Forging ahead

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 45-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with 2 days of generalized, progressive weakness. Her ability to walk and perform daily chores was increasingly limited. On the morning of her presentation, she was unable to stand up without falling.

A complaint of weakness must be classified as either functional weakness related to a systemic process or true neurologic weakness from dysfunction of the central nervous system (eg, brain, spinal cord) or peripheral nervous system (eg, anterior horn cell, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle). More information on her clinical course and a detailed neurologic exam will help clarify this key branch point.

She was 2 weeks status-post laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and gastric band removal performed in Europe. Immediately following surgery, she experienced abdominal discomfort and nausea with occasional nonbloody, nonbilious emesis, attributed to expected postoperative anatomical changes. She developed a postoperative pneumonia treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate. She tolerated her flight back to the United States, but her abdominal discomfort persisted and she had minimal oral intake due to her nausea.

Functional weakness may stem from hypovolemia from insufficient oral intake, anemia related to the recent surgery, electrolyte abnormalities, chronic nutritional issues associated with obesity and weight-reduction surgery, and pneumonia. Prolonged air travel, obesity, and recent surgery place her at risk for venous thromboembolism, which may manifest as reduced exercise tolerance. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain persisting for 2 weeks after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery raises several concerns, including gastric remnant distension (although hiccups are often prominent); stomal stenosis, which typically presents several weeks after surgery; marginal ulceration; or infection at the surgical site or from an anastomotic leak. She may also have a surgery- or medication-related myopathy.

The patient had a history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, migraine headaches, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Four years previously, she had undergone gastric banding complicated by band migration and ulceration at the banding site. Her medications were amlodipine, losartan, ranitidine, acetaminophen, and nadroparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during her flight. She denied alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use. On further questioning, she reported diaphoresis, mild dyspnea, loose stools, and a sensation of numbness and “heaviness” in her arms. Her abdominal pain was limited to the surgical incision and was controlled with acetaminophen. She denied fevers, cough, chest pain, diplopia, or dysphagia.

Heaviness in both arms could result from an acutely presenting myopathic or neuropathic process, while the coexistence of numbness suggests a sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Obesity and gastric bypass surgery increase her nutritional risk, and thiamine deficiency may present as an acute axonal polyneuropathy (ie, beriberi). Unlike vitamin B12 deficiency, which may take years to develop, thiamine deficiency can present within 4 weeks of gastric bypass surgery. Her dyspnea may be a manifestation of diaphragmatic weakness, although her ostensibly treated pneumonia or as of yet unproven postoperative anemia may be contributing. Chemoprophylaxis mitigates her risk of venous thromboembolism, which is, nonetheless, unlikely to account for the gastrointestinal symptoms and upper extremity weakness. If she is continuing to take amlodipine and losartan but has become volume-depleted, hypotension may be contributing to the generalized weakness.

Physical examination revealed an obese, pale and diaphoretic woman. Her temperature was 36.9°C, heart rate 77 beats per minute, blood pressure 158/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 28 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 99% on ambient air. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy and a normal thyroid exam. There were no murmurs on cardiac examination, and jugular venous pressure was estimated at 10 cm of water. Her lung sounds were clear. Her abdomen was soft, nondistended, with localized tenderness and fluctuance around the midline surgical incision with a small amount of purulent drainage. She was alert and oriented to name, date, place, and situation. Cranial nerves II through XII were grossly intact. Strength was 4/5 in bilateral biceps, triceps and distal hand and finger extensors, 3/5 in bilateral deltoids. Strength in hip flexors was 4/5 and it was 5/5 in distal lower extremities. Sensation was intact to pinprick in upper and lower extremities. Biceps reflexes were absent; patellar and ankle reflexes were 1+ and symmetric. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

The patient has symmetric proximal muscle weakness with upper extremity predominance and preserved strength in her distal lower extremities. A myopathy could explain this pattern of weakness, further substantiated by absent reflexes and reportedly intact sensation. Subacute causes of myopathy include hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, toxic myopathies from medications, or infection-induced rhabdomyolysis. However, she does not report muscle pain, and the loss of reflexes is faster than would be expected with a myopathy. A more thorough sensory examination would inform the assessment of potential neuropathic processes. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is possible; it most commonly presents as an ascending, distally predominant acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), although her upper extremity weakness predominates and there are no clear sensory changes. It remains to be determined how her wound infection might relate to her overall presentation.

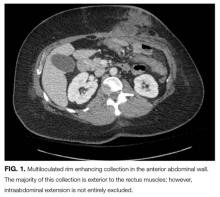

Her white blood cell count was 12,600/μL (reference range: 3,400-10,000/μL), hemoglobin was 10.2 g/dL, and platelet count was 698,000/μL. Mean corpuscular volume was 86 fL. Serum chemistries were: sodium 138 mEq/L, potassium 3.8 mEq/L, chloride 106 mmol/L, bicarbonate 15 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 5 mg/dL, creatinine 0.65 mg/dL, glucose 125 mg/dL, calcium 8.3 mg/dL, magnesium 1.9 mg/dL, phosphorous 2.4 mg/dL, and lactate 1.8 mmol/L (normal: < 2.0 mmol/L). Creatinine kinase (CK), liver function tests, and coagulation panel were normal. Total protein was 6.4 g/dL, and albumin was 2.7 g/dL. Venous blood gas was: pH 7.39 and PCO2 25 mmHg. Urinalysis revealed ketones. Blood and wound cultures were sent for evaluation. A chest x-ray was unremarkable. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a multiloculated rim-enhancing fluid collection in the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1).

She does not have any notable electrolyte derangements that would account for her weakness, and the normal creatinine kinase lowers the probability of a myopathy and excludes rhabdomyolysis. Progression of weakness from proximal to distal muscles in a symmetric fashion is consistent with botulism, and she has an intra-abdominal wound infection that could be harboring Clostridium botulinum. Nonetheless, the normal cranial nerve exam and the rarity of botulism occurring with surgical wounds argue against this diagnosis. She should receive intravenous (IV) thiamine for the possibility of beriberi. A lumbar puncture should be performed to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation, which can be seen in patients with GBS.

The patient received high-dose IV thiamine, IV vancomycin, IV piperacillin-tazobactam, and acetaminophen. Over the subsequent 4 hours, her anion gap acidosis worsened. She declined arterial puncture. Repeat venous blood gas was: pH 7.22, PCO2 28 mmHg, and bicarbonate 11 mmol/L. Lactate and glucose were normal. Serum osmolarity was 292 mmol/kg (reference range: 283-301 mmol/kg). She was started on an IV sodium bicarbonate infusion without improvement in her acidemia.

An acute anion gap metabolic acidosis suggests a limited differential diagnosis that includes lactic acidosis, D-lactic acidosis, severe starvation ketoacidosis, acute renal failure, salicylate, or other drug or poison ingestion. Starvation ketoacidosis may be contributing, but a bicarbonate value this low would be unusual. There is no history of alcohol use or other ingestions, and the normal serum osmolality and low osmolal gap (less than 10 mOsm/kg) argue against a poisoning with ethanol, ethylene glycol, or methanol. The initial combined anion gap metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis is consistent with salicylate toxicity, but she does not report aspirin ingestion. Acetaminophen use in the setting of malnutrition or starvation physiology raises the possibility of 5-oxoproline accumulation.