How should asymptomatic hypertension be managed in the hospital?

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

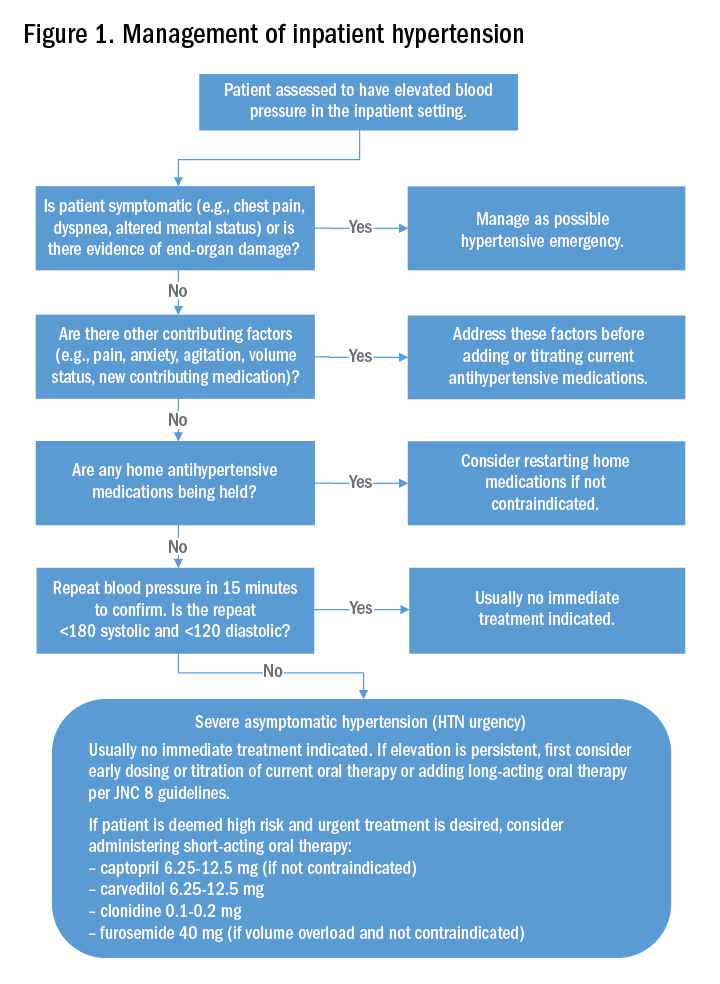

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3