Optimizing transitions of care to reduce rehospitalizations

ABSTRACTTransitions of care—when patients move from one health care facility to another or back home—that are poorly executed result in adverse effects for patients. Fortunately, programs can be implemented that enhance collaboration across care settings and improve outcomes including reducing hospital readmission rates.

KEY POINTS

- Traditional health care delivery models typically do not have mechanisms in place for coordinating care across settings, such as when a patient goes from the hospital to a skilled nursing facility or to home.

- Transitions can fail, leading to hospital readmission, because of ineffective patient and caregiver education, discharge summaries that are incomplete or not communicated to the patient and the next care setting, lack of follow-up with primary care providers, and poor patient social support.

- A number of programs are trying to improve transitions of care, with some showing reductions in hospital readmission rates and emergency department visits.

- Successful programs use multiple interventions simultaneously, including improved communication among health care providers, better patient and caregiver education, and coordination of social and health care services.

NO SINGLE INTERVENTION: MULTIPLE STRATEGIES NEEDED

A 2011 review found no single intervention that regularly reduced the 30-day risk of re-hospitalization.74 However, other studies have shown that multifaceted interventions can reduce 30-day readmission rates. Randomized controlled trials in short-stay, acute care hospitals indicate that improvement in the following areas can directly reduce hospital readmission rates:

- Comprehensive planning and risk assessment throughout hospitalization

- Quality of care during the initial admission

- Communication with patients, their caregivers, and their clinicians

- Patient education

- Predischarge assessment

- Coordination of care after discharge.

In randomized trials, successful programs reduced the 30-day readmission rates by 20% to 40%,54,62,75–79 and a 2011 meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found evidence that interventions associated with discharge planning helped to reduce readmission rates.80

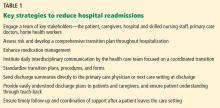

Methods developed by the national care transition models described above can help hospitals optimize patient transitions (Table 1). Although every model has its unique attributes, they have several strategies in common:

Engage a team of key stakeholders that may include patients and caregivers, hospital staff (physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, and pharmacists), community physicians (primary care, medical homes, and specialists), advance practice providers (physician assistants and nurse practitioners), and postacute care facilities and services (skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, assisted living residences, hospice, and rehabilitation facilities).

Develop a comprehensive transition plan throughout hospitalization that includes attention to factors that may affect self-care, such as health literacy, chronic conditions, medications, and social support.

Enhance medication reconciliation and management. Obtain the best possible medication history on admission, and ensure that patients understand changes in their medications, how to take each medicine correctly, and important side effects.

Institute daily interdisciplinary communication and care coordination by everyone on the health care team with an emphasis on the care plan, discharge planning, and safety issues.81

Standardize transition plans, procedures and forms. All discharging physicians should use a standard discharge summary template that includes pertinent diagnoses, active issues, a reconciled medication list with changes highlighted, results from important tests and consultations, pending test results, planned follow-up and required services, warning signs of a worsening condition, and actions needed if a problem arises.

Always send discharge summaries directly to the patient’s primary care physician or next care setting at the time of discharge.

Give the patient a discharge plan that is easy to understand. Enhance patient and family education using health literacy standards82 and interactive methods such as teach-back,83 in which patients demonstrate comprehension and skills required for self-care immediately after being taught. Such tools actively teach patients and caregivers to follow a care plan, including managing medications.

Follow up and coordinate support in a timely manner after a patient leaves the care setting. Follow-up visits should be arranged before discharge. Within 1 to 3 days after discharge, the patient should be called or visited by a case manager, social worker, nurse, or other health care provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPROVING TRANSITIONS

Although several models demonstrated significant reductions of hospital readmissions in trials, challenges remain. Studies do not identify which features of the models are necessary or sufficient, or how applicable they are to different hospital and patient characteristics. A 2012 analysis84 of a program designed to reduce readmissions in three states identified key obstacles to successfully improving care transitions:

Collaborative relationships across settings are critical, but very difficult to achieve. It takes time to develop the relationships and trust among providers, and little incentive exists for skilled nursing facilities and physicians outside the hospital to engage in the process.

Infrastructure is lacking, as is experience to implement quality improvements.

We lack proof that models work on a large scale. Confusion exists about which readmissions are preventable and which are not. More evidence is needed to help guide hospitals’ efforts to improve transitions of care and reduce readmissions.