The Basement Flight

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A 14-year-old girl with a history of asthma presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with three months of persistent, nonproductive cough, and progressive shortness of breath. She reported fatigue, chest tightness, orthopnea, and dyspnea with exertion. She denied fever, rhinorrhea, congestion, hemoptysis, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Her age and past medical history of asthma are incongruent with her new symptoms, as asthma is typified by intermittent exacerbations, not progressive symptoms. Thus, another process, in addition to asthma, is most likely present; it is also important to question the accuracy of previous diagnoses in light of new information. Her symptoms may signify an underlying cardiopulmonary process, such as infiltrative diseases (eg, lymphoma or sarcoidosis), atypical infections, genetic conditions (eg, variant cystic fibrosis), autoimmune conditions, or cardiomyopathy. A detailed symptom history, family history, and careful physical examination will help expand and then refine the differential diagnosis. At this stage, typical infections are less likely.

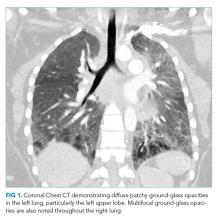

She had presented two months prior with nonproductive cough and dyspnea. At that presentation, her temperature was 36.3°C, heart rate 110 beats per minute, blood pressure 119/63 mm Hg, respiratory rate 43 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% while breathing ambient air. A chest CT with contrast demonstrated diffuse patchy multifocal ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs as well as a mixture of atelectasis and lobular emphysema in the dependent lobes bilaterally (Figure 1). Her main pulmonary artery was dilated at 3.6 cm (mean of 2.42 cm with SD 0.22). She was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia. She was administered azithromycin, weaned off oxygen, and discharged after a seven-day hospitalization.

Two months prior, she had marked tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia, and imaging revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities. The differential diagnosis for this constellation of symptoms is extensive and includes many conditions that have an inflammatory component, such as atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia pneumoniae or a common respiratory virus such as rhinovirus or human metapneumovirus. However, two findings make an acute pneumonia unlikely to be the sole cause of her symptoms: underlying emphysema and an enlarged pulmonary artery. Emphysema is an uncommon finding in children and can be related to congenital or acquired causes; congenital lobar emphysema most often presents earlier in life and is focal, not diffuse. Alpha-1-anti-trypin deficiency and mutations in connective tissue genes such as those encoding for elastin and fibrillin can lead to pulmonary disease. While not diagnostic of pulmonary hypertension, her dilated pulmonary artery, coupled with her history, makes pulmonary hypertension a strong possibility. While her pulmonary hypertension is most likely secondary to chronic lung disease based on the emphysematous changes on CT, it could still be related to a cardiac etiology.

The patient had a history of seasonal allergies and well-controlled asthma. She was hospitalized at age six for an asthma exacerbation associated with a respiratory infection. She was discharged with an albuterol inhaler, but seldom used it. Her parents denied any regular coughing during the day or night. She was morbidly obese. Her tonsils and adenoids were removed to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) at age seven, and a subsequent polysomnography was normal. Her medications included intranasal fluticasone propionate and oral iron supplementation. She had no known allergies or recent travels. She had never smoked. She had two pet cats and a dog. Her mother had a history of obesity, OSA, and eczema. Her father had diabetes and eczema.

The patient’s history prior to the recent few months sheds little light on the cause of her current symptoms. While it is possible that her current symptoms are related to the worsening of a process that had been present for many years which mimicked asthma, this seems implausible given the long period of time between her last asthma exacerbation and her present symptoms. Similarly, while tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy can be associated with infiltrative diseases (such as lymphoma), this is less common than the usual (and normal) disproportionate increase in size of the adenoids compared to other airway structures during growth in children.

She was admitted to the hospital. On initial examination, her temperature was 37.4°C, heart rate 125 beats per minute, blood pressure 143/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 48 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% breathing ambient air. Her BMI was 58 kg/m2. Her exam demonstrated increased work of breathing with accessory muscle use, and decreased breath sounds at the bases. There were no wheezes or crackles. Cardiovascular, abdominal, and skin exams were normal except for tachycardia. At rest, later in the hospitalization, her oxygen saturation was 97% breathing ambient air and heart rate 110 bpm. After two minutes of walking, her oxygen saturation was 77% and heart rate 132 bpm. Two minutes after resting, her oxygen saturation increased to 91%.