Magnitude of Potentially Inappropriate Thrombophilia Testing in the Inpatient Hospital Setting

Laboratory costs of thrombophilia testing exceed an estimated $650 million (in US dollars) annually. Quantifying the prevalence and financial impact of potentially inappropriate testing in the inpatient hospital setting represents an integral component of the effort to reduce healthcare expenditures. We conducted a retrospective analysis of our electronic medical record to evaluate 2 years’ worth of inpatient thrombophilia testing measured against preformulated appropriateness criteria. Cost data were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2016 Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule. Of the 1817 orders analyzed, 777 (42.7%) were potentially inappropriate, with an associated cost of $40,422. The tests most frequently inappropriately ordered were Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, protein C and S activity levels, antithrombin activity levels, and the lupus anticoagulant. Potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing is common and costly. These data demonstrate a need for institution-wide changes in order to reduce unnecessary expenditures and improve patient care.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects more than 1 million patients and costs the US healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.1 Inherited and acquired thrombophilias have been perceived as important risk factors in assessing the risk of VTE recurrence and guiding the duration of anticoagulation.

Thrombophilias increase the risk of a first thrombotic event, but existing data have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of routine thrombophilia screening on subsequent management.2,3 Moreover, thrombophilia testing ordered in the context of an inpatient hospitalization is limited by confounding factors, especially during an acute thrombotic event or in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.4

Recognizing the costliness of routine thrombophilia testing, The American Society of Hematology introduced its Choosing Wisely campaign in 2013 in an effort to reduce test ordering in the setting of provoked VTEs with a major transient risk factor.5 In order to define current practice behavior at our institution, we conducted a retrospective study to determine the magnitude and financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of thrombophilia testing across all inpatient services at a large, quaternary-care academic institution over a 2-year period. Electronic medical record data containing all thrombophilia tests ordered on inpatients from June 2013 to June 2015 were obtained. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Inclusion criteria included any inpatient for which thrombophilia testing occurred. Patients were excluded if testing was ordered in the absence of VTE or arterial thrombosis or if it was ordered as part of a work-up for another medical condition (see Supplementary Material).

Thrombophilia testing was defined as any of the following: inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210 gene mutations, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity levels) or acquired thrombophilias (lupus anticoagulant [Testing refers to the activated partial thromboplastin time lupus assay.], beta-2 glycoprotein 1 immunoglobulins M and G, anticardiolipin immunoglobulins M and G, dilute Russell’s viper venom time, or JAK2 V617F mutations).

Extracted data included patient age, sex, type of thrombophilia test ordered, ordering primary service, admission diagnosis, and objective confirmation of thrombotic events. The indication for test ordering was determined via medical record review of the patient’s corresponding hospitalization. Each test was evaluated in the context of the patient’s presenting history, hospital course, active medications, accompanying laboratory and radiographic studies, and consultant recommendations to arrive at a conclusion regarding both the test’s reason for ordering and whether its indication was “inappropriate,” “appropriate,” or “equivocal.” Cost data were obtained through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule for 2016 (see Supplementary Material).6

The criteria for defining test appropriateness were formulated by utilizing a combination of major society guidelines and literature review.5,7-10 The criteria placed emphasis upon the ordered tests’ clinical relevance and reliability and were subsequently reviewed by a senior hematologist with specific expertise in thrombosis (see Supplementary Material).

Two internal medicine resident physician data reviewers independently evaluated the ordered tests. To ensure consistency between reviewers, a sample of identical test orders was compared for concordance, and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated. For purposes of analysis, equivocal orders were included under the appropriate category, as this study focused on the quantification of potentially inappropriate ordering practices. Pearson chi-square testing was performed in order to compare ordering practices between services using Stata.11

RESULTS

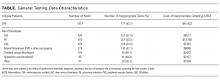

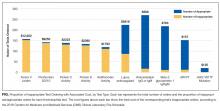

In total, we reviewed 2179 individual tests, of which 362 (16.6%) were excluded. The remaining 1817 tests involved 299 patients across 26 primary specialties. Fifty-two (2.9% of orders) were ultimately deemed equivocal. The Table illustrates the overall proportion and cost of inappropriate test ordering as well as testing characteristics of the most commonly encountered thrombotic diagnoses. The Figure illustrates the proportion of potentially inappropriate test ordering with its associated cost by test type.

Orders for Factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210, and protein C and S activity levels were most commonly deemed inappropriate due to the test results’ failure to alter clinical management (97.3%, 99.2%, 99.4% of their inappropriate orders, respectively). Antithrombin testing (59.4%) was deemed inappropriate most commonly in the setting of acute thrombosis. The lupus anticoagulant (82.8%) was inappropriately ordered most frequently in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.

Ordering practices were then compared between nonteaching and teaching inpatient general medicine services. We observed a higher proportion of inappropriate tests ordered by the nonteaching services as compared to the teaching services (120 of 173 orders [69.4%] versus 125 of 320 [39.1%], respectively; P < 0.001).

The interreviewer kappa coefficient was 0.82 (P < 0.0001).