The New Opioid Epidemic: Prescriptions, Synthetics, and Street Drugs

Opioid misuse, which often is the result of a prescription written for a very painful condition, has created an epidemic of opioid abuse, addiction, and fatalities across the United States. To reduce the risks from prescribed opioids, regulators and public health authorities have implemented intensive risk mitigation programs, prescription-monitoring programs, and prescribing guidelines.

Clinicians have been encouraged to manage acute and chronic pain more comprehensively. Concurrently, pharmaceutical companies have introduced tamper-resistant formulations, also known as abuse-deterrent formulations, intended to limit manipulation of the contents for insufflation or injection. Although some of these formulations have made tampering difficult, overall they have not effectively reduced inappropriate use or abuse.

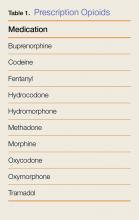

All of these interventions have resulted in a reduction in the availability of affordable, commercially available pharmaceutical opioids (Table 1). Simultaneously, other prescription opioid users have found that the analgesic or euphoric effects of their prescription opioids were no longer sufficient, due to opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. Both of these forces are driving opioid users to seek more potent opioid products and higher doses to achieve the desired psychoactive and pain-relieving effects.

For these reasons, many opioid users turned to less expensive, readily available, illicitly produced heroin and potent synthetic opioids—mainly fentanyl derivatives. The increased use of heroin and synthetic opioids has resulted in a sharp rise in overdoses and deaths, which continue to be a daily presentation in EDs throughout the country.

This review describes the emergence of the new synthetic opioids, and the steps emergency physicians (EPs) can take to identify and manage ED patients who have been exposed to these agents.

Case

A 34-year-old woman with a history of opioid-use disorder was found unresponsive by a family member who immediately called emergency medical services (EMS). Upon arrival, the emergency medical technicians noted the patient’s agonal respiration and pinpoint pupils. They immediately provided assisted ventilations via a bag-valve-mask (BVM) and administered 2 mg of intranasal naloxone prior to transport. The patient remained unresponsive, with no improvement in her respiratory status.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was still comatose, and her pupils remained pinpoint. Vital signs at presentation were: heart rate, 48 beats/min; blood pressure, 70/40 mm Hg; agonal respiration; and temperature, 98.2°F. Oxygen saturation was 86% while receiving assisted ventilation through BVM. An intravenous (IV) line was established.

What is the differential diagnosis of this toxidrome in the current era of emerging drugs of abuse?

The differential diagnosis of a patient with pinpoint pupils and respiratory depression who does not respond to naloxone typically includes overdose with gamma-hydroxybutyrate, clonidine, or the combined use of sedative-hypnotic agents with ethanol (organophosphate exposure and pontine strokes are two other causes). Naloxone administration may help diagnose opioids as a cause, and, in the past, a lack of response to naloxone was used to help exclude opioids as a cause. However, opioid poisoning should no longer be excluded from consideration in the differential diagnosis when patients are nonresponsive to naloxone. Patients who combine the use of opioids with another sedative hypnotic or who develop hypoxic encephalopathy following opioid overdose may not respond to naloxone with arousal. Most important, the emergence of ultra-potent synthetic opioid use raises the possibility that a patient may appear to be resistant to naloxone due to the extreme potency of these drugs, but may respond to extremely large doses of naloxone. These new opioids pose a grave public health threat and have already resulted in hundreds, if not thousands, of deaths.1

What are novel synthetic opioids?

Unlike heroin, which requires harvesting of plant-derived opium, the novel synthetic opioids are synthesized in laboratories, primarily in China, and shipped to the United States through commercial channels (eg, US Postal Service).2,3 Over the past few years, novel synthetic opioids have been supplementing or replacing heroin sold on the illicit market.1 Most of these novel synthetic opioids are fentanyl analogs (Table 2) that are purchased in bulk on the “Darknet”—an area hidden deep in the Internet (not discoverable by the common major search engines) that allows users to engage in questionable, even illegal, activities utilizing nontraceable currencies such as Bitcoin.4