to be affected by the respective situation were included. Testing following a provoked VTE was defined as testing prompted by an acute thrombosis and performed within 3 months following major surgery (defined administratively as any surgery performed in an operating room), during pregnancy, <8 weeks postpartum, or while on estrogen-containing medications. Thrombophilia testing during anticoagulant therapy was defined as testing within 4 half-lives of anticoagulant administration based on medication administration records. Anticoagulant therapy changes were identified by comparing prior-to-admission and discharge medication lists.