Swelling and pain 2 weeks after a dog bite

CASE CONTINUED

Our patient was started on intravenous vancomycin, clindamycin, and aztreonam for coverage of dog-mouth flora. Blood cultures and cultures of synovial fluid of the left wrist were negative. Vancomycin was discontinued after 48 hours when blood cultures did not grow staphylococcal organisms, but clindamycin and aztreonam were continued for a total of 8 days to treat possible infection with anaerobic and gram-negative enteric pathogens.

To test for autonomic dysfunction, a plastic pen case drawn lightly across each forearm revealed a loss of tactile adherence (ie, areas where moist, sweaty skin impeded the movement of the pen case) on the affected forearm, a sign of underlying nerve injury. The affected forearm was sensitive to light touch, with pain out of proportion to the stimulus.

ARRIVING AT THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the wide distribution of inflammation, autonomic dysfunction (shown by differences in temperature and sweating), radiographic evidence of demineralization, hyperesthesia, and lack of improvement in pain and swelling after two courses of antibiotics, the patient’s clinical course was determined to be consistent with complex regional pain syndrome type 1, previously referred to as reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Symptoms of complex regional pain syndrome traditionally include pain, regional edema, joint stiffness, muscular atrophy, vasomotor disturbances (causing temperature variability and erythema), regional diaphoresis, and localized skeletal demineralization on radiography.

Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 occurs as regional pain and inflammation as an excessive sympathetic reaction to an often minor insult, without nerve injury. When the syndrome occurs in a patient with obvious partial nerve injury, it is categorized as type 2 (formerly known as causalgia). The two types are clinically indistinguishable and are not uncommon. About 10% of all patients with complex regional pain syndrome have obvious nerve injury (complex regional pain syndrome type 2). In a study of 109 patients with Colles fracture, 25% developed symptoms of complex regional pain syndrome.7

Complex regional pain syndrome is difficult to diagnose, as it resembles many other ailments, such as gout, infection, bone tumor, stress fracture, and arthritis. Its pathophysiology is poorly understood, but it is believed to result from a “short circuit” in the reflex arc between somatic afferent sensory fibers and autonomic sympathetic efferent fibers, and this is thought to explain the increased sympathetic stimulation.

Although the pathophysiology is likely the same in type 1 and type 2, electromyography with a nerve conduction study is a reliable way to detect nerve damage and thus distinguish between the two types of complex regional pain syndrome.8

Our understanding of this syndrome is evolving. A recent study using sensory testing showed that 33% of patients with type 1 had combinations of increased and decreased thresholds for the detection of thermal, vibratory, and mechanical stimuli in the distribution of discrete peripheral nerves, suggesting that the patients actually had type 2.9

CONFIRMING COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME TYPE 1

3. Which of the following is the best way to confirm complex regional pain syndrome type 1?

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and complete blood cell count

- Plain radiography of the hand and forearm

- Three-phase technetium bone scan

- The Budapest diagnostic criteria

- MRI

- Autonomic testing

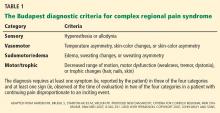

Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 is a clinical diagnosis. Diagnostic studies lack sensitivity and specificity but may confirm complex regional pain syndrome type 1 or rule out other diagnoses. The Budapest diagnostic criteria10 (Table 1) may be the best way to confirm this diagnosis. The criteria are as follows: continuing pain disproportionate to an inciting event, coupled with three of four symptoms plus at least one sign from sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor, and motor-trophic categories.

Laboratory tests are not helpful because acute-phase reactants and blood counts remain normal in these patients.

Plain radiography is not sensitive in early diagnosis, but at 2 weeks it may show patchy areas of osteopenia in adjacent bones throughout the region, as well as subsequent diffuse demineralization.

Three-phase bone scanning is more sensitive than plain radiography, with 75% of patients showing regional disparities in blood flow in early sequences and increased bone uptake in the later sequences.

MRI is a sensitive early test, as it better defines focal areas of bone loss and increased T2 bone signal in adjacent bone, as well as early soft-tissue changes. Computed tomography does not show early specific changes in muscle, tendon, or bone and so is not recommended.

THE EVALUATION CONTINUES

The admitting diagnosis was septic arthritis, and our patient underwent computed tomography, which showed focal demineralization that could have represented bone infarcts or infection, confounding the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome.

Autonomic nerve testing can help distinguish complex regional pain syndrome from other disorders. Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by increased sympathetic activity and results in increased sweat output. Autonomic testing includes resting sweat output, resting skin temperature, and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing. In one study, an increase in resting sweat output used in conjunction with quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing predicted the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome with a specificity of 98%.11 However, autonomic testing is limited to academic centers and is not readily available.

TREATING COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME TYPE 1

4. Which is the best first-line therapy for complex regional pain syndrome type 1?

- Stellate ganglion nerve block

- Occupational therapy to splint the wrist and forearm

- Oral corticosteroids

- Physical therapy to prevent loss of joint motion

- Tricyclic antidepressant drugs (eg, amitriptyline), pregabalin, and bisphosphonates

Physical therapy should be started early in all patients, with range-of-motion exercises to prevent contracture and enhance mobility.

Stellate ganglion nerve block has been used to counter severe sympathetic hyperactivity, but it also may aggravate symptoms of complex regional pain syndrome and so remains a controversial treatment.

Immobilization and splinting should be avoided, as this will augment edema, pain, and contracture of joints.

Corticosteroids do not shorten the course or assuage symptoms and may increase edema.

Amitriptyline (Elavil) and pregabalin (Lyrica) have been used successfully to counter extended courses of allodynia and hyperalgesia. Bisphosphonates may decrease bone loss and pain and may be needed should the course be complicated by myositis ossificans, a form of dystrophic bone formation in juxtaposed tendon and muscle related to neuroactivation of fibroblasts and osteoblasts.