Hepatitis C virus: Here comes all-oral treatment

ABSTRACTTreatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is evolving rapidly. The approval in 2013 of two new direct-acting antivirals—sofosbuvir (a polymerase inhibitor) and simeprevir (a second-generation protease inhibitor)—opens the door for an all-oral regimen, potentially avoiding interferon and its harsh side effects. Other direct-acting antivirals are under development.

KEY POINTS

- In clinical trials of treatment for chronic HCV infection, regimens that included a direct-acting antiviral agent were more effective than ones that did not.

- Sofosbuvir is approved in an oral dose of 400 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin for patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3, and in combination with ribavirin and interferon in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4. It is also recommended in combination with ribavirin in HCV-infected patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who are awaiting liver transplantation.

- Simeprevir is approved in an oral dose of 150 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin and interferon for patients with HCV genotype 1.

- The new drugs are expensive, a potential barrier for many patients. As more direct-acting antiviral agents become available, their cost will likely decrease.

- Combinations of direct-acting antiviral agents of different classes may prove even more effective and could eliminate the need for interferon entirely.

In late 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir and simeprevir, the newest direct-acting antiviral agents for treating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated dramatically improved treatment outcomes with these agents, opening the door to all-oral regimens or interferon-free regimens as the future standard of care for HCV.

In this article, we discuss the results of the trials that established the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and simeprevir and led to their FDA approval. We also summarize the importance of these agents and evaluate other direct-acting antivirals currently in the pipeline for HCV treatment.

HCV IS A RISING PROBLEM

Chronic HCV infection is a major clinical and public health problem, with the estimated number of people infected exceeding 170 million worldwide, including 3.2 million in the United States.1 It is a leading cause of cirrhosis, and its complications include hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Cirrhosis due to HCV remains the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States, accounting for nearly 40% of liver transplants in adults.2

The clinical impact of HCV will only continue to escalate, and in parallel, so will the cost to society. Models suggest that HCV-related deaths will double between 2010 and 2019, and considering only direct medical costs, the projected financial burden of treating HCV-related disease during this interval is estimated at between $6.5 and $13.6 billion.3

AN RNA VIRUS WITH SIX GENOTYPES

HCV, first identified in 1989, is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA flavivirus of the Hepacivirus genus measuring 50 to 60 nm in diameter.4 There are six viral genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common in the United States and traditionally the most difficult to treat.

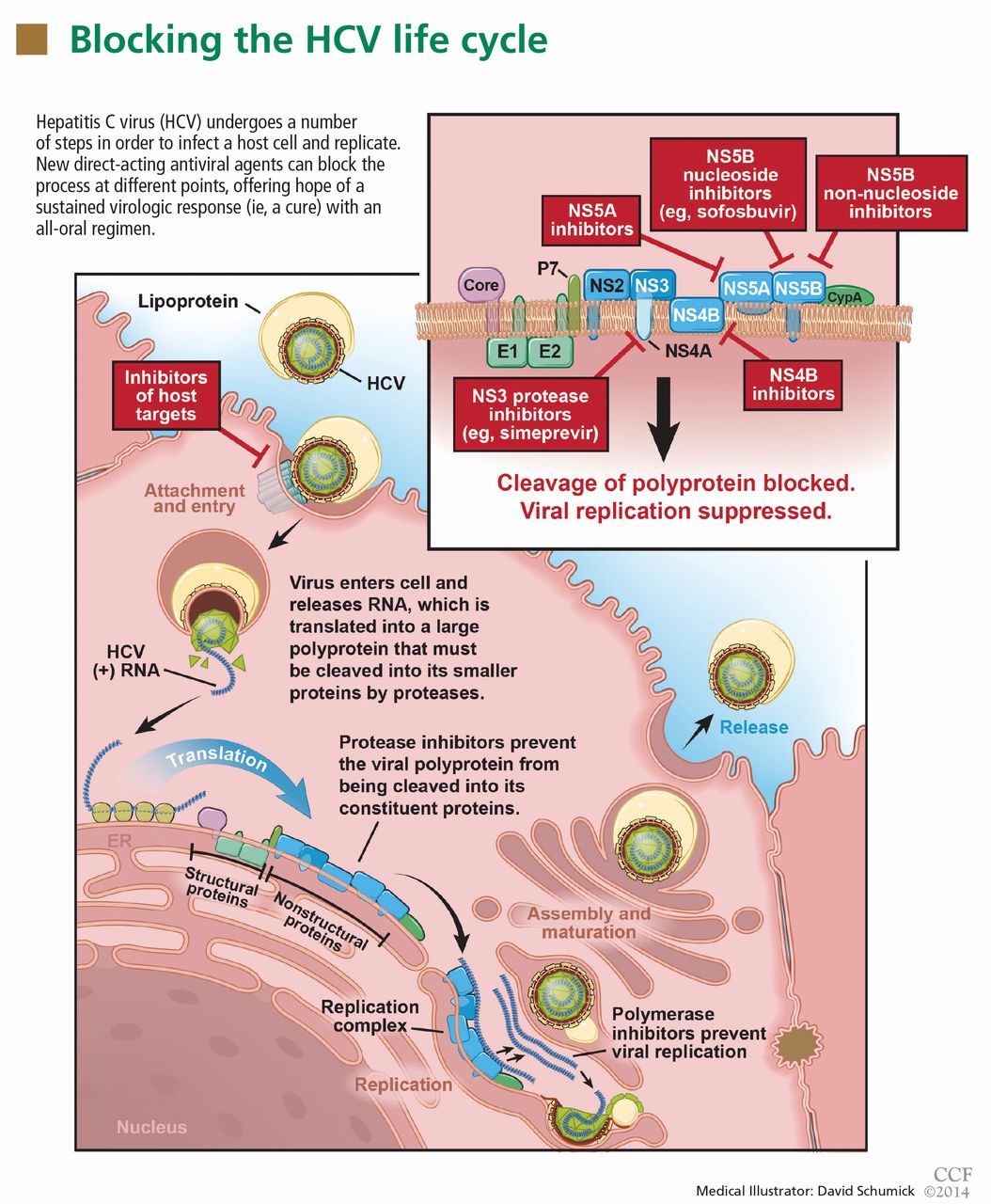

Once inside the host cell, the virus releases its RNA strand, which is translated into a single polyprotein of about 3,000 amino acids. This large molecule is then cleaved by proteases into several domains: three structural proteins (C, E1, and E2), a small protein called p7, and six nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (Figure 1).5 These nonstructural proteins enable the virus to replicate.

GOAL OF TREATING HCV: A SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

The aim of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response, defined as having no detectable viral RNA after completion of antiviral therapy. This is associated with substantially better clinical outcomes, lower rates of liver-related morbidity and all-cause mortality, and stabilization of or even improvement in liver histology.6,7 This end point has traditionally been assessed at 6 months after the end of therapy, but recent data suggest the rates at 12 weeks are essentially equivalent.

Table 1 summarizes the patterns of virologic response in treating HCV infection.

Interferon plus ribavirin: The standard of care for many years

HCV treatment has evolved over the past 20 years. Before 2011, the standard of care was a combination of interferon alfa-polyethylene glycol (peg-interferon), given as a weekly injection, and oral ribavirin. Neither drug has specific antiviral activity, and when they are used together they result in a sustained virologic response in fewer than 50% of patients with HCV genotype 1 and, at best, in 70% to 80% of patients with other genotypes.8

Nearly all patients receiving interferon experience side effects, which can be serious. Fatigue and flu-like symptoms are common, and the drug can also cause psychiatric symptoms (including depression or psychosis), weight loss, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow suppression. Ribavirin causes hemolysis and skin complications and is teratogenic.9

An important bit of information to know when using interferon is the patient’s IL28B genotype. This refers to a single-nucleotide polymorphism (C or T) on chromosome 19q13 (rs12979860) upstream of the IL28B gene encoding for interferon lambda-3. It is strongly associated with responsiveness to interferon: patients with the IL28B CC genotype have a much better chance of a sustained virologic response with interferon than do patients with CT or TT.