Promoting higher blood pressure targets for frail older adults: A consensus guideline from Canada

ABSTRACTThe authors, who are members of the Dalhousie Academic Detailing Service and the Palliative and Therapeutic Harmonization program, recommend that antihypertensive treatment be less intense in elderly patients who are frail. This paper reviews their recommendations and the evidence behind them.

KEY POINTS

- For frail elderly patients, consider starting treatment if the systolic blood pressure is 160 mm Hg or higher.

- An appropriate target in this population is a seated systolic pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg, as long as there is no orthostatic drop to less than 140 mm Hg upon standing from a lying position and treatment does not adversely affect quality of life.

- The blood pressure target does not need to be lower if the patient has diabetes. If the patient is severely frail and has a short life expectancy, a systolic target of 160 to 190 mm Hg may be reasonable.

- If the systolic pressure is below 140 mm Hg, antihypertensive medications can be reduced as long as they are not indicated for other conditions.

- In general, one should prescribe no more than two antihypertensive medications.

REVIEWING THE LIMITED EVIDENCE

We found no studies that addressed the risks and benefits of treating hypertension in frail older adults; therefore, we concentrated on studies that enrolled individuals who were chronologically old but not frail. We reviewed prominent guidelines,9–11,32,33 the evidence base for these guidelines,34–44 and Cochrane reviews.45,46 A detailed description of the evidence used to build our recommendation can be found online.31

When we deliberated on treatment targets, we reviewed evidence from two types of randomized controlled trials47:

Drug treatment trials randomize patients to different treatments, such as placebo versus a drug or one drug compared with another drug. Patients in different treatment groups may achieve different blood pressures and clinical outcomes, and this information is then used to define optimal targets. However, it may be difficult to determine if the benefit came from lowering blood pressure or from some other effect of the drug, which can be independent of blood pressure lowering.

Treat-to-target trials randomize patients to different blood pressure goals, but the groups are treated with the same or similar drugs. Therefore, any identified benefit can be attributed to the differences in blood pressure rather than the medications used. Compared with a drug treatment trial, this type of trial provides stronger evidence about optimal targets.

We also considered the characteristics of frailty, the dilemma of polypharmacy, and the relevance of the available scientific evidence to those who are frail.

Drug treatment trials

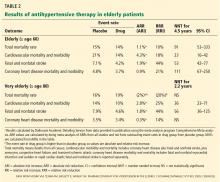

A Cochrane review45 of 15 studies with approximately 24,000 elderly participants found that treating hypertension decreased the rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as well as fatal and nonfatal stroke in the “elderly” (defined as age ≥ 60) and “very elderly” (age ≥ 80). However, in the very elderly, all-cause mortality rates were not statistically significantly different with treatment compared with placebo. The mean duration of treatment was 4.5 years in the elderly and 2.2 years in the very elderly (Table 2). Of importance, all the trials enrolled only those individuals whose systolic blood pressure was at least 160 mm Hg at baseline.

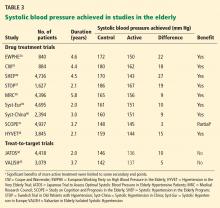

None of the studies were treat-to-target trials—patients were assigned either active medication or placebo. Thus, these trials provide evidence of benefit for treating hypertension in the elderly and very elderly but do not identify the optimal target. All of the drug treatment trials showed benefit, but none achieved a systolic pressure lower than 140 mm Hg with active treatment (Table 3). Therefore, these studies do not support a systolic target of less than 140 mm Hg in the elderly.

Treat-to-target trials: JATOS and VALISH

The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (JATOS)42 and the Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension (VALISH) study43 each enrolled more than 3,000 people age 65 or older (mean age approximately 75). Patients were randomized to either a strict systolic target of less than 140 mm Hg or a higher (more permissive) target of 140 to 160 mm Hg in JATOS and 140 to 149 mm Hg in VALISH.

In both trials, the group with strict targets achieved a systolic pressure of approximately 136 mm Hg, while the group with higher blood pressure targets achieved a systolic pressure of 146 mm Hg in JATOS and 142 mm Hg in VALISH. Despite these differences, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome.

Thus, treat-to-target studies also fail to support a systolic target of less than 140 mm Hg in the elderly, although it is important to recognize the limitations of the studies. Approximately 15% of the participants had cardiovascular disease, so the applicability of the findings to patients with target-organ damage is uncertain. In addition, there were fewer efficacy outcome events than expected, which suggests that the studies were underpowered.

When to start drug treatment

In each of the drug treatment and treat-to-target trials, the inclusion criterion for study entry was a systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg, with a mean blood pressure at entry into the drug treatment trials of 182/95 mm Hg.46 Thus, data support starting treatment if the systolic blood pressure is above 160 mm Hg, but not lower.

Notably, in all but one study,46 at least two-thirds of the participants took no more than two antihypertensive medications. Since adverse events become more common as the number of medications increases, the benefit of adding a third drug to lower blood pressure is uncertain.

Evidence in the ‘very elderly’: HYVET

With the exception of the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET),44 the mean age of elderly patients in the reported studies was between 67 and 76.

HYVET patients were age 80 and older (mean age 84) and were randomized to receive either indapamide (with or without perindopril) or placebo. The trial was stopped early at 2 years because the mortality rate was lower in the treatment group (10.1%) than in the placebo group (12.3%) (number needed to treat 46, 95% confidence interval 24–637, P = .02). There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of fatal and nonfatal stroke.

Notably, trials that are stopped early may overestimate treatment benefit.48

Evidence in frail older adults

While the above studies provide some information about managing hypertension in the elderly, the participants were generally healthy. HYVET44 specifically excluded those with a standing systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg and enrolled few patients with orthostasis (7.9% in the placebo group and 8.8% in the treatment group), a condition commonly associated with frailty. As such, these studies may be less relevant to the frail elderly, who are at higher risk of adverse drug events and have competing risks for morbidity and mortality.

Observational studies, in fact, raise questions about whether tight blood pressure control improves clinical outcomes for the very elderly. In the Leiden 85-plus study, lower systolic blood pressure was associated with lower cognitive scores, worse functional ability,49,50 and a higher mortality rate51 compared with higher systolic pressure, although it is uncertain whether these outcomes were indicative of underlying disease that could result in lower blood pressure or an effect of blood pressure-lowering.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey52 found an association between blood pressure and mortality rate that varied by walking speed. For slower walkers (based on the 6-minute walk test), higher systolic pressures were not associated with a higher risk of death, suggesting that when older adults are frail (as indicated by their slow walking speed) they are less likely to benefit from aggressive treatment of hypertension.

People at high risk because of stroke

Because the evidence is limited, it is even more difficult to judge whether lowering blood pressure below 140 mm Hg is beneficial for frail patients who have a history of stroke, compared with the possibility that medications will cause adverse effects such as weakness, orthostasis, and falls. When reviewing the evidence to answer this question, we especially looked at outcomes that affect quality of life, such as nonfatal stroke leading to disability. In contrast, because the frail elderly have competing causes of mortality, we could not assume that a mortality benefit shown in nonfrail populations could be applied to frail populations.

The PROGRESS trial (Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study)53 was in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack and a mean age of 64, who were treated with either perindopril (with or without indapamide) or placebo.

At almost 4 years, the rate of disabling stroke was 2.7% in the treatment group and 4.3% in the placebo group, a relative risk reduction of 38% and an absolute risk reduction of 1.64% (number needed to treat 61, 95% confidence interval 39–139). The relative risk reduction for all strokes (fatal and nonfatal) was similar across a range of baseline systolic pressures, but the absolute risk reduction was greater in the prespecified subgroup that had hypertension at baseline (mean blood pressure 159/94 mm Hg) than in the normotensive subgroup (mean blood pressure 136/79 mm Hg), suggesting that treatment is most beneficial for those with higher systolic blood pressures. Also, the benefit was only demonstrated in the subgroup that received two antihypertensive medications; those who received perindopril alone showed no benefit.

This study involved relatively young patients in relatively good health except for their strokes. The extent to which the results can be extrapolated to older, frail adults is uncertain because of the time needed to achieve benefit and because of the added vulnerability of frailty, which could make treatment with two antihypertensive medications riskier.

PRoFESS (Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes),54 another study in patients with previous stroke (mean age 66) showed no benefit over 2.5 years in the primary outcome of stroke using telmesartan 80 mg daily compared with placebo. This result is concordant with that of PROGRESS,53 in which patients who took only one medication did not show a significant decrease in the rate of stroke.

A possible reason for the lack of benefit from monotherapy was that the differences in blood pressure between the placebo group and the treatment group on monotherapy were small in both studies (3.8/2.0 mm Hg in PRoFESS, 5/3 mm Hg in PROGRESS). In contrast, patients on dual therapy in PROGRESS decreased their blood pressure by 12/5 mm Hg compared with placebo.