Albuminuria: When urine predicts kidney and cardiovascular disease

ABSTRACTAlbuminuria is common. Traditionally considered a precursor to diabetic nephropathy, it has now been directly linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes and death, independent of other risk factors. In this review, we compare the measures of albuminuria, examine the evidence linking it to renal failure, cardiovascular disease, and death, and provide recommendations for its testing and management.

KEY POINTS

- Albuminuria is best measured by the albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

- In several studies, albuminuria has been independently associated with a higher risk of death, cardiovascular events, heart failure, stroke, and progression of chronic kidney disease.

- Despite strong evidence linking albuminuria to adverse outcomes, evidence is limited in favor of routinely screening for it in the general population.

- Evaluating and managing albuminuria require understanding the limits of its clinical measures, controlling other risk factors for progression of renal disease, managing it medically, and referring to a specialist in certain situations.

“One can obtain considerable information concerning the general health by examining the urine.”

—Hippocrates (460?–355? BCE)

Chronic kidney disease is a notable public health concern because it is an important risk factor for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and death. Its prevalence1 exceeds 10% and is considerably higher in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or hypertension, which are growing in the United States.

While high levels of total protein in the urine have always been recognized as pathologic, a growing body of evidence links excretion of the protein albumin to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and most international guidelines now recommend measuring albumin specifically. Albuminuria is a predictor of declining renal function and is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, clinicians need to detect it early, manage it effectively, and reduce concurrent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Therefore, this review will focus on albuminuria. However, because the traditional standard for urinary protein measurement was total protein, and because a few guidelines still recommend measuring total protein rather than albumin, we will also briefly discuss total urinary protein.

MOST URINARY PROTEIN IS ALBUMIN

Most of the protein in the urine is albumin filtered from the plasma. Less than half of the rest is derived from the distal renal tubules (uromodulin or Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein), 2 and urine also contains a small and varying proportion of immunoglobulins, low-molecular-weight proteins, and light chains.

Normal healthy people lose less than 30 mg of albumin in the urine per day. In greater amounts, albumin is the major urinary protein in most kidney diseases. Other proteins in urine can be specific markers of less-common illnesses such as plasma cell dyscrasia, glomerulopathy, and renal tubular disease.

MEASURING PROTEINURIA AND ALBUMINURIA

Albumin is not a homogeneous molecule in urine. It undergoes changes to its molecular configuration in the presence of certain ions, peptides, hormones, and drugs, and as a result of proteolytic fragmentation both in the plasma and in renal tubules.3 Consequently, measuring urinary albumin involves a trade-off between convenience and accuracy.

A 24-hour timed urine sample has long been the gold standard for measuring albuminuria, but the collection is cumbersome and time-consuming, and the test is prone to laboratory error.

Dipstick measurements are more convenient and are better at detecting albumin than other proteins in urine, but they have low sensitivity and high interobserver variation.3–5

The albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). As the quantity of protein in the urine changes with time of day, exertion, stress level, and posture, spot-checking of urine samples is not as good as timed collection. However, a simultaneous measurement of creatinine in a spot urine sample adjusts for protein concentration, which can vary with a person’s hydration status. The ACR so obtained is consistent with the 24-hour timed collection (the gold standard) and is the recommended method of assessing albuminuria.3 An early morning urine sample is favored, as it avoids orthostatic variations and varies less in the same individual.

In a study in the general population comparing the ACR in a random sample and in an early morning sample, only 44% of those who had an ACR of 30 mg/g or higher in the random sample had one this high in the early morning sample.6 However, getting an early morning sample is not always feasible in clinical practice. If you are going to measure albuminuria, the Kidney Disease Outcomes and Quality Initiative7 suggests checking the ACR in a random sample and then, if the test is positive, following up and confirming it within 3 months with an early morning sample.

Also, since creatinine excretion differs with race, diet, and muscle mass, if the 24-hour creatinine excretion is not close to 1 g, the ACR will give an erroneous estimate of the 24-hour excretion rate.3

Table 1 compares the various methods of measuring protein in the urine.3,5,8,9 Of note, methods of measuring albumin and total protein vary considerably in their precision and accuracy, making it impossible to reliably translate values from one to the other.5

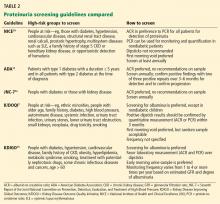

National and international guidelines (Table 2)7,10–13 agree that albuminuria should be tested in diabetic patients, as it is a surrogate marker for early diabetic nephropathy.3,13 Most guidelines also recommend measuring albuminuria by a urine ACR test as the preferred measure, even in people without diabetes.

Also, no single cutoff is universally accepted for distinguishing pathologic albuminuria from physiologic albuminuria, nor is there a universally accepted unit of measure.14 Because approximately 1 g of creatinine is lost in the urine per day, the ACR has the convenient property of numerically matching the albumin excretory rate expressed in milligrams per 24 hours. The other commonly used unit is milligrams of albumin per millimole of creatinine; 30 mg/g is roughly equal to 3 mg/mmol.

The term microalbuminuria was traditionally used to refer to albumin excretion of 30 to 299 mg per 24 hours, and macroalbuminuria to 300 mg or more per 24 hours. However, as there is no pathophysiologic basis to these thresholds (see outcomes data below), the current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines do not recommend using these terms.13,15