Imaging for Nonarthritic Hip Pathology

Diagnostic imaging is an essential aspect of the work-up for nonarthritic hip pain. This review, a comprehensive summary of orthopedic diagnostic imaging for nonarthritic hip pathology, includes the modalities of radiographs, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. The use of each modality in the work-up for nonarthritic hip pain is discussed.

Take-Home Points

- Be sure to have a well centered AP pelvis without rotation.

- Get at least 3 plain radiographs—AP pelvis, false profile, and lateral hip view.

- Ensure that there is sufficient acetabular coverage, LCEA >20° on AP pelvis and ACEA >20° on false profile view.

- CT scans are helpful for precise hip pathomorphology but must be weighed against risk of radiation exposure.

- MRI or MRA can be helpful to diagnose intra-articular as well as extra-articular hip and pelvis abnormalities.

In the work-up for nonarthritic hip pain, the value of diagnostic imaging is in objective findings, which can support or weaken the leading diagnoses based on subjective complaints, recalled history, and, in some cases, elusive physical examination findings. Morphologic changes alone, however, do not always indicate pathology.1,2 At presentation and at each step in the work-up, it is imperative to evaluate the entire clinical picture. The prudent clinician uses both clinical and radiographic findings to make the diagnosis and direct treatment.

Radiography

The first step in diagnostic imaging is radiography. Although use of plain radiographs is routine, their value cannot be understated. Standard hip radiographs—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and frog-leg (cross-table lateral) radiographs of the hip—provide a wealth of information.3-6

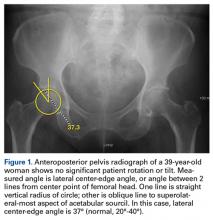

Evaluated first is the radiograph itself. For example, the ideal AP radiograph of the pelvis (Figure 1) is centered on the lower sacrum, and the patient is not rotated.

AP radiographs allow for evaluation of fractures, intraosseous sclerosis, acetabular depth, inclination and version, acetabular overcoverage, joint-space narrowing, femoroacetabular congruency, femoral head sphericity, and femoral head–neck offset.7,8,10 Inspection for labral calcification is important, as it can indicate repetitive damage at the extremes of range of motion.

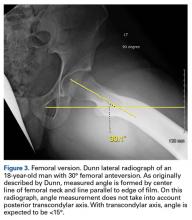

On AP pelvis radiographs, it is important to distinguish coxa profunda from acetabular protrusion. These entities are on the same pathomorphologic spectrum and are similar but distinctively different. Coxa profunda refers to the depth of the acetabulum relative to the ilioischial line, and acetabular protrusion refers to the depth (or medial position) of the femoral head relative to the ilioischial line. Each condition suggests—but is not diagnostic for—pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).11Acetabular rotation is another important entity that can be evaluated on well-centered, nontilted AP pelvic radiographs. Acetabular rotation refers to the opening direction of the acetabulum. It may be anterior (anteverted), neutral, or posterior (retroverted). Anteversion is present when the anterior acetabular rim does not traverse the posterior rim shadow4; in other words, the ring formed by the acetabulum is not twisted. When the walls overlap but do not intersect, the cup has neutral version. Retroversion is qualitatively determined by the crossover (figure-of-8) and posterior wall signs12 and is associated with pincer-type FAI and the development of hip osteoarthritis.12Dunn lateral radiographs (Figure 2A), taken with 90° hip flexion, were originally used to measure femoral neck anteversion.13

False-profile radiographs (Figure 6), valuable in evaluating anterior acetabular coverage and femoral head–neck junction morphology,14,15 allow characterization of both cam-type and pincer-type FAI.

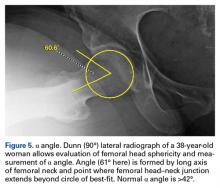

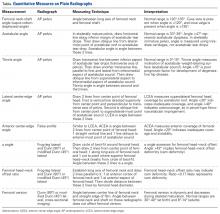

Quantitative measures warrant specific consideration (Table). Femoroacetabular morphology is quantitatively measured by α angle, Tönnis angle (acetabular inclination angle), and lateral center-edge angle (LCEA).7,8,10 The α angle (Figure 4) detects the loss of normal anterosuperior femoral head–neck junction concavity caused by a convex osseous prominence. An α angle >50° represents a cam deformity.16 In a cohort study of 338 patients, Nepple and colleagues17 qualitatively associated increased α angle with severe intra-articular hip disease. Murphy and colleagues18 found a Tönnis angle >15° to be a poor prognostic factor in untreated hip dysplasia. LCEA quantifies superolateral femoral head coverage,19 and its normal range is 20° to 40°.20 LCEA <20° indicates dysplasia of the femoroacetabular joint, and LCEA >40° indicates overcoverage and pincer-type FAI. As with any quantitative radiographic measurement, results should be interpreted within the presenting clinical context.

Radiographic findings, even findings based on these special radiographs, may underestimate the pathologic process.