New-onset epilepsy in the elderly: Challenges for the internist

ABSTRACTNew-onset epilepsy in the elderly is difficult to diagnose, owing to atypical presentation, concomitant cognitive impairment, similarities with other common disorders, and nonspecific changes on electroencephalography (EEG). Its management is also challenging because of its deranging physiology, comorbidities, and polypharmacy. Antiepileptic drugs must be carefully chosen and closely monitored. Support of the patient and caregiver is key.

KEY POINTS

- About 25% of new-onset seizures occur after the age of 65.

- Most new-onset cases of epilepsy in the elderly are secondary to cerebrovascular disease, metabolic disturbances, dementia, traumatic brain injury, tumor, or drug therapy.

- The diagnosis is challenging and can be confused with syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac arrhythmia, metabolic disturbances, transient global amnesia, neurodegenerative disease, rapid-eye-movement sleep behavior disorder, and psychogenic disorders.

- The clinical presentation of seizures in the elderly differs from that in younger patients.

- A detailed clinical history, blood tests, electrocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and EEG can be helpful in diagnosing.

- No single drug is ideal for new-onset epilepsy in the elderly; the choice depends mainly on the type of seizure and the comorbidities present.

Brain tumors

Between 10% and 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly are associated with tumor, typically glioma, meningioma, and brain metastasis.28,29 Seizures are usually associated more with primary than with secondary tumors, and more with low-grade tumors than high-grade ones.30

Drug-induced

Drugs and drug withdrawal can contribute to up to 10% of acute symptomatic seizures in the geriatric population.5,8,29 The elderly are susceptible to drug-induced seizure because of a higher prevalence of polypharmacy, impaired drug clearance, and heightened sensitivity to the proconvulsant side effects of medications.1 A number of commonly used drugs have been implicated,31 including:

Antibiotics such as carbapenems and high-dose penicillin

Antihistamines such as desloratadine (Clarinex)

Pain medications such as tramadol (Ul-tram) and high-dose opiates

Neuromodulators

Antidepressants such as clomipramine (Anafranil), maprotiline (Ludiomil), amoxapine (Asendin), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).32

Seizures also follow alcohol, benzodiazepine, and barbiturate withdrawal.33

Other causes

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis is a rare cause of seizures in the elderly.34 It can present with refractory seizures, confusion, and behavioral changes with or without a known concurrent neoplastic disease.

Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome, another rare consideration, can particularly affect immunosuppressed elderly patients. This syndrome is characterized clinically by headache, confusion, seizures, vomiting, and visual disturbances with radiographic vasogenic edema.35

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The signs and symptoms of a seizure may be atypical in the elderly. Seizures more often have a picture of “epileptic amnesia,” with confusion, sleepiness, or clumsiness, rather than motor manifestations such as tonic stiffening or automatism.36,37 Postictal states are also prolonged, particularly if there is underlying brain dysfunction.38 All these features render the clinical seizure manifestations more subtle and, as such, more difficult for the uninitiated caregiver to identify.

Convulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as a single generalized seizure lasting more than 5 minutes or a series of seizures lasting longer than 30 minutes without the patient’s regaining consciousness.39 The greatest increase in the incidence of status epilepticus occurs after age 60.40 It is the first seizure in about 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly.41

Mortality rates increase with age, anoxia, and duration of status epilepticus and are over 50% in patients age 80 and older.40,42

Convulsive status epilepticus is most commonly caused by stroke.40

Absence status epilepticus can occur in elderly patients as a late complication of idiopathic generalized epilepsy related to benzodiazepine withdrawal, alcohol intoxication, or initiation of psychotropic drugs.42

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus manifests as altered mental status, psychosis, lethargy, or coma.42–44 Occasionally, it presents as a more focal cognitive disturbance with aphasia or a neglect syndrome.42,45 Electroencephalographic correlates of nonconvulsive status epilepticus include focal rhythmic discharges, often arising from frontal or temporal lobes, or generalized spike or sharp and slow-wave activity.46 Its management is challenging because of delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. The risk of death is higher in patients with severely impaired mental status or acute complications.47

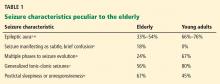

Table 1 lists the typical seizure manifestations peculiar to the elderly.37,48

Differential diagnosis of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly

New-onset epilepsy in elderly patients can be confused with syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac arrhythmia, metabolic disturbances, transient global amnesia, neurodegenerative disease, rapid-eye-movement sleep behavior disorder, psychogenic disorders, and other conditions (Table 2). If there is a high clinical suspicion of seizure, the patient should undergo electroencephalography (EEG) and be referred to a neurologist or epileptologist.

KEYS TO THE DIAGNOSIS

Clinical history

A reliable history and description of the event from an eyewitness or a video recording of the event are invaluable to the diagnosis of epileptic seizure. Signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis include aura, ictal pallor, urinary incontinence, tongue-biting, and motor symptoms, as well as postictal confusion, drowsiness, and speech disturbance.

Electroencephalography

EEG is the most useful diagnostic tool in epilepsy. However, an interictal EEG reading (ie, between epileptic attacks) in an elderly patient has limited utility, showing epileptiform activity in only about one-fourth of patients.49 Nonspecific EEG abnormalities such as intermittent focal slowing are seen in many older people even without seizure.50 Also, normal findings on outpatient EEG do not rule out epilepsy, as EEG is normal in about one-third of patients with epilepsy, irrespective of age.1,49 Activation procedures such as hyperventilation and photic stimulation add little to the diagnosis in the elderly.49

On the other hand, video-EEG monitoring is an excellent tool for evaluating possible epilepsy, as it allows accurate assessment of brain electrical activity during the events in question. Moreover, studies of video-EEG recording of seizures in elderly patients demonstrated epileptiform discharges on EEG in 76% of clinical ictal events.50

Therefore, routine EEG is a useful screening tool, and inpatient video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard to characterize events of concern and distinguish between epileptic and nonepileptic or psychogenic seizures.